Runestone

The tradition of raising stones that had runic inscriptions first appeared in the 4th and 5th century, in Norway and Sweden, and these early runestones were usually placed next to graves,[2][3] though their precise function as commemorative monuments has been questioned.

[2] The tradition is mentioned in both Ynglinga saga and Hávamál: For men of consequence a mound should be raised to their memory, and for all other warriors who had been distinguished for manhood a standing stone, a custom that remained long after Odin's time.

A son is better, though late he be born, And his father to death have fared; Memory-stones seldom stand by the road Save when kinsman honors his kin.

Scores of chieftains and powerful Norse clans consciously tried to imitate King Harald, and from Denmark a runestone wave spread northwards through Sweden.

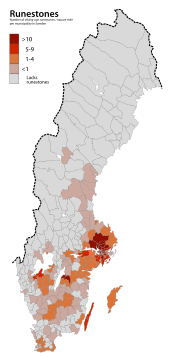

In most districts, the fad died out after a generation, but, in the central Swedish provinces of Uppland and Södermanland, the fashion lasted into the 12th century.

[11] Runestones were placed on selected spots in the landscape, such as assembly locations, roads, bridge constructions, and fords.

At this time, Swedish chieftains near Stockholm had created considerable fortunes through trade and pillaging both in the East and in the West.

[20] The main purpose of a runestone was to mark territory, to explain inheritance, to boast about constructions, to bring glory to dead kinsmen and to tell of important events.

It is not known why many people such as sisters, brothers, uncles, parents, housecarls, and business partners can be enumerated on runestones, but it is possible that it is because they are part of the inheritors.

[21] The first man who scholars know fell on the eastern route was the East Geat Eyvindr whose fate is mentioned on the 9th century Kälvesten Runestone.

[23] On the Smula Runestone in Västergötland, we are informed only that they died during a war campaign in the East: "Gulli/Kolli raised this stone in memory of his wife's brothers Ásbjôrn and Juli, very good valiant men.

[23][26] The country that is mentioned on the most runestones is the Byzantine Empire, which at the time comprised most of Asia Minor and the Balkans, as well as a part of Southern Italy.

The Anglo-Saxon rulers paid large sums, Danegelds, to Vikings, who mostly came from Denmark and who arrived to the English shores during the 990s and the first decades of the 11th century.

Ulf of Borresta who lived in Vallentuna travelled westwards several times,[30] as reported on the Yttergärde Runestone: And Ulfr has taken three payments in England.

[35][36] Other Vikings, such as Guðvér did not only attack England, but also Saxony, as reported by the Grinda Runestone in Södermanland:[37] Grjótgarðr (and) Einriði, the sons made (the stone) in memory of (their) able father.

"[40][41] A similar message is given on another runestone in Vallentuna near Stockholm that tells that two sons waited until they were on their death beds before they converted: "They died in (their) christening robes.

[39] Saint Michael, who was the leader of the army of Heaven, subsumed Odin's role as the psychopomp, and led the dead Christians to "light and paradise".

[39] There is also the Bogesund runestone that testifies to the change that people were no longer buried at the family's grave field: "He died in Eikrey(?).

Bragging was a virtue in Norse society, a habit in which the heroes of sagas often indulged, and is exemplified in runestones of the time.

A few examples will suffice: Other runestones, as evidenced in two of the previous three inscriptions, memorialize the pious acts of relatively new Christians.

For example, one reads: Although most runestones were set up to perpetuate the memories of men, many speak of women, often represented as conscientious landowners and pious Christians: as important members of extended families: and as much-missed loved ones: The only existing Scandinavian texts dating to the period before 1050[48] (besides a few finds of inscriptions on coins) are found amongst the runic inscriptions, some of which were scratched onto pieces of wood or metal spearheads, but for the most part they have been found on actual stones.

[48] The inscriptions seldom provide solid historical evidence of events and identifiable people but instead offer insight into the development of language and poetry, kinship, and habits of name-giving, settlement, depictions from Norse paganism, place-names and communications, Viking as well as trading expeditions, and, not least, the spread of Christianity.

These runic inscriptions coincide with certain Latin sources, such as the Annals of St. Bertin and the writings of Liudprand of Cremona, which contain valuable information on Scandinavians/Rus' who visited Byzantium.

The inscription itself is of a common kind that tells of the building of a bridge, but the ornamentation shows Sigurd sitting in a pit thrusting his sword, forged by Regin, through the body of the dragon, which also forms the runic band in which the runes are engraved.

[57] Two centuries later, the Icelander Snorri Sturluson would write: "The Midgarth Serpent bit at the ox-head and the hook caught in the roof of its mouth.

Then Thor got angry, assumed all his godly strength, and dug his heels so sturdily that his feet went right through the bottom of the boat and he braced them on the sea bed."

The stone may be an illustration of the giantess Hyrrokin ("fire-wrinkled"), who was summoned by the gods to help launch Baldr's funeral ship Hringhorni, which was too heavy for them.

One runestone in the church of Köping on Öland was discovered to be painted all over, and the colour of the words was alternating between black and red.

It also appears that the Vikings imported white lead, green malachite and blue azurite from Continental Europe.

One method to combat the lichen, algae and moss problem is to smear in fine-grained moist clay over the entire stone.