Rings of Uranus

In the order of increasing distance from the planet the 13 known rings are designated 1986U2R/ζ, 6, 5, 4, α, β, η, γ, δ, λ, ε, ν and μ.

The relative lack of dust in the ring system may be due to aerodynamic drag from the extended Uranian exosphere.

After colliding, the moons probably broke up into many particles, which survived as narrow and optically dense rings only in strictly confined zones of maximum stability.

[4] The definitive discovery of the Uranian rings was made by astronomers James L. Elliot, Edward W. Dunham, and Jessica Mink on March 10, 1977, using the Kuiper Airborne Observatory, and was serendipitous.

[5][6] The five occultation events they observed were denoted by the Greek letters α, β, γ, δ and ε in their papers.

[9] In 1982, on the fifth anniversary of the rings' discovery, Uranus along with the eight other planets recognized at the time (i.e. including Pluto) aligned on the same side of the Sun.

[12] The Hubble Space Telescope detected an additional pair of previously unseen rings in 2003–2005, bringing the total number known to 13.

[13] Hubble also imaged two small satellites for the first time, one of which, Mab, shares its orbit with the outermost newly discovered μ ring.

In order of increasing distance from the planet they are: 1986U2R/ζ, 6, 5, 4, α, β, η, γ, δ, λ, ε, ν, μ rings.

[18] These faint rings and dust bands may exist only temporarily or consist of a number of separate arcs, which are sometimes detected during occultations.

The nature of this material is not clear, but it may be organic compounds considerably darkened by the charged particle irradiation from the Uranian magnetosphere.

[24] As the ring becomes wider, the amount of shadowing between particles decreases and more of them come into view, leading to higher integrated brightness.

Indeed, occultation observations conducted from the ground and the spacecraft showed that its normal optical depth[c] varies between 0.5 and 2.5,[24][25] being highest near the periapsis.

[24] The ring is almost devoid of dust, possibly due to the aerodynamic drag from Uranus' extended atmospheric corona.

[12][30] When observed in forward-scattering geometry by Voyager 2, the δ ring appeared relatively bright, which is compatible with the presence of dust in its broad component.

[19] The same event revealed a thick and optically thin dust band just outside the β ring, which was also observed earlier by Voyager 2.

When viewed in back-scattered light,[e] the λ ring is extremely narrow—about 1–2 km—and has the equivalent optical depth 0.1–0.2 km at the wavelength 2.2 μm.

The equivalent depth is as high as 0.36 km in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum, which explains why λ ring was initially detected only in UV stellar occultations by Voyager 2.

[15] This observation, together with the wavelength dependence of the optical depth, indicates that the λ ring contains significant amount of micrometre-sized dust.

[12] Many of these bands were detected again in 2003–2004 by the Keck Telescope and during the 2007 ring-plane crossing event in backscattered light, but their precise locations and relative brightnesses were different from during the Voyager observations.

[22] This failure means that the μ ring is blue in color, which in turn indicates that very small (submicrometer) dust predominates within it.

[9] The most widely cited model for such confinement, proposed initially by Goldreich and Tremaine,[39] is that a pair of nearby moons, outer and inner shepherds, interact gravitationally with a ring and act like sinks and donors, respectively, for excessive and insufficient angular momentum (or equivalently, energy).

[27] Every such disruption would have started a collisional cascade that quickly ground almost all large bodies into much smaller particles, including dust.

[9] Eventually the majority of mass was lost, and particles survived only in positions that were stabilized by mutual resonances and shepherding.

The dust has a very short lifetime, 100–1000 years, and should be continuously replenished by collisions between larger ring particles, moonlets and meteoroids from outside the Uranian system.

[15][27] The belts of the parent moonlets and particles are themselves invisible due to their low optical depth, while the dust reveals itself in forward-scattered light.

[27] The narrow main rings and the moonlet belts that create dust bands are expected to differ in particle size distribution.

Such a distribution increases the surface area of the material in the rings, leading to high optical density in back-scattered light.

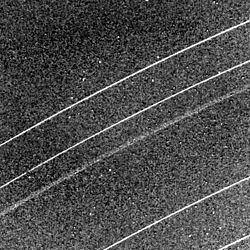

[18] Voyager 2 observed the rings in different geometries relative to the Sun, producing images with back-scattered, forward-scattered and side-scattered light.

[12] Analysis of these images allowed derivation of the complete phase function, geometrical and Bond albedo of ring particles.