Wind power in the United Kingdom

[12] It's reported by industry experts TGS 4C Offshore that the UK is currently not on track to meet this target due to challenges within the permitting process, supply chain and strike prices, however with the recent change of government and allocation round 6 budget this could likely accelerate the build out to 2030.

[10] The world's first electricity generating wind turbine was a battery charging machine installed in July 1887 by Scottish academic James Blyth to light his holiday home in Marykirk, Scotland.

[15] It was in 1951 that the first utility grid-connected wind turbine to operate in the United Kingdom was built by John Brown & Company in the Orkney Islands.

[17] In 2007 the United Kingdom Government agreed to an overall European Union target of generating 20% of the EU's energy supply from renewable sources by 2020.

Siemens chose the Hull area on the east coast of England because it is close to other large offshore projects planned in coming years.

He pointed to the tumbling cost of green energy as evidence that wind and solar could supplant fossil fuels quicker than expected.

[52] An estimate of the theoretical maximum potential of the United Kingdom's offshore wind resource in all waters to 700 metres (2,300 ft) depth gives the average power as 2200 GW.

[57] The construction price for offshore windfarms has fallen by almost a third since 2012 while technology improved and developers think a new generation of even larger turbines will enable yet more future cost reductions.

[46] During 2022 an additional 3.2 GW of capacity was added with the commissioning of the Moray East, Triton Knoll and Hornsea Project Two wind farms.

It is expected the Crown Estate will announce multiple new leasing Rounds and increases to existing bidding areas throughout the 2020–2030 period to achieve the government's aim of 40 GW.

Scotland's sparsely populated, hilly and windy countryside became a popular area for developers and the United Kingdom's first 100 MW+ farm went operational in 2006 at Hadyard Hill in South Ayrshire.

This compares extremely unfavourably with other types of major applications, such as housing, retail outlets and roads, 70% of which are decided within the 13- to 16-week statutory deadline; for wind farms the rate is just 6%.

[citation needed] Approximately half of all wind farm planning applications, over 4 GW worth of schemes, have objections from airports and traffic control on account of their impact on radar.

In 2008 NATS en Route, the BWEA, the Ministry of Defence and other government departments signed a Memorandum of Understanding seeking to establish a mechanism for resolving objections and funding for more technical research.

These factors are in turn affected by issues such as location, turbine size and spacing and, for offshore windfarms, water depth and distance from shore.

[129] A review of financial accounts published by the Renewable Energy Foundation in 2020 showed that UK offshore windfarm capital costs rose steadily from 2002 to around 2013, before stabilising and perhaps falling slightly.

This picture has been confirmed by a comprehensive review of audited accounts data for UK offshore windfarms, which found that levelised costs rose from around £60–70/MWh for early projects, to around £140–160/MWh by 2010–13, before stabilising.

[130] However, in recent CfD auctions, strike prices as low as £39.65/MWh have been agreed for offshore wind projects, which has led to an assumption that there has been an equivalent reduction in the underlying costs.

[141] A statistical and econometric analysis of a majority of onshore and offshore windfarms built in the United Kingdom since 2002 with a capacity of more than 10MW has been performed by a former professor of the School of Economics at the University of Edinburgh on behalf of an anti wind power organisation.

Rather, capital and operating costs per MW have increased, the latter driven by higher than expected frequency of equipment failure and preventative maintenance associated with new generations of larger turbines.

If confirmed, this would require financial regulators to impose heavy risk weightings on loans to offshore wind farm operators, effectively making them too risky for pension funds and small investors.

[142] Wind-generated power is a variable resource, and the amount of electricity produced at any given point in time by a given plant will depend on wind speeds, air density and turbine characteristics (among other factors).

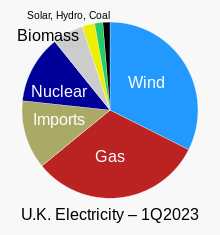

[143][150] The 2021 United Kingdom natural gas supplier crisis increased electricity prices,[151] which were further worsened by rising demand amidst a lack of wind.

[154] There is some dispute over the necessary amount of reserve or backup required to support the large-scale use of wind and solar energy due to the variable nature of its supply.

[159][160] In June 2011, several energy companies including Centrica told the government that 17 gas-fired plants costing £10 billion would be needed by 2020 to act as back-up generation for wind.

[citation needed] In 2015–2016, National Grid contracted 10 coal and gas-fired plants to keep spare capacity on standby for all generation modes, at a cost of £122 million, which represented 0.3% of an average electricity bill.

[170] A survey conducted in 2005 showed that 74% of people in Scotland agree that wind farms are necessary to meet current and future energy needs.

[176] Leo Murray of Possible (formerly 10:10 Climate Action) said, "It looks increasingly absurd that the Conservatives have effectively banned Britain's cheapest source of new power.

On 16 October 2014, TAG Energy Solutions announced the mothballing and semi closure of its Haverton Hill construction base near Billingham with between 70 and 100 staff redundancies after failing to secure any subsequent work following the order for 16 steel foundations for the Humber Estuary in East Yorkshire.

It hopes in the future to become a centre for excellence and has opened a skills academy to help re-train previous offshore workers for green energy projects.