Russia in the First World War

The liberal bourgeoisie of the zemstvos, which had supported the war effort, became indignant; the industrialist Alexander Goutchkov led a campaign to denounce the negligence of the bureaucracy and the military leaders promoted by the favor of the Court.

[10] The discrediting of power and the economic crisis caused by the war against Japan led to the Russian Revolution of 1905, which first broke out in Saint Petersburg in January before spreading to the countryside:[11] around 3,000 manor houses of large landowners (15% of the total) were destroyed by peasants in 1905–1906.

[16] To counteract revolutionary currents, reactionary circles encouraged the creation of monarchist, anti-socialist, and anti-Semitic parties, the most important being the Union of the Russian People; these groups, known generically as the Black Hundreds, organized a series of pogroms from 1905 onwards.

In 1914, an editorialist in the Novoye Vremya newspaper wrote: "In the last twenty years, our western neighbor [Germany] has held the vital sources of our prosperity firmly in her fangs and, like a vampire, has sucked the blood of the Russian peasant".

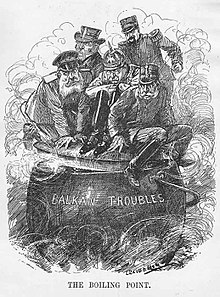

[20] However, Russia's educated circles were also concerned about Wilhelm II's global policy, which aimed to extend German military and colonial power around the world, and about that of Austria-Hungary, Germany's ally, with its ambitions in the Balkans.

[21] Aleksandr Guchkov, who had become chairman of the Duma's Defense Committee, supported a massive rearmament program, but made it conditional on a reform of the high command: he demanded that the Imperial Russian Navy staff be placed under the control of the government rather than the Court, and that promotions be based on merit rather than favor.

The arrival of the German cruisers Goeben and Breslau, which had taken refuge in the Turkish Straits from the Royal Navy, altered the balance of power in the Black Sea: Wilhelm II sold them, their crews, and commanders to the Sultan.

[46] Empress Alexandra, made very unpopular by her German origins and by the compromising favor she granted to the healer Grigori Rasputin, claimed to exercise power in an autocratic sense: on September 2, 1915, she obtained the suspension of the Duma, recently re-established, which led to two days of general strike in Petrograd.

[48] Towards the end of 1916, the parliamentary opposition formed several plots to depose the Tsar and entrust the regency to either his uncle Nicholas Nikolayevich or his younger brother Michael Alexandrovich, but neither of the two Grand Dukes had any desire to exercise power.

[49] At the beginning of 1916, when the British operation in the Dardanelles had turned into a fiasco, the Russians, supported by Armenian volunteers, decided to launch a major offensive on the Caucasus front: undertaken in the middle of winter in deep snow, it resulted in the capture of Erzurum, Trebizond and Erzincan.

He benefited from the efforts made since 1915 to renew his armament, with better machine-gun, artillery, and ammunition supplies, train several classes of new officers, and adapt his tactics based on the experience acquired by the Allies on the Western Front: support points and approach trenches enabled assault troops to advance as close as possible to enemy lines.

But the construction of the White Sea Railway was still unfinished at the start of the war: the new line, hastily built by unskilled workers, was single-track, partly made of wooden rails, and weakened by the instability of the frozen ground; it required constant repairs, and trains ran at 10 or 20 km/h.

[61] The priority given to military convoys bound for the front caused considerable delays in civilian transport to supply the major cities of northern Russia: food often rotted en route, due to a lack of locomotives.

The Union of Zemstvos, created on August 12, 1914 and chaired by Prince Georgi Lvov, federated provincial assemblies and rural landowners, organized food and equipment collections and set up care centers for the wounded.

[73] The Russian Red Cross (ROKK), thanks to its international influence and support among the ruling class, gained greater respect from the authorities and contributed to medical aid and the prevention of epidemics; on August 28, 1914, it set up a Central Bureau for Information on Prisoners of War, enabling families to re-establish contact with their missing loved ones.

[75] From 1915 onwards, the Empress, the princesses of the imperial family, court ladies, and actresses were all happy to be photographed in their nursing uniforms with the wounded; only Grand Duchess Olga, the Tsar's eldest daughter, seems to have been convincing in this role and enjoyed certain popularity.

[84] But as the defeats mounted, rumors spread of the existence of a "Black Bloc" comprising the Empress, Rasputin, and ministers of German origin such as Boris Stürmer, head of government in 1916, acting to sell Russia and conclude a separate peace with Germany.

Some of these exiles took part in the conference in Zimmerwald, a Swiss village that had become a meeting place for war opponents in Europe, but their audience in Russia was small: the Bolsheviks, decimated by arrests and emigration, had only 500 militants left in Petrograd at the end of 1914, and even fewer in other cities.

On March 14, amid a boisterous crowd of soldiers, he drew up Order No.1, calling on all units to elect committees and send their representatives to the soviet; at the same time, he abolished the outward signs of respect considered to be a relic of serfdom.

There was a lull in the movement during the summer, with heavy agricultural work and Kerensky's government taking relative control of the army and the courts, but the autumn saw a new outbreak of violence that the Bolsheviks would later interpret as a harbinger of proletarian revolution.

[136] Kerensky's optimism was sustained by the entry of the United States into the First World War, the Petrograd Soviet's rallying to the cause of national defense, the patriotic campaigns of the constitutional-democrats (liberal right), and the many admirers who saw in him the savior of Russia, called upon to play a decisive role in the victory of the democracies.

The Minister of Agriculture, Viktor Chernov, provisionally accepted the occupation of land by peasants, provoking indignation among the "bourgeois" members of the government, while the opening of negotiations with the Kiev Rada displeased Russian nationalists who feared secession from Ukraine.

On July 17, the Petrograd garrison and the sailors of the Kronstadt fleet, fearing to be sent to the front, join the striking workers of the Poutilov factories and rise up against the Provisional Government: they surround the Duma but, lacking Lenin's instructions, fail to seize power.

[155] Lenin, living underground in Petrograd after a brief exile in Finland, was determined to take advantage of the Provisional Government's weakness: he persuaded his comrades, Zinoviev, Kamenev and Trotsky, that power had to be seized by a coup de force before the Second All-Russian Congress of Workers' and Soldiers' Soviets, scheduled for early November, and the election of the Constituent Assembly in the same month, which would create a new legal order.

The Winter Palace, the last refuge of the Provisional Government, defended by a few cadets and women soldiers, surrendered after a few hours: the fighting seemed to involve only a small number of people, while restaurants, theaters and streetcars operated as usual.

On December 17, Trotsky issued an ultimatum to the Ukrainian Republic of Kiev, ordering it to allow the Red Guards free passage through its territory and to ban the Don Cossacks who left the front to return to their homeland.

In the autumn of 1918, seeing the German defeat approaching, Skoropadsky tried to draw closer to the Entente and the White Russians by promising to re-establish a federal union between Russia and Ukraine, but he was overthrown by the left-wing Ukrainian nationalists who retook Kiev.

[174] The Allies also sought to evacuate the Czechoslovak Legion via the Trans-Siberian Railway, but in May 1918 at Chelyabinsk, the Bolsheviks clumsily attempted to arrest and disarm the Legionaries, prompting them to join the White Army in the Russian Civil War.

[173] The "Reds" (Bolsheviks) managed to survive and triumph over their adversaries by establishing a centralized, authoritarian regime -war communism- which nationalized enterprises, strictly controlled trade and led expeditions into the countryside to confiscate crops.

[180] A former soldier turned Bolshevik cadre, Dimitri Oskine, describes the usual appearance of Russian cities:The stations were dead, trains rarely passed, at night there was no lighting, just a candle at the telegraph office.