Albanian alphabet

[10][11] Written either by archbishop Guillaume Adam or the monk Brocardus Monacus the report notes that Licet Albanenses aliam omnino linguam a latina habeant et diversam, tamen litteram latinam habent in usu et in omnibus suis libris ("Though the Albanians have a language entirely their own and different from Latin, they nevertheless use Latin letters in all their books").

[13] It was a simple phrase that was supposed to be used by the relatives of a dying person if they could not make it to churches during the troubled times of the Ottoman invasion.

The Greek intellectual Anastasios Michael, in his speech to the Berlin Academy (c. 1707) mentions an Albanian alphabet produced "recently" by Kosmas from Cyprus, bishop of Dyrrachium.

He then went to Malta, where he stayed until 1860 in a Protestant seminary, finishing the translation of The New Testament in the Tosk and Gheg dialects.

One of its members was Kostandin Kristoforidhi and the main purpose of the commission was the creation of a unique alphabet for all the Albanians.

As the albanologist Robert Elsie has written:[17] The predominance of Greek as the language of Christian education and culture in southern Albania and the often hostile attitude of the Orthodox church to the spread of writing in Albanian made it impossible for an Albanian literature in Greek script to evolve.

The Orthodox church, as the main vehicle of culture in the southern Balkans, while intent on spreading Christian education and values, was never convinced of the utility of writing in the vernacular as a means of converting the masses, as the Catholic church in northern Albania had been, to a certain extent, during the Counter-Reformation.

Nor, with the exception of the ephemeral printing press in Voskopoja, did the southern Albanians ever have at their disposal publishing facilities like those available to the clerics and scholars of Catholic Albania in Venice and Dalmatia.

As such, the Orthodox tradition in Albanian writing, a strong cultural heritage of scholarship and erudition, though one limited primarily to translations of religious texts and to the compilation of dictionaries, was to remain a flower which never really blossomed.The turning point was the aftermath of the League of Prizren (1878) events when in 1879 Sami Frashëri and Naim Frashëri formed the Society for the Publication of Albanian Writings.

Sami Frashëri, Koto Hoxhi, Pashko Vasa and Jani Vreto created an alphabet.

In 1905 this alphabet was in widespread use in all Albanian territory, North and South, including Catholic, Muslim and Orthodox areas.

However, the Congress was unable to make a clear decision and opted for a compromise solution of using both the widely used Istanbul, with minor changes, and a modified version of the Bashkimi alphabet.

Usage of the alphabet of Istanbul declined rapidly and it was essentially extinct over the following decades, due largely to its inconvenience in requiring new custom-made glyphs that Bashkimi did not.

During 1909 and 1910 there were movements by members of the Young Turks to adopt an Arabic alphabet, as they considered the Latin script to be un-Islamic.

The digraphs of the Albanian alphabet are the letters Dh, Gj, Ll, Nj, Rr, Sh, Th, Xh, and Zh.

Eja e t’ a dájmə baškə.“ „Me kênə mã e mađe, i þa e motəra, kišimə me e daə baškə; por mbassi âšt aḱ e vogelə, haje vetə.“ „Ani ča?

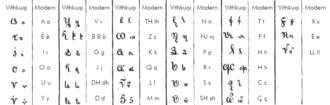

[22] In his Universal Geography published in 1826 Malte-Brun mentions an Albanian "ecclesiastical alphabet, which consists of thirty letters.

"[23] After him Johann Georg von Hahn, Leopold Geitler, Gjergj Pekmezi and others continued studies on the same topic.

The earliest Albanian sources were written by people educated in Italy, as a consequence, the value of the letters were similar to those of the Italian alphabet.

The present-day q was variously written as ⟨ch⟩, ⟨chi⟩, ⟨k⟩, ⟨ky⟩, ⟨kj⟩, k with dot (Leake 1814) k with overline (Reinhold 1855), k with apostrophe (Miklosich 1870), and ⟨ḱ⟩ (first used by Lepsius 1863).

However, also used were Greek rho (ρ) (Miklosich 1870), ⟨ṙ⟩ (Kristoforidis 1872), ⟨rh⟩ (Dozon 1878 and Grammaire albanaise 1887), ⟨r̄⟩ (Meyer 1888 and 1891), ⟨r̀⟩ (Alimi) and ⟨p⟩ (Frasheri, who used a modified ⟨p⟩ for [p]).

Formerly, it was written variously as a backward 3, Greek zeta (ζ) (Reinhold 1855), ⟨x⟩ (Bashkimi) and a symbol similar to ⟨p⟩ (Altsmar).

This sound was variously written as an overlined ζ (Reinhold 1855), ⟨sg⟩ (Rada 1866), ⟨ž⟩, ⟨j⟩ (Dozon 1878), underdotted z, ⟨xh⟩ (Bashkimi), ⟨zc⟩.