Rhenish Republic

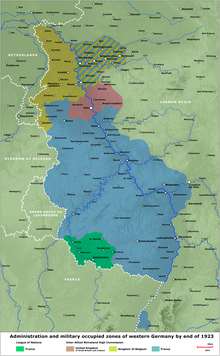

The Rhenish Republic (German: Rheinische Republik) was proclaimed at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) in October 1923 during the occupation of the Ruhr by troops from France and Belgium (January 1923 – 1925) and subjected itself to French protectorate.

The name was one applied by the short-lived separatist movement that erupted in the German Rhineland during the politically turbulent years following Germany's defeat in the First World War.

Similar political currents were stirring in the south: June 1919 had seen the proclamation by Eberhard Haaß of the "Pfälzische Republik", centred on Speyer in the occupied territory of the Bavarian Palatinate.

France, like Germany, had been profoundly traumatised by the First World War and the conduct of its occupation of the left bank of the Rhine was perceived as unsympathetic, even among its Western wartime allies.

By 1923, as the German currency collapsed, the French occupation forces headquartered at Mainz (under the command of Generals Mangin and Fayolle) were having some success in their encouragement of anti-Berlin separatism in the occupied zones.

By 1930, when French troops also vacated the left bank of the Rhine, the concept of a Rhenish Republic, independent of Berlin, no longer attracted popular support.

The Cisrhenian Republic (1797–1802) and subsequent incorporation of the region into the French Empire lasted for less than a generation, but introduced to the occupied Rhineland many of the features of the modern state.

Nonetheless, Prussia's western territories continued to adhere to the Napoleonic legal system and, in many other respects, the relationship between the citizen and the state had been permanently transformed.

In addition, mutual intolerance of religious differences, stretching back centuries, endured between Protestant Prussia and the predominantly Roman Catholic populations of the Rhineland.

On 1 February 1919, more than sixty of the Rhineland's civic leaders together with locally based Prussian National Assembly Members convened in Cologne at the invitation of the city's mayor, Konrad Adenauer of the Catholic Center Party.

Prussia was viewed by opponents as "Europe's evil spirit" and was "ruled over by an unscrupulous caste of war-fixated militaristic aristocrats" ("von einer kriegslüsternen, gewissenlosen militärischen Kaste und dem Junkertum beherrscht").

At liberty, Dorten continued his struggle: on 22 January 1922 he founded in Boppard a political party, the "Rhenish Peoples' Union" (Rheinische Volksvereinigung), chaired by Bertram Kastert (1868–1935), a senior Cologne pastor.

The Rhenish Peoples' Union stayed in the shadows, its weekly publication, German Standpoint (Deutsche Warte) and its leaders' other campaigning activities depending on French sponsorship.

[2] On 26 December 1922 the Reparations Commission determined that Germany had wilfully held back from making payments due, and two days later troops occupied the rest of the Ruhr area.

[3] With the active support of the German government, civilians in the area engaged in passive resistance and civil disobedience which largely shut down the economy of the region.

Amidst the turmoil of economic collapse, it was here that, on 15 August 1923, the "United Rhenish Movement" (die Vereinigte Rheinische Bewegung) was formed from a merging of several existing separatist groups.

Two months later, ten kilometres to the east of Aachen, the tricolour flag of the Rhenish Republic appeared outside a house in the small town of Eschweiler.

During the night of 23 October, Koblenz Castle, which had been out of the limelight since 1914 when the Kaiser had briefly established his wartime headquarters there, was captured by separatists with French military support.

On 26 October, the French High Commissioner, Paul Tirard, confirmed that the separatists were in possession of effective power (als Inhaber der tatsächlichen Macht).

Separatist leaders Dorten and Josef Friedrich Matthes interpreted Tirard's intervention as an effective carte blanche from the occupation forces.

From his occupation headquarters in Mainz, General Mangin would no doubt have had a far more richly calibrated appreciation of the possibilities presented by Rhenish separatism than the ministers in far away Paris: it is possible to infer, between the approach of the French commanders on the ground and priorities of the Poincaré government, a disparity which became impossible to overlook once Dorten launched his coup in Koblenz: at the same time Paris was coming under heavy political pressure internationally over the increasingly costly French occupation of the Ruhr.

Nearby in Brohl where two residents, Anton Brühl and Hans Feinlinger, had set up a local force to oppose the attackers, a death squad turned up and engaged in an orgy of plunder reminiscent, according to one commentator, of the Thirty Years' War.

The Siebengebirge district consists of a series of low wooded hills wedged between the A3 Autobahn and Königswinter, a resort town on the east bank of the Rhine.

On the evening of 14 November, a large number of the residents from the various small towns and villages surrounding Bad Honnef met together in an Aegidienberg guest house and resolved to resist openly the wave of looting which, they anticipated, was moving towards the southern side of the Siebengebirge area.

As they fled down the twisting road, back towards Bad Honnef, they encountered the local militia, well dug in and waiting for them: Schneider's men seized the trucks and then routed the separatist gang.

Accordingly, on 16 November, some 80 armed separatists found a gap in Schneider's defences at a hamlet called Hövel: here they seized five villagers as hostages, tied them up, and placed them in the line of fire between themselves and the now-gathering militiamen.

In order to prevent further fighting, the French installed in Aegidienberg a force of French-Moroccan soldiers for the next few weeks, while military police arrived to conduct an on-the-spot investigation.

Theodor Weinz, the separatists' hostage who had been fatally shot at Hövel, was buried in the Aegidienberg cemetery, near to its main entrance: the primary school has been named after him.

Peter Staffel, the young man who had probably been the first fatality of the Siebengebirge insurrection, is buried in the cemetery at the nearby village of Eudenbach (now incorporated within the administrative ambit of Königswinter).

Konrad Adenauer, who during the period of the "Koblenz Government" had constantly been at odds with Dorten, presented to the French generals another proposal, for the creation of a west German autonomous federal state (die Bildung eines Autonomen westdeutschen Bundesstaates).