Retour des cendres

In a codicil to his will, written in exile at Longwood House on St Helena on 16 April 1821, Napoleon had expressed a wish to be buried "on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of the French people [whom I] loved so much".

Instead, the explanation given was that the arrival of the remains in France would undoubtedly be the cause or pretext for political unrest that the government would be wise to prevent or avoid, but that his request would be granted as soon as the situation had calmed and it was safe enough to do so.

[2][3] He also hoped to flatter the left's dreams of glory and restore the reputation of the July Monarchy (whose diplomatic relations with the rest of Europe were then under threat from its problems in Egypt, arising from its support for Muhammad Ali).

Among the rest of the royal family, the Prince de Joinville did not want to be employed on a job suitable for a "carter" or an "undertaker"; Queen Maria Amalia adjudged that such an operation would be "fodder for hot-heads"; and their daughter Louise saw it as "pure theatre".

Without doubt, it belonged to this monarchy to first rally all the powers and reconcile all the vows of the French Revolution, to fearlessly elevate and honour the statue and the tomb of a hero of the people, for there is one thing, and one only, which does not fear comparison with glory – and that is liberty!

[6] The minister then introduced a bill to authorise "funding of 1 million [francs] for translation of the Emperor Napoleon's mortal remains to the Église des Invalides and for construction of his tomb".

Speeches were made by republican critic of the Empire Glais-Bizoin, who stated that "Bonapartist ideas are one of the open wounds of our time; they represent that which is most disastrous for the emancipation of peoples, the most contrary to the independence of the human spirit."

The proposal was defended by Odilon Barrot (the future president of Napoleon III's council in 1848), whilst the hottest opponent of it was Alphonse de Lamartine, who found the measure dangerous.

The July Monarchy's official poet Casimir Delavigne wrote: On 4 or 6 June, Bertrand was received by Louis Philippe, who gave him the Emperor's arms, which were placed in the treasury.

Sire, paying homage to the memorable act of national justice which you have generously undertaken, animated by a sense of gratitude and confidence, I come to deposit in Your Majesty's hands these glorious arms, which for long I have been reduced to hiding from the light, and which I hope soon to place upon the coffin of the great Captain, on the illustrious tomb destined to hold the gaze of the Universe.

[10] Louis Philippe replied, with studied formality: In the name of France, I receive the arms of the Emperor Napoleon, which his last wishes gave to you in precious trust; they shall be guarded faithfully until the moment when I can place them on the mausoleum that national munificence is preparing for him.

I count myself happy that it has been reserved for me to return to the soil of France the mortal remains of him who added so much glory to our pomp and to pay the debt of our common Fatherland by surrounding his coffin with all the honours due to him.

[11] This ceremony angered Joseph and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the latter writing in The Times: The sword of Austerlitz must never be found in enemy hands; it must remain where it can be taken up in the day of danger for the glory of France.

The two ships finally reached Saint Helena on 8 October and in the roadstead found the French brig Oreste, commanded by Doret, who had been one of the ensigns who had come up with a daring plan at île-d'Aix to get Napoleon away on a lugger after Waterloo and who would later become a capitaine de corvette.

Doret had arrived at Saint Helena to pay his last respects to Napoleon but he also brought worrying news – the Egyptian incident, combined with Thiers' aggressive policy, were very close to causing a diplomatic rupture between France and the UK.

They then went in pilgrimage to Longwood, which was in a very ruinous state – the furniture had disappeared, many walls were covered with graffiti, Napoleon's bedroom had become a stable where a farmer pastured his beasts and got a little extra income by guiding visitors around it.

The party returned to the Valley of the Tomb at midnight on 14 October, though Joinville remained on board ship since all the operations up until the coffin's arrival at the embarkation point would be carried out by British soldiers rather than French sailors, and so he felt he could not be present at work that he could not direct.

The French section of the party was led by the Count of Rohan-Chabot and included generals Bertrand and Gourgaud, Emmanuel de Las Cases, the Emperor's old servants, Abbé Coquereau, two choirboys, captains Guyet, Charner, and Doret, Dr. Guillard (chief surgeon of the Belle-Poule), and a lead-worker, Monsieur Leroux.

Guillard slowly rolled the satin back, from the feet up: The body lay comfortably in a natural position with the head resting over a cushion while its left forearm and hand lay over his left thigh; Napoleon's face was immediately recognisable and only the sides of the nose seemed to have slightly contracted but overall, the face seemed, on the opinion of the witnesses, peaceful, and his eyes were fully closed, the eyelids even retaining most of the eyelashes; at the same time, the mouth was slightly open, showing three white incisors.

[15] All the spectators were in a state of visible shock: Gourgaud, Las Cases, Philippe de Rohan, Marchand, and all the servants wept; Bertrand barely fought his tears back.

So that all the ship's guns could be mounted, the temporary cabins set up to house the commission to Saint Helena were demolished and the dividers between them, as well as their furniture, were thrown into the sea – earning the area the nickname "Lacédémone".

This new arrangement gave rise to fresh hostile comment in the press as to the "retour des cendres": He [Guizot] who will receive the Emperor's remains is a man of the Restoration, one of the salon conspirators who allied themselves to shake the king's hand at Ghent, behind the British lines, while our old soldiers were laying down their lives to defend our territory, on the plains of Waterloo.

[21] Fearful of being overthrown thanks to the "retour" initiative (the future Napoleon III had just attempted a coup d'État) yet unable to abandon it, the government decided to rush it to a conclusion – as Victor Hugo commented, "It was pressed into finishing it.

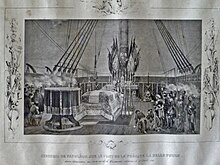

Finally 14 statues, larger than life and gilded all over, held up a vast shield on their heads, above which was placed a model of Napoleon's coffin; this whole ensemble was veiled in a long purple crêpe, sown with gold bees.

Reaching Le Havre, and then on to Val-de-la-Haye, near Rouen, where the coffin was transferred to la Dorade 3 for carrying further up the Seine, on whose banks people had gathered to pay homage to Napoleon.

In the distance could be seen slowly moving, amid steam and sunlight, upon the grey and red background of the trees of the Champs-Élysées, past tall white statues that resembled phantoms, a sort of golden mountain.

It was claimed that on Saint Helena the commission had found only an empty coffin and that the British had secretly sent the body to London for an autopsy;[34] and yet another rumour was that in 1870 the Emperor's mortal remains had been removed from the Invalides to save them from being captured in the Franco-Prussian War and had never been returned.

At its center is a massive sarcophagus which has often been described as made of red porphyry, including in the Encyclopædia Britannica as of mid-2021,[37] but is actually a purple Shoksha quartzite from a geological region near Lake Onega in Russian Karelia.

The Shoksha quartzite, intended as an echo of the porphyry used for late Roman imperial burials, was quarried in 1848 upon Nicholas I's special permission by Italian engineer Giovanni Bujatti, and shipped via Kronstadt and Le Havre to Paris, where it arrived on 10 January 1849.

It was almost finished by December 1853, but the final stages were delayed by the sudden death of Visconti that month and by Napoleon III's alternative project to move his uncle's resting place to the Basilica of Saint-Denis, which he renounced after having commissioned plans for it from Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.