Titus

During his father's rule, Titus gained notoriety in Rome serving as prefect of the Praetorian Guard, and for carrying on a controversial relationship with the Jewish queen Berenice.

Despite concerns over his character, Titus ruled to great acclaim following the death of Vespasian on 23 June 79, and was considered a good emperor by Suetonius and other contemporary historians.

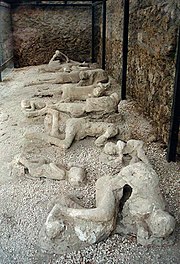

As emperor, Titus is best known for completing the Colosseum and for his generosity in relieving the suffering caused by two disasters, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 and a fire in Rome in 80.

[3] One such family was the gens Flavia, which rose from relative obscurity to prominence in only four generations, acquiring wealth and status under the Emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

[6] What little is known of Titus's early life has been handed down by Suetonius, who recorded that he was brought up at the imperial court in the company of Britannicus,[7] the son of Emperor Claudius, who would be murdered by Nero in 55.

[20] By 68, the entire coast and the north of Judaea were subjugated by the Roman Army, with decisive victories won at Taricheae and Gamala, where Titus distinguished himself as a skilled general.

[27] A strong force drawn from the Judaean and Syrian legions marched on Rome under the command of Mucianus, and Vespasian travelled to Alexandria, leaving Titus in charge to end the Jewish rebellion.

The Roman Army was joined by the Twelfth Legion, which had been previously defeated under Cestius Gallus, and from Alexandria, Vespasian sent Tiberius Julius Alexander, governor of Egypt, to act as Titus' second in command.

[32] Titus surrounded the city with three legions (Vth, XIIth and XVth) on the western side and one (Xth) on the Mount of Olives to the east.

He put pressure on the food and water supplies of the inhabitants by allowing pilgrims to enter the city to celebrate Passover and then refusing them egress.

When the fires subsided, Titus gave the order to destroy the remainder of the city, allegedly intending that no one would remember the name Jerusalem.

[43] Unable to sail to Italy during the winter, Titus celebrated elaborate games at Caesarea Maritima and Berytus and then travelled to Zeugma on the Euphrates, where he was presented with a crown by Vologases I of Parthia.

[46] Accompanied by Vespasian and Domitian, Titus rode into the city, enthusiastically saluted by the Roman populace and preceded by a lavish parade containing treasures and captives from the war.

Josephus describes a procession with large amounts of gold and silver carried along the route, followed by elaborate re-enactments of the war, Jewish prisoners and finally the treasures taken from the Temple of Jerusalem, including the Menorah and the Pentateuch.

[49] In addition to sharing tribunician power with his father, Titus held seven consulships during Vespasian's reign[50] and acted as his secretary, appearing in the Senate on his behalf.

[50] In that capacity, Titus achieved considerable notoriety in Rome for his violent actions, frequently ordering the execution of suspected traitors on the spot.

[59] Against those expectations, however, Titus proved to be an effective emperor and was well loved by the population, who praised him highly when they found that he possessed the greatest virtues, instead of vices.

[61] This led to numerous trials and executions under Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero, and the formation of networks of informers (delators), which terrorised Rome's political system for decades.

[62]Consequently, no senators were put to death during his reign;[62] he thus kept to his promise that he would assume the office of Pontifex Maximus "for the purpose of keeping his hands unstained".

[66] Titus appointed two ex-consuls to organise and coordinate the relief effort and personally donated large amounts of money from the imperial treasury to aid the victims of the volcano.

[60][67] Although the extent of the damage was not as disastrous as during the Great Fire of 64 and crucially spared the many districts of insulae, Cassius Dio records a long list of important public buildings that were destroyed, including Agrippa's Pantheon, the Temple of Jupiter, the Diribitorium, parts of the Theatre of Pompey, and the Saepta Julia among others.

[73] In addition to providing spectacular entertainments to the Roman populace, the building was also conceived as a gigantic triumphal monument to commemorate the military achievements of the Flavians during the Jewish Wars.

[75] During the games, wooden balls were dropped into the audience, inscribed with various prizes (clothing, gold or even slaves), which could then be traded for the designated item.

[82] Suetonius and Cassius Dio maintain that he died of natural causes, but both accuse Domitian of having left the ailing Titus for dead.

[72] The Babylonian Talmud (Gittin 56b) attributes Titus's death to an insect that flew into his nose and picked at his brain for seven years in a repetition of another legend referring to the biblical King Nimrod.

[86] Jewish tradition says that Titus was plagued by God for destroying the second Temple and died as a result of a gnat going up his nose, causing a large growth inside of his brain that killed him.

[87][88] A story is recorded in which Onkelos, a nephew of the Roman emperor Titus who destroyed the Second Temple, intent on converting to Judaism, summons up spirits to help make up his mind.

Suetonius Tranquilius gives a short but highly favourable account on Titus's reign in The Lives of Twelve Caesars, emphasising his military achievements and his generosity as emperor.

[94] Titus, of the same surname as his father, was the delight and darling of the human race; such surpassing ability had he, by nature, art, or good fortune, to win the affections of all men, and that, too, which is no easy task, while he was emperor.

He shares a similar outlook as Suetonius, possibly even using the latter as a source but is more reserved by noting that His satisfactory record may also have been due to the fact that he survived his accession but a very short time, for he was thus given no opportunity for wrongdoing.