Rock magnetism

An understanding of remanence helps paleomagnetists to develop methods for measuring the ancient magnetic field and correct for effects like sediment compaction and metamorphism.

With such methods, rock magnetists can measure the effects of past climate change and human impacts on the mineralogy (see environmental magnetism).

In sediments, a lot of the magnetic remanence is carried by minerals that were created by magnetotactic bacteria, so rock magnetists have made significant contributions to biomagnetism.

Until the 20th century, the study of the Earth's field (geomagnetism and paleomagnetism) and of magnetic materials (especially ferromagnetism) developed separately.

[1] Koenigsberger (1938), Thellier (1938) and Nagata (1943) investigated the origin of remanence in igneous rocks.

In 1949, Louis Néel developed a theory that explained these observations, showed that the Thellier laws were satisfied by certain kinds of single-domain magnets, and introduced the concept of blocking of TRM.

[2] When paleomagnetic work in the 1950s lent support to the theory of continental drift,[3][4] skeptics were quick to question whether rocks could carry a stable remanence for geological ages.

To get at the stable part, they took to "cleaning" samples by heating them or exposing them to an alternating field.

However, later events, particularly the recognition that many North American rocks had been pervasively remagnetized in the Paleozoic,[6] showed that a single cleaning step was inadequate, and paleomagnetists began to routinely use stepwise demagnetization to strip away the remanence in small bits.

Paramagnetism is a weak positive response to a magnetic field due to rotation of electron spins.

Paramagnetism occurs in certain kinds of iron-bearing minerals because the iron contains an unpaired electron in one of their shells (see Hund's rules).

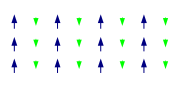

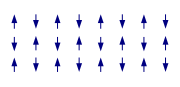

In the strict sense, ferromagnetism refers to magnetic ordering where neighboring electron spins are aligned by the exchange interaction.

Louis Néel identified four types of temperature dependence, one of which involves a reversal of the magnetization.

When an igneous rock cools, it acquires a thermoremanent magnetization (TRM) from the Earth's field.

TRM is the main reason that paleomagnetists are able to deduce the direction and magnitude of the ancient Earth's field.

When a mineral such as magnetite cools below the Curie temperature, it becomes ferromagnetic but is not immediately capable of carrying a remanence.

In studying the magnetism of rocks the specimen has to be broken off with a geological hammer and then carried to the laboratory.

It is supposed that in the process its magnetism does not change to any important extent, and though I have often asked how this comes to be the case I have never received any answer.Jeffreys 1959, p. 371