Stellar kinematics

Stellar-dynamical models of systems such as galaxies or star clusters are often compared with or tested against stellar-kinematic data to study their evolutionary history and mass distributions, and to detect the presence of dark matter or supermassive black holes through their gravitational influence on stellar orbits.

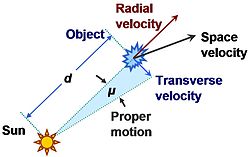

The component of stellar motion toward or away from the Sun, known as radial velocity, can be measured from the spectrum shift caused by the Doppler effect.

(Note that V is 7 km/s larger than estimated in 1998 by Dehnen et al.[6]) Stellar kinematics yields important astrophysical information about stars, and the galaxies in which they reside.

Stellar kinematics data combined with astrophysical modeling produces important information about the galactic system as a whole.

Both of these cases derive from the key fact that stellar kinematics can be related to the overall potential in which the stars are bound.

[12] Furthermore, Gaia's comprehensive dataset enabled the measurement of absolute proper motions in nearby dwarf spheroidal galaxies, serving as crucial indicators for understanding the mass distribution within the Milky Way.

[13] GAIA DR3 improved the quality of previously published data by providing detailed astrophysical parameters.

[14] While the complete GAIA DR4 is yet to be unveiled, the latest release offers enhanced insights into white dwarfs, hypervelocity stars, cosmological gravitational lensing, and the merger history of the Galaxy.

For example, the stars in the Milky Way can be subdivided into two general populations, based on their metallicity, or proportion of elements with atomic numbers higher than helium.

[19] A runaway star is one that is moving through space with an abnormally high velocity relative to the surrounding interstellar medium.

Tracing their motions back, their paths intersect near to the Orion Nebula about 2 million years ago.

Another example is the X-ray object Vela X-1, where photodigital techniques reveal the presence of a typical supersonic bow shock hyperbola.

Instead, the halo stars travel in elliptical orbits, often inclined to the disk, which take them well above and below the plane of the Milky Way.

Typical examples are the halo stars passing through the disk of the Milky Way at steep angles.

Most of these fast-moving stars are thought to be produced near the center of the Milky Way, where there is a larger population of these objects than further out.

Results from the second data release of Gaia (DR2) show that most high-velocity late-type stars have a high probability of being bound to the Milky Way.

[34] In March 2019, LAMOST-HVS1 was reported to be a confirmed hypervelocity star ejected from the stellar disk of the Milky Way.

[36][37][38][39][40] HVSs are believed to predominantly originate by close encounters of binary stars with the supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way.

One of the two partners is gravitationally captured by the black hole (in the sense of entering orbit around it), while the other escapes with high velocity, becoming a HVS.

In this scenario, a HVS is ejected from a close binary system as a result of the companion star undergoing a supernova explosion.

When it made its closest approach to the center of the Milky Way, some of its stars broke free and were thrown into space, due to the slingshot-like effect of the boost.

The stars formed within such a cloud compose gravitationally bound open clusters containing dozens to thousands of members with similar ages and compositions.

Groups of young stars that escape a cluster, or are no longer bound to each other, form stellar associations.

As the stars in a moving group formed in proximity and at nearly the same time from the same gas cloud, although later disrupted by tidal forces, they share similar characteristics.

Viktor Ambartsumian first categorized stellar associations into two groups, OB and T, based on the properties of their stars.

The Hipparcos satellite provided measurements that located a dozen OB associations within 650 parsecs of the Sun.

[17] Young stellar groups can contain a number of infant T Tauri stars that are still in the process of entering the main sequence.

[50] These young stellar groupings contain main sequence stars that are not sufficiently massive to disperse the interstellar clouds in which they formed.

The Banyan Σ tool[58] currently lists 29 nearby young moving groups[60][59] Recent additions to nearby moving groups are the Volans-Carina Association (VCA), discovered with Gaia,[61] and the Argus Association (ARG), confirmed with Gaia.

The Great Austral Young Association (GAYA) complex was found to be subdivided into the moving groups Carina, Columba, and Tucana-Horologium.