Rose–Baley Party

John Udell, a 62-year-old Baptist minister kept a daily journal of the party's travels, recording the locations of their campsites, documenting their progress, and noting the availability of resources.

[3] The only other source of firsthand information is Rose, whose account was printed in the Missouri Republican in 1859, and later reprinted as an appendix in Dr. Robert Glass Cleland's work, The Cattle on a Thousand Hills: Southern California, 1850–1880.

[4] In October 1857, an expedition led by Edward Fitzgerald Beale was tasked with establishing a trade route along the 35th parallel from Fort Smith, Arkansas to Los Angeles, California.

[12] In 1892, writing in The Californian, he identified what motivated him to leave Iowa, where he had built several successful businesses: In 1858 some miners who had just returned from California so fired my imagination with descriptions of its glorious climate, wealth of flowers, and luscious fruits, that I was inspired with an irresistible desire to experience in person the delights to be found in the land of plenty.

[16] The resulting tensions between pro-slavery and anti-slavery groups fueled conflict near the Missouri state line, affecting its western counties, including Nodaway, where the Baleys and Hedgpeths lived.

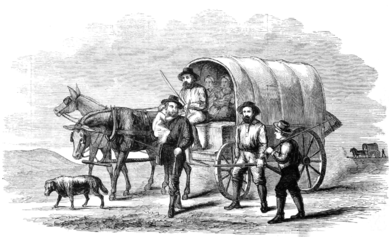

[17] The combined Baley-Hedgpeth outfits were led by a 44-year-old veteran of the Black Hawk War, Gillum Baley, and comprised eight Murphy wagons, 62 oxen, 75 head of cattle, and several riding horses.

[20] In the interests of safety, the groups agreed to an informal merger; their combined outfits numbered 20 wagons, 40 men, 50 to 60 women and children, and nearly 500 head of unbranded cattle.

The Cimarron Cutoff was 100 miles (160 km) shorter and easier to navigate with large wagons, but according to Baley it also led its travelers through the territory of the hostile Comanche and Kiowa people.

[11] Udell, writing in his journal, explained his concern: "I thought it was preposterous to start on so long a journey with so many woman and helpless children, and so many dangers attending the attempt.

Townspeople and army officers, including Benjamin Bonneville, encouraged them to take the new route, which was shorter than the established southern trails by 200 miles (320 km), or approximately 30 days travel.

[28]Beale suggested that, in addition to a military fort, the route was also in immediate need of bridges and dams to ensure safe travel and provide a reliable water supply; he requested US$100,000 to fund the improvements.

[30] According to Baley, U.S. Army officers stationed in Albuquerque insisted the emigrants hire Jose Manuel Savedra, a Mexican guide who had traveled with Beale during his initial survey of the route, and his interpreter, Petro.

"[35] On July 7, they camped near El Morro National Monument, then called Inscription Rock, and several members of the party, including Rose and Udell, carved their names into stone —a tradition dating back to 1605.

They spent several hours visiting and sightseeing, and the Zuni sold them cornmeal and vegetables, as this was the last such opportunity to purchase supplies until San Bernardino, approximately 500 miles (800 km) away.

They left Zuni Pueblo late that afternoon and entered unfamiliar territory that, until now, had only been traversed by Native Americans, explorers, mountain men, and Spanish missionaries.

[43] On July 18, Udell recorded that spirits were high amongst the Rose–Baley Party: "Our large company continue to be harmonious, friendly, and kind to each other ... General good health prevails ... Travel today, 10 miles (16 km), and 1,112 from the Missouri River.

[50] According to Baley, on July 29 Savedra informed the Rose–Baley Party, now camped near Leroux Springs, that the next reliable drinking water was seventy or 80 miles (130 km) away, and there would not be a closer source until the coming rainy season.

[52] Udell disagreed, "I contended that we had better travel on, for, with careful and proper treatment, we could get the stock through to water, and if we remain here until the rainy season, in all human probability our provisions would be exhausted, and we should parish with starvation.

Two days later, a man returned to camp and reported that a spring had been found 15 miles (24 km) west, but its supply was so sparse that it could not meet the needs of the entire wagon train at once.

After a thorough debate it was decided that, despite stern warnings from Army officers in Albuquerque against splitting into smaller groups, the best course of action was to divide the train in two and water their stock separately.

[59] The emigrants spent the next morning filling casks and preparing for travel; they left late that afternoon, and after having trekked continuously for nearly twenty-four hours arrived at Partridge Creek the next day.

That night a thunderstorm filled the creek with rainwater, further easing their concerns; however, after traveling 20 miles (32 km) the following day, they realized that the recent rainfalls has not reached that far, forcing them to make a dry camp on August 17.

[61] According to Rose, Savedra knew that the Mohave rarely ventured this far from their homelands, so they assumed the Hualapai had taken the animals, which were returned the following morning as the party camped at Peach Springs.

According to Baley, as they journeyed from their campsite at Peach Springs to the Colorado River more than 100 miles (160 km) away, they were almost continuously harassed by Natives, who sent arrows flying into their wagon train during the day and raided their camp at night.

Soon afterward, a small group of Mohave warriors approached and asked, in a combination of broken English and Spanish, how many people their wagon train included and whether they intended to permanently settle near the Colorado River.

The Mohave, who appeared friendly and had brought with them corn and melons, which they sold to the emigrants, were promised that the wagon train planned to travel through the region en route to their intended destination in Southern California.

By noon on August 28, Rose had reached a patch of cottonwood trees about one mile from the river, where their oxen were unhitched and allowed to join the loose stock racing towards the water.

That danger was averted, but many Mohave set about driving off and slaughtering several of the party's cattle before leaving the emigrants alone at their encampment, some two hundred yards from the river and 10 miles (16 km) away from the Baley company's mountain camp.

They were visited around noon by twenty-five warriors and a Mohave sub-chief, who heard their complaints about the killing of their livestock and assured them that no further depredations would occur, and that they could cross the Colorado as they pleased.

Having lost the element of surprise, three hundred warriors then let out war whoops as they shot arrows into the camp, mortally wounding Rose's foreman, Alpha Brown.