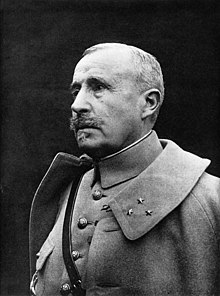

Robert Nivelle

Robert Georges Nivelle[a] (15 October 1856[1] – 22 March 1924[2]) was a French artillery general officer who served in the Boxer Rebellion and the First World War.

In May 1916, he succeeded Philippe Pétain as commander of the French Second Army in the Battle of Verdun, leading counter-offensives that rolled back the German forces in late 1916.

to have squandered the lives of his soldiers in wasteful counter-attacks during the Battle of Verdun; only one fresh reserve brigade was left with the Second Army by 12 June.

[11] After the Germans captured Fleury on 23 June, Nivelle issued an Order of the Day which ended with the now-famous line: Ils ne passeront pas!

These tactics proved effective: French troops re-took Fleury on 24 October, as well as Fort Douaumont, whose capture by the Germans on 25 February 1916 had been highly celebrated in Germany.

He was placed under the orders of the War Minister Hubert Lyautey and, unlike Joffre, Nivelle's authority did not extend over the Salonika front.

[15] He believed that a saturation bombardment, followed by a creeping barrage and by aggressive infantry assaults, could break the enemy's front defences and help French troops reach the German gun-line during a single attack, which would be followed by a breakthrough within two days.

By Edward Spears' account Nivelle accused Haig of having "une idée fixe" about Flanders and of trying to "hog all the blanket for himself" rather than seeing the front as a whole.

David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, backed Nivelle because he thought he had "proved himself to be a Man" at Verdun.

At the Calais Conference the railway experts were soon sent away, and although Nivelle became embarrassed when Lloyd George asked him to criticise Haig, he agreed to draw up rules for the relations between the British and French armies, to be binding also on their successors going forward.

The British CIGS Robertson lost his temper when shown the proposals, and believed that Lloyd George, not the French, had originated them.

As a compromise Haig was given right of appeal to the War Cabinet and retained tactical control of British forces, although Lloyd George insisted – lest the conference break up without agreement - that he still be under Nivelle's orders for the duration of the offensive.

Nivelle also believed that Lloyd George hoped to become Allied Commander-in-Chief, a suggestion so absurd that it caused President Poincaré to laugh.

At another conference in London (12-13 March) Lloyd George stressed that the BEF must not be "mixed up with the French Army", and Haig and Nivelle met with Robertson and Lyautey to settle their differences.

[29] The French General Franchet d'Esperey, commander of the Northern Army Group, asked Nivelle if he could attack the Germans as they withdrew.

[31] General Micheler, commander of the French Reserve Army Group, which was to exploit the expected breakthrough on the Aisne, had serious misgivings about the upcoming battle.

On 6 April, Nivelle met with Micheler, Pétain and several politicians, including President Poincaré and Minister of War Painlevé at Compiegne.

[32] Painlevé argued that the Russian Revolution meant that France shouldn't expect any major help from Russia, and that the offensive should be delayed until American forces were available and could get involved.

Micheler and Petain said that they doubted the French force allocated to the attack could penetrate beyond the second line of the German defences, and suggested a more limited operation.

Micheler convinced Nivelle to reduce the scope of the offensive, with the goal now only to secure all of the Chemin des Dames and push the Germans back from Reims.

On 29 April, Nivelle's authority was undermined by the appointment of Pétain as Chief of the General Staff, and thus the main military adviser to the government.

[39] Although this was far fewer than the casualties in the Battle of Verdun, Nivelle had predicted a great success, and the country expressed bitter disappointment.

"By the 20th of April they had in their hands over 20,000 prisoners and 147 guns; the railway from Soissons to Reims was freed, the enemy had been driven out of the Aisne valley west of the Oise—Aisne Canal; the German second position had been captured south of Juvincourt; and in Champagne some of the most important 'monts' had been taken.

In The Macmillan Dictionary of the First World War, he is described as "a competent tactician as a regimental colonel in 1914",[45] that his creeping barrage tactics were "innovative",[46] and that he was able to galvanize "increasingly pessimistic public opinion in France" in December 1916".