Royal Indian Navy mutiny

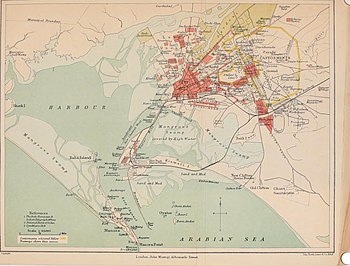

From the initial flashpoint in Bombay (now Mumbai), the revolt spread and found support throughout British India, from Karachi to Calcutta (now Kolkata), and ultimately came to involve over 10,000 sailors in 56 ships and shore establishments.

The leaders of the Congress were of the view that their idea of a peaceful culmination to a freedom struggle and smooth transfer of power would have been lost if an armed revolt succeeded with undesirable consequences.

The revolt was called off following a meeting between the President of the Naval Central Strike Committee (NCSC), M. S. Khan, and Vallab Bhai Patel of the Congress with a guarantee that none would be persecuted.

[6] The dissatisfaction among the Indian personnel came from a variety of causes such as dismal living conditions, arbitrary treatment, inadequate pay and a perception of an uncaring senior leadership.

The concentration of the personnel and grievances in its ranks combined with tense interracial relations and aspirations to end British rule in India led to a volatile situation in the navy.

In the post war period, he intended to preserve its status as a regional navy and had the vision for the RIN to serve as in instrument of British interests in the Indian Ocean.

According to the Home Department of the Raj, the Congress advocacy during the trials, their election campaign for the advisory council and the highlighting of excesses during the Quit India Movement contained inflammatory speeches and had created a volatile atmosphere.

[21] In late 1945, upon reassignment, around 20 operators along with a dozen sympathisers frustrated with racial discrimination faced by them during their period of service, formed a secretive group under the self designation of Azad Hind (transl.

Unable to catch the conspirators and restricted from taking strict action against their underlings, the command at HMIS Talwar resorted to increasing the pace of demobilization in the hopes that the troublemakers would be pushed out of the force during the process.

[26][27] The material was considered to be seditious; Dutt was interrogated by five senior officers in quick succession including a rear-admiral, he claimed responsibility for all acts of vandalism and announced his status as a political prisoner.

[10] On 17 February, a large number of ratings began refusing food and orders for military parades,[16] King had reportedly used the term "black bastards" to describe a group of sailors during the morning briefing.

[33] Rear Admiral Arthur Rullion Rattray, second–in–command to the Royal Indian Navy,[34] and the commanding officer at the Bombay Harbour conducted an inspection in person which confirmed that the unrest was widespread and beyond his control.

[34] The events at HMIS Talwar had motivated sailors across Bombay and the Royal Indian Navy to join in by the prospects of a revolution to overthrow the British Raj and in solidarity with the grievances of their naval fraternity.

[36] Demonstrations and agitations broke out in the city,[37] gasoline was seized from passing trucks, tramway tracks outside the Prince of Wales Museum were set on fire,[36] the US Information Office was raided and the American flag located inside was pulled down and burned on the streets.

In the afternoon of 19 February, the mutineers at the Bombay Harbour had congregated at HMIS Talwar to elect the Naval Central Strike Committee (NCSC) as their representatives and formulate the Charter of Demands.

[47] RIN trucks packed with naval ratings entered European–dominated commercial districts of Bombay shouting slogans to galvanize Indians, followed by instances of altercations between the mutineers and Europeans including servicemen.

[13] On 21 February 1946, Admiral John Henry Godfrey released a statement on the All India Radio, threatening the mutineers to surrender immediately or face complete destruction.

[54] He had conferred with the First Sea Lord (Chief of Naval Staff), Sir Andrew Cunningham who recommended the swift suppression of the mutiny to prevent it from turning into a greater military conflict.

The general body came to a unanimous decision to launch an agitation on 21 February with a procession beginning at the Keamari jetty on the mainland and eventually moving through the city in opposition to British rule and endorsing unity between the Indian National Congress and the All–India Muslim League.

[60] However, on 20 February 1946, before the planned procession could occur, a dozen naval ratings on the old sloop HMIS Hindustan disembarked from the ship and refused to return unless certain officers were transferred, in protest against discrimination faced by them.

The ratings working through the association, organised for walls in the naval areas and in the city to be struck with posters and painted with galvanising slogans such as "We shall live as a free nation" and "Tyrants your days are over", among others.

[67] In the morning of 22 February 1946, Commodore Curtis, the British commanding officer at the harbour held parley at 8:30 am, coming on board the ship in an effort to persuade the ratings to surrender, and providing "safe conduct" to those who would do so by 9:00 am.

[69] Altered by this development, the British troops advanced through Keamari and attempted to board HMIS Hindustan,[4] beginning with sniper fire from a distance directed at those on the deck of the ship.

[75] In the evening, the Communist Party of India held a public meeting at the Karachi Idgah park, which witnessed a gathering of around 1,000 people and was presided over by Sobho Gianchandani.

[80] On 23 February 1946, Karachi observed a complete shutdown with warehouses and stores closed,[78] tramway workers on strike,[81] and students from college and schools demonstrating on the streets.

The troops occupied the park in the afternoon, but the smaller groups, inflamed by their deployment, targeted government establishments such as post offices, police stations and the sole European–owned Grindlays Bank in the city.

[81] On 20 February 1946, it was reported that with the aid of radio and telegraph messages from the Signals School and Central Communications Office in Bombay, the mutiny had spread to all RIN sub stations in India, located at Madras, Cochin, Vizagapatam, Jamnagar, Calcutta and Delhi.

[86] Godfrey had issued a statement through the All India Radio giving the example of the shore establishment HMIS Valsura at Jamnagar for having the stayed loyal and threatening the destruction of the navy if the mutineers didn't surrender.

This may be Gandhi's (and the Congress's) conclusions from the Quit India Movement in 1942 when central control quickly dissolved under the impact of suppression by the colonial authorities, and localised actions, including widespread acts of sabotage, continued well into 1943.

It has been concluded by later historians that the discomfiture of the mainstream political parties was because the public outpourings indicated their weakening hold over the masses at a time when they could show no success in reaching agreement with the British Indian government.