Albanian National Awakening

Some sources attribute its origins to the revolts against centralisation in the 1830s,[1] others to the publication of the first attempt by Naum Veqilharxhi at a standardized alphabet for Albanian in 1844,[1][4][5][6] or to the collapse of the League of Prizren during the Eastern Crisis in 1881.

[12] Realising the seriousness of the situation and the danger of a general uprising, Reşid Mehmed Pasha invited the Albanian beys to a meeting on the pretext that they would be rewarded for their loyalty to the Porte.

The Bushati dynasty rule ended when an Ottoman army under Mehmed Reshid Pasha besieged the Rozafa Castle and forced Mustafa Reshiti to surrender (1831).

In their writings, the Rilindas fought to invoke feelings of love for the country by exalting patriotic traditions and episodes of history, especially that of the Skanderbeg era and folk culture; They devoted a lot of attention to native language and Albanian schools as a means to affirm individuality and national vindication.

In the ensuing years there were bursts of armed insurrections throughout Albania against the Ottoman centralising reforms, and especially against the burden of the new taxes imposed and against the obligatory military service.

Some sources attribute its origins to the revolts against centralization in the 1830s,[1] others to the publication of the first attempt by Naum Veqilharxhi at a standardized alphabet for Albanian in 1844,[1][22][23][6] or to the collapse of the League of Prizren during the Eastern Crisis in 1881.

[32] The son of one merchant family, Naum Veqilharxhi, started his work to write an alphabet intended to help Albanians overcome religious and political issues in 1824 or 1825.

[40] Austria-Hungary and the United Kingdom blocked the arrangement because it awarded Russia a predominant position in the Balkans and thereby upset the European balance of power.

[47][48] On June 10, 1878, about eighty delegates, mostly Muslim religious leaders, clan chiefs, and other influential people from the four Albanian-populated Ottoman vilayets, met in Prizren.

The southern branch, led by Abdyl Frashëri consisted of sixteen representatives from the areas of Kolonjë, Korçë, Arta, Berat, Parga, Gjirokastër, Përmet, Paramythia, Filiates, Margariti, Vlorë, Tepelenë and Delvinë.

The League of Prizren worked to gain autonomy for the Albanians and to thwart implementation of the Treaty of San Stefano, but not to create an independent Albania.

[58] In July 1878, the league sent a memorandum to the Great Powers at the Congress of Berlin, which was called to settle the unresolved problems of Turkish War, demanding that all Albanians be united in a single autonomous Ottoman province.

The Albanians' successful resistance to the treaty forced the Great Powers to alter the border, returning Gusinje and Plav to the Ottoman Empire and granting Montenegro the Albanian-populated coastal town of Ulcinj.

[76][77][78] Faced with growing international pressure "to pacify" the refractory Albanians, the sultan dispatched a large army under Dervish Turgut Pasha to suppress the League of Prizren and deliver Ulcinj to Montenegro.

[88] The Ottoman Empire continued to crumble after the Congress of Berlin and Sultan Abdül Hamid II resorted to repression to maintain order.

The imperial authorities disbanded a successor organisation Besa-Besë (League of Peja) founded in 1897, executed its president Haxhi Zeka in 1902, and banned Albanian-language books and correspondence.

[99][97][96][98][100] In 1906 opposition groups in the Ottoman Empire emerged, one of which evolved into the Committee of Union and Progress, more commonly known as the Young Turks, which proposed restoring constitutional government in Constantinople, by revolution if necessary.

[108][109] After securing the abdication of Abdül Hamid II in April 1909, the new authorities levied taxes, outlawed guerrilla groups and nationalist societies, and attempted to extend Constantinople's control over the northern Albanian mountain men.

[110][111] In addition, the Young Turks legalized the bastinado, or beating with a stick, even for misdemeanors, banned carrying rifles, and denied the existence of an Albanian nationality.

[113][114] Ottoman forces quashed these rebellions after three months, outlawed Albanian organizations, disarmed entire regions, and closed down schools and publications.

[115][116] Montenegro held ambitions of future expansion into neighbouring Albanian-populated lands and supported a 1911 uprising by the mountain tribes against the Young Turks regime that grew into a widespread revolt.

In a meeting of the committee held in Podgorica from 2 to 4 February 1911, under the leadership of Nikolla bey Ivanaj and Sokol Baci Ivezaj, it was decided to organise an Albanian uprising.

[127] As soon as he reached Shkodër on 11 May, he issued a general proclamation which declared martial law and offered an amnesty for all rebels (except for Malësor chieftains) if they immediately return to their homes.

[138][139][140] After a series of successes, Albanian revolutionaries managed to capture the city of Skopje, the administrative centre of Kosovo vilayet within the Ottoman rule.

Chaired by Britain's foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, the ambassadors' conference initially decided to create an autonomous Albania under continued Ottoman rule, but with the protection of the Great Powers.

This solution, as detailed in the Treaty of London, was abandoned in the summer of 1913 when it became obvious that the Ottoman Empire would, in the Second Balkan War, lose Macedonia and hence its overland connection with the Albanian-inhabited lands.

[160] The August 1913 Treaty of Bucharest established that independent Albania was a country with borders that gave the new state about 28,000 square kilometres of territory and a population of 800,000.

The treaty, however, left large areas with majority Albanian populations, notably Kosovo and western Macedonia, outside the new state and failed to solve the region's nationality problems.

[174] After a long time struggling with obstacles coming from the Ottoman authorities, the first secular school of Albanian language was opened on the initiative of individual teachers and other intellectuals on 7 March 1887 in Korce.

[179] However, the Congress was unable to make a clear decision and opted for a compromise solution of using both the widely used Istanbul, with minor changes, and a modified version of the Bashkimi alphabet.

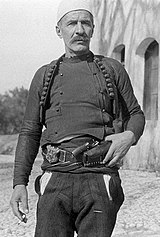

Isa Boletini .