Roman sculpture

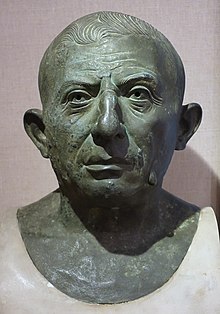

The strengths of Roman sculpture are in portraiture, where they were less concerned with the ideal than the Greeks or Ancient Egyptians, and produced very characterful works, and in narrative relief scenes.

While a great deal of Roman sculpture, especially in stone, survives more or less intact, it is often damaged or fragmentary; life-size bronze statues are much more rare as most have been recycled for their metal.

[1] Most statues were actually far more lifelike and often brightly colored when originally created; the raw stone surfaces found today is due to the pigment being lost over the centuries.

An Etruscan speciality was near life size tomb effigies in terracotta, usually lying on top of a sarcophagus lid propped up on one elbow in the pose of a diner in that period.

[9] The Romans did not generally attempt to compete with free-standing Greek works of heroic exploits from history or mythology, but from early on produced historical works in relief, culminating in the great Roman triumphal columns with continuous narrative reliefs winding around them, of which those commemorating Trajan (CE 113) and Marcus Aurelius (by 193) survive in Rome, where the Ara Pacis ("Altar of Peace", 13 BCE) represents the official Greco-Roman style at its most classical and refined.

[11] For a much wider section of the population, moulded relief decoration of pottery vessels and small figurines were produced in great quantity and often considerable quality.

Even the most important imperial monuments now showed stumpy, large-eyed figures in a harsh frontal style, in simple compositions emphasizing power at the expense of grace.

Ernst Kitzinger found in both monuments the same "stubby proportions, angular movements, an ordering of parts through symmetry and repetition and a rendering of features and drapery folds through incisions rather than modelling...

During the Roman Republic, it was considered a sign of character not to gloss over physical imperfections, and to depict men in particular as rugged and unconcerned with vanity: the portrait was a map of experience.

Roman altars were usually rather modest and plain, but some Imperial examples are modeled after Greek practice with elaborate reliefs, most famously the Ara Pacis, which has been called "the most representative work of Augustan art.

"[24] Small bronze statuettes and ceramic figurines, executed with varying degrees of artistic competence, are plentiful in the archaeological record, particularly in the provinces, and indicate that these were a continual presence in the lives of Romans, whether for votives or for private devotional display at home or in neighborhood shrines.

Sculptures recovered from the site of the Gardens of Sallust, opened to the public by Tiberius, include: Roman baths were another site for sculpture; among the well-known pieces recovered from the Baths of Caracalla are the Farnese Bull and Farnese Hercules and larger-than-life-sized early 3rd century patriotic figures somewhat reminiscent of Soviet Social Realist works (now in the Museo di Capodimonte, Naples).