Direct and indirect realism

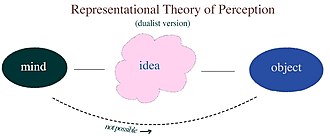

Indirect realism is broadly equivalent to the scientific view of perception that subjects do not experience the external world as it really is, but perceive it through the lens of a conceptual framework.

While there is superficial overlap, the indirect model is unlike the standpoint of idealism, which holds that only ideas are real, but there are no mind-independent objects.

Furthermore, the framework rejects the premise that knowledge arrives via a representational medium, as well as the notion that concepts are interpretations of sensory input derived from a real external world.

In On the Soul he describes how a see-er is informed of the object itself by way of the hylomorphic form carried over the intervening material continuum with which the eye is impressed.

[5] Indirect realism was popular with several early modern philosophers, including René Descartes,[6] John Locke,[6] G. W. Leibniz,[7] and David Hume.

[14] On the other hand, Gottlob Frege (in his 1892 paper "Über Sinn und Bedeutung") subscribed to indirect realism.

[21] However, epistemological dualism has come under sustained attack by other contemporary philosophers, such as Ludwig Wittgenstein (the private language argument) and Wilfrid Sellars in his seminal essay "Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind".

[27] The argument from illusion allegedly shows the need to posit sense-data as the immediate objects of perception.

[26] Naïve realism may accommodate these facts as they stand by virtue of its very vagueness (or "open-texture"): it is not specific or detailed enough to be refuted by such cases.

[27] A more developed direct realist might respond by showing that various cases of misperception, failed perception, and perceptual relativity do not make it necessary to suppose that sense-data exist.

Pressing on your eyeball with a finger creates double vision but assuming the existence of two sense-data is unnecessary: the direct realist can say that they have two eyes, each giving them a different view of the world.

Visual depth in particular is a set of inferences, not an actual experience of the space between things in a radial direction outward from the observation point.

[29] If all empirical evidence is based upon observation then the entire developed memory and knowledge of every perception and of each sense may be as skewed as the bent stick.

[26] Another potential counter-example involves vivid hallucinations: phantom elephants, for instance, might be interpreted as sense-data.

On the basis of the intractability of these questions, it has been argued that the conclusion of the argument from illusion is unacceptable or even unintelligible, even in the absence of a clear diagnosis of exactly where and how it goes wrong.

Recent work in neuroscience suggests a shared ontology for perception, imagination and dreaming, with similar areas of brain being used for all of these.

The character of experience of a physical object can be altered in major ways by changes in the conditions of perception or of the relevant sense-organs and the resulting neurophysiological processes, without change in the external physical object that initiates this process and that may seem to be depicted by the experience.

This is more of an issue now than it was for rationalist philosophers prior to Newton, such as Descartes, for whom physical processes were poorly defined.

Although Descartes' duality of natural substances may have echoes in modern physics (Bose and Fermi statistics) no agreed account of 'interpretation' has been formulated.

However, as we can scientifically verify[citation needed], this is clearly not true of the physiological components of the perceptual process.

This also brings up the problem of dualism and its relation to representative realism, concerning the incongruous marriage of the metaphysical and the physical.

Visual sensation (the argument can be extrapolated to the other senses) bears no direct resemblance to the light rays at the retina, nor to the character of what they are reflected from or pass through or what was glowing at the origin of them.

The differences at the sensory and perceptual levels between agents require that some means of ensuring at least a partial correlation can be achieved that allows the updatings involved in communication to take place.

A proponent of this theory can thus ask the direct realist why he or she thinks it is necessary to move to taking the imagining of singularity for real when there is no practical difference in the outcome in action.

Virtual constructs or no, they remain, however, selections that are causally linked to the real and can surprise us at any time—which removes any danger of solipsism in this theory.

The fundamental idea of the adverbial theory, in contrast, is that there is no need for such objects and the problems that they bring with them (such as whether they are physical or mental or somehow neither).