Miranda (moon)

It was discovered by Gerard Kuiper on 16 February 1948 at McDonald Observatory in Texas, and named after Miranda from William Shakespeare's play The Tempest.

At just 470 km (290 mi) in diameter, Miranda is one of the smallest closely observed objects in the Solar System that might be in hydrostatic equilibrium (spherical under its own gravity), and its total surface area is roughly equal to that of the U.S. state of Texas.

Miranda was discovered on 16 February 1948 by planetary astronomer Gerard Kuiper using the McDonald Observatory's 82-inch (2,080 mm) Otto Struve Telescope.

[20] The discovery team had expected Miranda to resemble Mimas, and found themselves at a loss to explain the moon's unique geography in the 24-hour window before releasing the images to the press.

[21] In 2017, as part of its Planetary Science Decadal Survey, NASA evaluated the possibility of an orbiter to return to Uranus some time in the 2020s.

[24] Miranda's surface may be mostly water ice, though it is far rockier than its corresponding satellites in the Saturn system, indicating that heat from radioactive decay may have led to internal differentiation, allowing silicate rock and organic compounds to settle in its interior.

Only water has been detected so far on Miranda's surface, though it has been speculated that methane, ammonia, carbon monoxide or nitrogen may also exist at 3% concentrations.

[20] A study published in 2024 suggests that Miranda might have had a liquid ocean of about 100 km thickness beneath the surface within the last 100-500 million years.

[28][29] Precisely how a body as small as Miranda could have enough internal energy to produce the myriad geological features seen on its surface has not been established with certainty,[26] though the currently favoured hypothesis is that it was driven by tidal heating during a past time when it was in 3:1 orbital resonance with Umbriel.

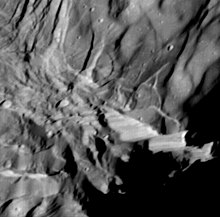

They feature complex sets of parallel ridges and rupes (fault scarps) as well as numerous outcrops of bright and dark materials, suggesting an exotic composition.

[37] They designate major regions of Miranda where hilly terrain and plains follow one another, more or less dominated by ancient impact craters.

This region is characterized by a central geological structure which takes the shape of a luminous chevron,[41] a surface with a relatively high albedo, and a series of gorges which extend northwards from a point near the pole.

[42] The outer boundary of Inverness, as well as its internal patterns of ridges and bands of contrasting albedos, form numerous salient angles.

[44] Arden Corona, present in the front hemisphere of Miranda, extends over approximately 300 km (190 mi) from east to west.

The outer margin of this corona forms parallel and dark bands which surround in gentle curves a more clearly rectangular core at least 100 km (62 mi) wide.

It is also characterized by a mottled pattern resulting from large patches of relatively bright material scattered over a generally dark surface.

[45] This succession of escarpments gradually pushes the land into a deep hollow along the border between Arden and the crateriform terrain called Mantua Regio.

[40] The topography of the core of Elsinore consists of a complex set of intersections of troughs and bumps which are truncated by this outer belt which is marked by roughly concentric linear ridges.

This network of faults begins on the northwest side of Inverness where it forms a deep gorge on the outer edge of the ovoid which surrounds the crown.

[40] Although it could not be observed by the Voyager 2 probe on the face immersed in the polar night of Miranda, it is probable that this geological structure extends beyond the terminator in the northern hemisphere.

Scientists use these as "planetary chronometers"; they count observed craters to date the formation of the terrain of inert natural satellites devoid of atmospheres, such as Callisto.

[47] In Matuna Regio, between the craters Truncilo and Fransesco, there is a gigantic circular geological structure of 170 km (110 mi) in diameter which could be a basin impact very significantly degraded.

[51] The data from the impact craters can be interpreted as follows: the interior and marginal zones of the corona, including most of the albedo bands, were formed during the same period of time.

[51] Their formation was followed by later tectonic developments which produced the high-relief fault scarps observed along the edge of the crown near longitude 110°.

[58] However, thermal models applicable to moons the size of Miranda predict rapid cooling and the absence of geological evolution following its accretion from the subnebula.

[58] The bottoms of the oldest craters are thus partially covered with material from the depths of the moon referred to as endogenous resurfacing, which was a surprising observation.

[58] The most satisfactory explanation for the origin of the heat which animated the moon is the one which also explains the volcanism on Io: a situation of orbital resonance now on Miranda and the important phenomenon of tidal forces generated by Uranus.

[57] After this first geological epoch, Miranda experienced a period of cooling which generated an overall extension of its core and produced fragments and cracks of its mantle on the surface, in the form of grabens.

[55] It is possible that at this time, the moon was distorted to the point that its asphericity and eccentricity temporarily caused it to undergo a chaotic rotational movement, such as that observed on Hyperion.

[65] After Miranda escaped from this resonance with Umbriel, through a mechanism that likely moved the moon into its current, abnormally high orbital tilt, the eccentricity would have been reduced.