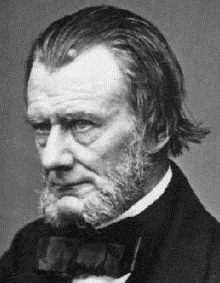

Robert Willis (engineer)

He was promoted to a Foundation Fellow in 1829, and became Steward of the College, positions he held until his marriage, in 1832, to Mary Anne, daughter of Charles Humfrey of Cambridge.

His theory that the vowel sound depended on a single harmonic frequency in addition to the principal pitch is today regarded as too simple, but his work was the first systematic investigation in the field, and provided a valuable basis for later studies.

[12] From 1837 to 1875 Willis served as Jacksonian Professor of Natural Philosophy at Cambridge, and from 1853 onward he was a lecturer in applied mechanics at the government school of mines.

Principles of Mechanism, Willis's major engineering work, provided a mathematical analysis of the "relations of motions".

It contrasted with earlier approaches in that it was not concerned with utility – a crank is defined as a machine for converting reciprocating to circular motion, or vice versa, whether it is used for raising water, grinding flour or sawing timber.

He classified machines in two ways, firstly in terms of the type of contact: rolling, sliding, wrapping, linking and reduplicating; and second on whether the relationship between the connected motions was fixed or variable.

His approach to architectural style recognised a difference between the real and the apparent structure of a building, which he referred to as the mechanical and the decorative aspects, respectively.

An arch appears to be supported by the capital from which is springs, but the actual forces may be exerted at a different point, as illustrated in the figure to the right.

In reality the structure is the entire column, supplemented by the lateral buttressing that is needed to take the transverse thrust of the vault.

For the result to be aesthetically pleasing, it is the apparent (decorative) structure that must satisfy the eye as to the stability and harmony of the building [20][2]: 84–86 Willis also considered the origin of the pointed arch.

As he put it in his Architectural history of Canterbury Cathedral: "My plan therefore has been, first to collect all the written evidence, and then by a close comparison of it with the building itself, to make the best identification of one with the other that I have been able.

[25][2]: 171–185 His 1845 publication on Canterbury was, as noted by Buchanan, the first work in the English language to be entitled an "architectural history"".

Willis quotes extensively from the sources, including his own complete translation of Gervase's account, which covers the fire of 1174 and the subsequent rebuilding.

Willis pointed out visible consequences, in particular columns that had been inserted into the crypt to provide support for those in the upper structure, that no longer corresponded to the old layout.

Buchanan (2019) gives an account of the 1861 Peterborough meeting, contrasting the roles of local antiquarians and national experts such as Willis.

[31] He shows his usual skill in explicating the various stages of the buildings he examines, but also pays more attention to aspects of everyday life.

For example in discussing the building known as the necessarium, i.e. latrine, he cites the instructions give by Archbishop Lanfrance to the watchman to examine all the sedilia at night in case any of the monks have fallen asleep.

This was an early example of historically accurate gothic in England, and in this respect Willis was in agreement with the prescriptions of the Society.

[34]: 16–17 The Society, however, did not approve of the restoration of Ely Cathedral, for which Willis provided advice and drawings, including a design for a stone arcade for the communion table.

George Peacock, Dean of Ely, was a reformer, and wished to open up the eastern part of the cathedral for the congregation.

[2]: 301–306 Willis was an early member of the British Archaeological Association, and gave his paper on Canterbury Cathedral at their first meeting in 1844.

[4][38] He was one of the jurors in the Great Exhibition of 1851, and his lecture On machines and tools for working in metal, wood and other materials was published in the following year.

Pevsner (1970) lists some the books which included 26 editions of Vitruvius, works on Palmyra and on Chinese buildings, as well as those on German, French, Italian and British architecture[34]: 24–26 .

[40] He willed his manuscript on the Architectural History of the University of Cambridge to his nephew John Willis Clark who completed it (published 1886).

As with his cathedral studies, he made extensive use of documentary material, including University and College statutes and account books.

[2]: 346–349 In architectural terms, he emphasised the relationship between Oxford and Cambridge colleges on the one hand and monastic foundations, and also similarities in the layouts of private houses.

Sometimes, it is the other way round, and Thierry Mandoul's Entre raison et utopie: l'Histoire de l'architecture d'Auguste Choisy (2008) gives the dates (1799–1878) for our Willis who worked in architecture.