Rhyme dictionary

The later rime tables gave a significantly more precise and systematic account of the sounds of these dictionaries by tabulating syllables by their onsets, rhyme groups, tones and other properties.

Some scholars use the French spelling rime, as used by the Swedish linguist Bernard Karlgren, for the categories described in these works, to distinguish them from the concept of poetic rhyme.

[1] Chinese scholars produced dictionaries to codify reading pronunciations for the correct recitation of the classics and the associated rhyme conventions of regulated verse.

'sound types') by Li Deng (李登) of the Three Kingdoms period, containing more than 11,000 characters grouped under the five notes of the ancient Chinese musical scale.

[7] According to Lu Fayan's preface, the initial plan of the work was drawn up 20 years earlier in consultation with a group of scholars, three from southern China and five from the north.

[10][12] Lu's initial work was primarily a guide to pronunciation, with very brief glosses, but later editions included expanded definitions, making them useful as dictionaries.

[11] Until the mid-20th century, the oldest complete rime dictionaries known were the Guangyun and Jiyun, though extant copies of the latter were marred by numerous transcription errors.

[12][13] When the Qieyun became the national standard in the Tang dynasty, several copyists were engaged in producing manuscripts to meet the great demand for revisions of the work.

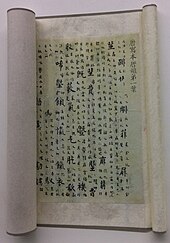

Particularly prized were copies of Wáng Rénxū's edition, made in the early 9th century, by Wú Cǎiluán (呉彩鸞), a woman famed for her calligraphy.

Today, these final stops are generally preserved in southern varieties of Chinese, but have disappeared in most northern ones, including the standard language.

A few entries are re-ordered to place corresponding rhyme groups of different tones in the same row, and darker lines separate the tóngyòng groups: The rime dictionaries have been intensively studied as important sources on the phonology of medieval Chinese, and the system they reveal has been dubbed Middle Chinese.

The initials are further analysed in terms of place and manner of articulation, suggesting inspiration from Indian linguistics, at that time the most advanced in the world.

[37] In his Qièyùn kǎo (1842), the Cantonese scholar Chen Li set out to identify the initial and final categories underlying the fanqie spellings in the Guangyun.

[39][40][41] Unaware of Chen's work, the Swedish linguist Bernard Karlgren repeated the analysis identifying the initials and finals in the 1910s.

The so-called Sino-Xenic pronunciations, readings of Chinese loanwords in Vietnamese, Korean and Japanese, were ancient, but affected by the different phonological structures of those languages.

Finally modern varieties of Chinese provided a wealth of evidence, but often influenced each other as a result of a millennium of migration and political upheavals.

After applying a variant of the comparative method in a subsidiary role to flesh out the rime dictionary evidence, Karlgren believed that he had reconstructed the speech of the Sui-Tang capital Chang'an.

[49] Assigning phonetic values to the finals has proved more difficult, as many of the distinctions reflected in the Qieyun have been lost over time.

Some authors argue that the placement of the first four rhyme groups in the Qieyun suggests that they had distinct codas, reconstructed as labiovelars /ŋʷ/ and /kʷ/.

[64] Although Karlgren's identification of the Qieyun system with a Sui-Tang standard is no longer accepted, the fact that it contains more distinctions than any single contemporary form of speech means that it retains more information about earlier stages of the language, and is a major component in the reconstruction of Old Chinese phonology.

However, the fine distinctions made by the Qieyun were found overly restrictive by poets, and Xu Jingzong and others suggested more relaxed rhyming rules.

[72] Though no longer extant, it served as the model for a series of encyclopedic dictionaries of literary words and phrases organized by Píngshuǐ rhyme groups, culminating in the Peiwen Yunfu (1711).

[75] The early Ming dictionary Yùnluè yìtōng (韻略易通) by Lan Mao was based on the Zhongyuan Yinyun, but arranged the homophone groups according to a fixed order of initials, which were listed in a mnemonic poem in the ci form.

Further innovations are found in a rime dictionary from the late 16th century describing the Fuzhou dialect, which is preserved, together with a later redaction, in the Qi Lin Bayin.

Mikhail Sofronov applied Chen Li's method to these fanqie to construct the system of Tangut initials and finals.