Thermae

Thermae usually refers to the large imperial bath complexes, while balneae were smaller-scale facilities, public or private, that existed in great numbers throughout Rome.

Thermae, balneae, balineae, balneum and balineum may all be translated as 'bath' or 'baths', though Latin sources distinguish among these terms.

The diminutive balneolum is adopted by Seneca[8] to designate the bathroom of Scipio in the villa at Liternum, and is expressly used to characterize the modesty of republican manners as compared with the luxury of his own times.

Pliny also, in the same sentence, makes use of the neuter plural balnea for public, and of balneum for a private bath.

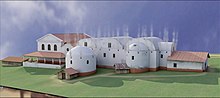

Passing through the principal entrance, a (barely visible, right side, one third of the total length from above), which is removed from the street by a narrow footway surrounding the building and after descending three steps, the bather would find a small chamber on his left (x) with a toilet (latrina), and proceed into a covered portico (g, g), which ran round three sides of an open court (palaestra,[clarification needed] A).

The room (f) which runs back from the portico, might have been appropriated to him; but most probably it was an oecus or exedra, for the convenience of the better classes while awaiting the return of their acquaintances from the interior.

It did not contain water either at Pompeii nor at the Baths of Hippias, but was merely heated with warm air of an agreeable temperature, in order to prepare the body for the great heat of the vapour and warm baths, and, upon returning, to prevent a too-sudden transition to the open air.

The compartments are divided from each other by figures of the kind called atlantes or telamones, which project from the walls and support a rich cornice above them in a wide arch.

In the Forum Baths at Pompeii the floor is mosaic, the arched ceiling adorned with stucco and painting on a coloured ground, the walls red.

At one end was a round basin (labrum), and at the other a quadrangular bathing place (puelos, alveus, solium, calida piscina), approached from the platform by steps.

It was already considerably heated from its contiguity to the furnace and the hypocaust below it, so that it supplied the deficiency of the former without materially diminishing its temperature; and the vacuum in this last was again filled up from the farthest removed, which contained the cold water received directly from the square reservoir seen behind them.

The boilers themselves no longer remain, but the impressions which they have left in the mortar in which they were embedded are clearly visible, and enable us to determine their respective positions and dimensions.

The entrance is by the door b, which conducts into a small vestibule (m) and from there into the apodyterium (H), which, like the one in the men's bath, has a seat (pulvinus, gradus) on either side built up against the wall.

Opposite to the door of entrance into the apodyterium is another doorway which leads to the tepidarium (G), which also communicates with the thermal chamber (F), on one side of which is a warm bath in a square recess, and at the farther extremity the labrum.

The baths often included, aside from the three main rooms listed above, a palaestra, or outdoor gymnasium where men would engage in various ball games and exercises.

The modern equivalent would be a combination of a library, art gallery, mall, restaurant, gym, and spa.

Many in the general public did not have access to the grand libraries in Rome and so as a cultural institution the baths served as an important resource where the more common citizen could enjoy the luxury of books.

The presence of niches in the walls are assumed to have been bookcases and have been shown to be sufficiently deep to have contained ancient scrolls.

However, this may only indicate that the same slave held two positions in succession: "maintenance man of the baths" (vilicus thermarum) and "employee in the Greek library" (a bybliothecae Graecae).

If a rich Roman wished to gain the favour of the people, he might arrange for a free admission day in his name.

Where natural hot springs existed (as in Bath, England; Băile Herculane, Romania or Aquae Calidae near Burgas and Serdica, Bulgaria) thermae were built around them.

Alternatively, a system of hypocausta (from hypo 'below' and kaio 'to burn') were utilised to heat the piped water from a furnace (praefurnium).

In 1910, Pennsylvania Station was opened in New York City, with a Main Waiting Room that borrowed heavily from the frigidarium of the Baths of Diocletian, especially with the use of repeated groin vaults in the ceiling.