Titania (moon)

At a diameter of 1,578 kilometres (981 mi) it is the eighth largest moon in the Solar System, with a surface area comparable to that of Australia.

Titania consists of approximately equal amounts of ice and rock, and is probably differentiated into a rocky core and an icy mantle.

Measurements during Titania's occultation of a star put an upper limit on the surface pressure of any possible atmosphere at 1–2 mPa (10–20 nbar).

[13] For nearly the next 50 years, Titania and Oberon would not be observed by any instrument other than William Herschel's,[14] although the moon can be seen from Earth with a present-day high-end amateur telescope.

[15] The names of all four satellites of Uranus then known were suggested by Herschel's son John in 1852, at the request of William Lassell,[16] who had discovered the other two moons, Ariel and Umbriel, the year before.

[20] In 1851 Lassell eventually numbered all four known satellites in order of their distance from the planet by Roman numerals, and since then Titania has been designated Uranus III.

Titania orbits Uranus at the distance of about 436,000 kilometres (271,000 mi), being the second farthest from the planet among its five major moons after Oberon.

[23] The cause of this asymmetry is not known, but it may be related to the bombardment by charged particles from the magnetosphere of Uranus, which is stronger on the trailing hemisphere (due to the plasma's co-rotation).

[23] Except for water, the only other compound identified on the surface of Titania by infrared spectroscopy is carbon dioxide, which is concentrated mainly on the trailing hemisphere.

It might be produced locally from carbonates or organic materials under the influence of the solar ultraviolet radiation or energetic charged particles coming from the magnetosphere of Uranus.

Recent studies suggest, contrary to earlier theories, that Uranus largest moons like Titania in fact could have active subsurface oceans.

[32] However, fresh impact deposits are bluer, while the smooth plains situated on the leading hemisphere near Ursula crater and along some grabens are somewhat redder.

[32] The reddening of the surfaces probably results from space weathering caused by bombardment by charged particles and micrometeorites over the age of the Solar System.

[32] However, the color asymmetry of Titania is more likely related to accretion of a reddish material coming from outer parts of the Uranian system, possibly, from irregular satellites, which would be deposited predominately on the leading hemisphere.

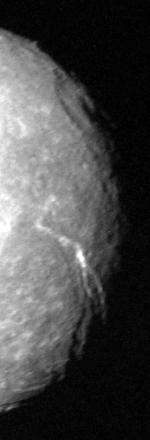

[34] Scientists have recognized three classes of geological feature on Titania: craters, chasmata (canyons) and rupes (scarps).

[33] Some craters (for instance, Ursula and Jessica) are surrounded by bright impact ejecta (rays) consisting of relatively fresh ice.

[37] The most prominent among Titania's canyons is Messina Chasma, which runs for about 1,500 kilometres (930 mi) from the equator almost to the south pole.

The resurfacing may have been either endogenic in nature, involving the eruption of fluid material from the interior (cryovolcanism), or, alternatively it may be due to blanking by the impact ejecta from nearby large craters.

[37] The most recent endogenous processes were mainly tectonic in nature and caused the formation of the canyons, which are actually giant cracks in the ice crust.

[37] The presence of carbon dioxide on the surface suggests that Titania may have a tenuous seasonal atmosphere of CO2, much like that of the Jovian moon Callisto.

At the maximum temperature attainable during Titania's summer solstice (89 K), the vapor pressure of carbon dioxide is about 300 μPa (3 nbar).

[5] This upper limit is still several times higher than the maximum possible surface pressure of the carbon dioxide, meaning that the measurements place essentially no constraints on parameters of the atmosphere.

[5] The peculiar geometry of the Uranian system causes the moons' poles to receive more solar energy than their equatorial regions.

Titania is thought to have lost a significant amount of carbon dioxide since its formation 4.6 billion years ago.

[39] The moons that formed in such a subnebula would contain less water ice (with CO and N2 trapped as a clathrate) and more rock, explaining their higher density.

[40] After the end of formation, the subsurface layer cooled, while the interior of Titania heated due to decay of radioactive elements present in its rocks.

[45] A Uranus orbiter[46] had previously been listed as the third priority for a NASA Flagship mission by the 2013–2022 Planetary Science Decadal Survey.