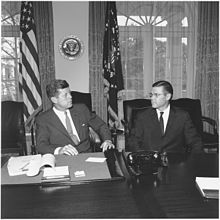

Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (/ˈmæknəmærə/; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American businessman and government official who served as the eighth United States secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson at the height of the Cold War.

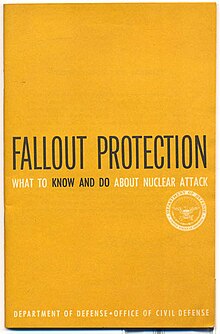

These moves were significant because McNamara was abandoning President Dwight D. Eisenhower's policy of massive retaliation in favor of a flexible response strategy that relied on increased U.S. capacity to conduct limited, non-nuclear warfare.

The Kennedy administration placed particular emphasis on improving the ability to counter communist "wars of national liberation", in which the enemy avoided head-on military confrontation and resorted to political subversion and guerrilla tactics.

He also approved Operation Chrome Dome in 1961, in which some B-52 strategic bomber aircraft armed with thermonuclear weapons remained on continuous airborne alert, flying routes that put them in positions to attack targets in the Soviet Union if they were ordered to do so.

The secretary believed that the United States could afford any amount needed for national security, but that "this ability does not excuse us from applying strict standards of effectiveness and efficiency to the way we spend our defense dollars.... You have to make a judgment on how much is enough.

[43][44] Conversely, his actions in mandating a premature across-the-board adoption of the untested M16 rifle proved catastrophic when the weapons began to fail in combat, though later congressional investigations revealed the causes of these failures as negligence and borderline sabotage on behalf of the Army ordnance corps' officers.

[62] At a meeting on 29 April 1961, when questioned by the Attorney General, Robert F. Kennedy, McNamara stated that "we should take a stand in Thailand and South Vietnam", pointedly omitting Laos from the nations in Southeast Asia to risk a war over.

[71] In 1962, McNamara supported a plan for mass spraying of the rice fields with herbicides in the Phu Yen mountains to starve the VC out, but this was stopped when Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs W. Averell Harriman pointed out to Kennedy that the ensuing famine would kill thousands of innocent people.

[81] On 31 August 1963, Paul Kattenburg, a newly returned diplomat from Saigon suggested at a meeting attend by Rusk, McNamara and Vice President Johnson that the United States should end support for Diệm and leave South Vietnam to its fate.

[96] After returning to Washington on 13 March, McNamara reported to Johnson that the situation had "unquestionably been growing worse": since his last visit in December 1963 with 40% of the countryside now under "Vietcong control or predominant influence", most of the South Vietnamese people were displaying "apathy and indifference", the desertion rate in the ARVN was "high and increasing" while the VC were "recruiting energetically".

[99] To compensate for the weaknesses of the South Vietnamese state, by late winter of 1964, senior officials in the Johnson administration such as McNamara's deputy, William Bundy, the assistant secretary of defense, were advocating American intervention in the war.

[112] Though Johnson now had the authority to wage war, he proved reluctant to use it, for example by rejecting the advice of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to bomb North Vietnam after a VC attack on Bien Hoa Air Base killed five Americans and destroyed 5 B-57 bombers.

[122] After the bombing raids started, MACV commander General William Westmoreland, cabled Johnson to say that Da Nang Air Base was vulnerable as he had no faith in the ability of the South Vietnamese to protect it, leading him to ask for American troops to be deployed instead.

[138] In a 1966 memo, McNamara admitted that the sort of counterinsurgency war envisioned by Kennedy with the Special Forces leading the fight had not occurred and wrote that the responsibility for this "undoubtedly lies with bad management" on the part of the Army.

[118] Karnow, one of the journalists present during the "off-the-record" conversation, described McNamara's personality as having changed, noting the Defense Secretary, who was normally so arrogant and self-assured, convinced he could "scientifically" solve any problem, as being subdued and clearly less self-confident.

[118] After long study, in September 1966 McNamara ordered the construction of a barrier line to detect the infiltration of North Vietnamese forces into southern Laos, South Vietnam, and Cambodia that would help direct air strikes.

[145] In October 1966, he launched Project 100,000, the lowering of military Armed Forces Qualification Test standards, which allowed 354,000 additional men to be recruited, despite criticism that they were not suited to working in high-stress or dangerous environments.

[148] McNamara agreed to the debate, and standing on the hood of his car answered the charge from a student in the crowd that the United States was waging aggression by saying the war started in 1954, not 1957, which he knew "because the International Control Commission wrote a report that said so.

[155] The economic sacrifices that ending the peacetime economy would entail would make it almost politically impossible to negotiate peace, and in effect would mean placing the hawks in charge, which was why those of a hawkish inclination kept pressing for the Reserves to be called up.

[156] The task was assigned to Gelb and six officials whom McNamara instructed to examine just how and why the United States became involved in Vietnam, by answering his list of 100 questions starting with American relations with the Viet Minh in World War II.

[158] Though Gelb was a hawk who had written pro-war speeches for the Republican Senator Jacob Javits, he and his team, which grew to 36 members by 1969, became disillusioned as they wrote the history; at one point when discussing what were the lessons of Vietnam, future general Paul F. Gorman, one of the historians, went up to the blackboard to write simply, "Don't.

The directive declared, "Every military commander has the responsibility to oppose discriminatory practices affecting his men and their dependents and to foster equal opportunity for them, not only in areas under his immediate control, but also in nearby communities where they may live or gather in off-duty hours."

[174] In July 1966, McNamara told Johnson that it was "absolutely essential" for the British to remain "East of Suez", citing political rather military reasons, namely that it showed the importance of the region, which thus justified the America's involvement in Vietnam.

This led Stennis to schedule hearings for the Senate Armed Forces Committee in August 1967 to examine the charge that "unskilled civilian amateurs" (i.e. McNamara) were not letting "professional military experts" win the war.

[183] The hearings opened on 8 August 1967, and Stennis called as his witnesses numerous admirals and Air Force generals who all testified to their belief that the United States was fighting with "one arm tied behind its back", implicitly criticizing McNamara's leadership.

[184] McNamara concluded that only some sort of genocide could actually win the war, stating: "Enemy operations in the south cannot, on the basis of any reports I have seen be stopped by air bombardment-short, that is, of the virtual annihilation of North Vietnam and its people".

[189] The historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr stated that he was present during a conversation between McNamara and Senator Kennedy during which the former told the latter that he only learned from reading the newspapers of Johnson's announcement that he had just "resigned" as Defense Secretary and had been appointed president of the World Bank.

[211] Craig McNamara, who was visiting the United States at the time of the coup and chose not to return to Chile was outraged by the decision to resume the loans, telling his father in a phone call: "You can't do this-you always say the World Bank is not a political institution, but financing Pinochet clearly would be".

[220] Despite his role as one of the architects of Operation Rolling Thunder, McNamara met with a surprisingly warm reception, even from those who survived the bombing raids, and was often asked to autograph pirate editions of In Retrospect which had been illegally translated and published in Vietnam.

She was married to Ernest Byfield, a former OSS officer and Chicago hotel owner, thirty years her senior, whose first wife, Gladys Rosenthal Tartiere, leased her 400-acre (1.6 km2) Glen Ora estate in Middleburg, Virginia, to John F. Kennedy during his presidency.