Amazon rubber cycle

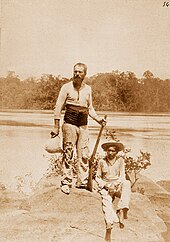

The Amazon rubber cycle or boom (Portuguese: Ciclo da borracha, Brazilian Portuguese: [ˈsiklu da buˈʁaʃɐ]; Spanish: Fiebre del caucho, pronounced [ˈfjeβɾe ðel ˈkawtʃo]) was an important part of the socioeconomic history of Brazil and Amazonian regions of neighboring countries, being related to the commercialization of rubber and the genocide of indigenous peoples.

Centered in the Amazon Basin, the boom resulted in a large expansion of colonization in the area, attracting immigrant workers and causing cultural and social transformations.

This process gives it superior mechanical properties, and causes it to lose its sticky character, and become stable – resistant to solvents and variations in temperature.

The rubber boom and the associated need for a large workforce had a significant negative effect on the indigenous population across Brazil, Bolivia, Venezuela, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia.

For the Indians in the Amazon's green 'ocean' in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, death was heralded by the arrival of steam launches or gunboats bearing armed men hungry for rubber.

Reclusive tribesmen living today in remote corners of the Peruvian selvas inherited the memory of a catastrophe proportional to the genocides of the Final Solution and the Armenian massacres.

[9][10][11][a] While writing in 1907, Charles R. Enock claimed that the Peruvian Government had, for a long time, been aware of the brutal exploitation of indigenous people by rubber merchants and collectors.

[17][18] Fuentes noted that many of the indigenous people in Peru were being killed during these correrias and in writing he referred to these raids as "the great crime of the mountain".

[20] The displacement and decimation of Conibo and Yine natives on the Ucayali and Urubamba River eventually led to the Asháninka demographic becoming the largest indigenous group in that region.

[29] An unknown number of their villages were destroyed,[30] and this region was never subjected to a systematic inquiry or investigation so the full extent of the devastation caused by the rubber boom in this area may never be known.

Elderly indigenous individuals were typically killed because they were unable to easily adapt to the new circumstances brought on by forced migrations and therefore they were viewed as disruptive elements.

[45][46] Roger Casement, an Irishman traveling the Putumayo region of Peru as a British consul from 1910 to 1911, documented the abuse, slavery, murder and use of stocks for torture against the natives: [47] The crimes charged against many men now in the employ of the Peruvian Amazon Company are of the most atrocious kind, including murder, violation, and constant flogging.According to Wade Davis, author of One River: The horrendous atrocities that were unleashed on the Indian people of the Amazon during the height of the rubber boom were like nothing that had been seen since the first days of the Spanish Conquest.During the first rubber boom in Colombia, natives from the Cofán, Siona, Oyo, Coreguaje, Macaguaje, Kichwa, Teteté, Huitoto, and other nations were indebted and exploited as a work force by various patrons.

[51] British minister Cecil Gosling stayed in the Suárez estates for five months, and referred to the labor system as "undisguised slavery.

This caused various people to travel to Brazil with the intention of learning more about the rubber tree and the process of latex extraction, from which they hoped to make their fortunes.

The Brazilian workers advanced further and further into the forests in the territory of Bolivia in search of new rubber trees for extraction, creating conflicts and skirmishes on the frontier towards the end of the 19th century.

Brazil was given possession of the region by Bolivia in exchange for territories in Mato Grosso, a payment of two million pounds sterling, and the compromise of constructing the railroad to connect to the Madeira River.

Thanks to rubber, the per capita income of Manaus was twice as much as the coffee-producing region (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo).

As payment for the export of rubber, the workers were paid in pounds sterling (£), the currency of the United Kingdom, which circulated in Manaus and Belém during this period.

Developers in Bolivia in 1846 began to promote the idea of constructing a railroad along the Madeira and Mamoré Rivers, to reach ports on the Atlantic Ocean for its export products.

The construction of the railroad began in 1907 during the government of Afonso Pena and was one of the most significant episodes in the history of the occupation of the Amazon, revealing the clear attempt to integrate it into the global marketplace via the commercialization of rubber.

[citation needed] Although the railroad and the cities of Porto Velho and Guajará-Mirim remained as a legacy to this bright economic period, the recession caused by the end of the rubber boom left profound scars on the Amazon region.

There was a massive loss of state tax income, high levels of unemployment, rural and urban emigration, and abandoned and unneeded housing.

[citation needed] To try to stem the crisis, the central government of Brazil created the Superintendência de Defesa da Borracha ("Superintendency of Defence of Rubber").

[citation needed] In the 1930s, Henry Ford, the United States automobile pioneer, undertook the cultivation of rubber trees in the Amazon region.

He established the city of Fordlândia in the west part of Pará state, specifically for this end, together with worker housing and planned community amenities.

The delegation of sovereignty by the national states allowed them to advance inter-state disputes and to eradicate or subordinate indigenous, up to then independent peoples from the Amazon to Tierra del Fuego.

After Fitzcarrald's drowned with his business partner Antonio Vaca Díez in the Urubamba river, his territories saw an increase in crime and abuse until the collapse of the holdings.

It set goals for the large-scale extraction of Amazon latex, an operation which became known as the Batalha da borracha ("rubber battle"), for the manpower and effort devoted to the project.

The international organization Rubber Development Corporation (RDC), financed with capital from United States industries, covered the expenses of relocating the migrants (known at the time os brabos).

The Brazilian government did not fulfill its promise to return the "rubber soldiers" to their homes at the end of the war as heroes and with housing comparable to that of the military veterans.