Russian interregnum of 1825

Military governor Mikhail Miloradovich persuaded hesitant Nicholas to pledge allegiance to Constantine, who then lived in Warsaw as the viceroy of Poland.

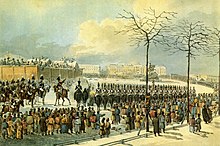

By noon the civil government and most of the troops of Saint Petersburg pledged allegiance to Nicholas but the Decembrists incited three thousand soldiers in support of Constantine and took a stand on Senate Square.

Korff wrote that Constantine's renunciation "was completed or, at all events, received its final arrangement" in the very end of 1821 when all four brothers reunited in Saint Petersburg.

[13] Filaret feared that a document locked in Moscow could not influence the transfer of power to the successor, which would normally take place in Saint Petersburg, and objected to Alexander.

The tsar reluctantly agreed and ordered Golitsyn to make three copies and deposit them in sealed envelopes in the Synod, the Senate and the State Council in Saint Petersburg.

[25] Economic downfall fuelled radical opposition inside the Russian nobility: "it was Alexander's failures to live up to their hopes that led them to take on the task themselves".

Instead of reducing the army to an affordable peacetime size, Alexander tried to cut spending through the establishment of self-sustaining military settlements, which failed "from start to finish".

In the same year Pavel Pestel, the most radical conspirator, relocated to Ukraine and began actively recruiting Army officers, the core of the future Southern Society.

[35] Members of the Northern Society indulged in writing elaborate aristocratic constitutions while Pestel and his ring settled on changing the regime by military force.

[36] Pestel's own political program, influenced by Antoine Destutt de Tracy, Adam Smith, Baron d'Holbach and Jeremy Bentham[37] envisioned "one nation, one government, one language" for the whole country, a uniform Russian-speaking entity with no concessions to ethnic or religious minorities, even the Finns or the Mongols.

[38] Contrary to the aspirations of the Northern Society, Pestel planned to reduce the influence of landed and financial aristocracy, "the main obstacle to national welfare that could be eliminated only under a republican form of government.

September 1], 1825[43] Alexander left Saint Petersburg to accompany the ailing Empress Elizabeth to spa treatment in Taganrog, then a "rather agreeable town"[44] on the coast of the Sea of Azov.

[48] The reunion in Taganrog, according to Volkonsky, became the couple's second honeymoon[47] (Wortman noted that this and similar sentimental opinions, influenced by Nicholas's propaganda, should not be taken literally[49]).

From this moment and until the outbreak of the Decembrist revolt Miloradovich maintained a confident demeanor and persuaded Nicholas that "the city is quiet and tranquil" despite mounting evidence to the contrary.

November 29], and informed governor Dmitry Golitsyn that Constantine was now Emperor, that the city administration must be sworn immediately and that "a certain packet which has been deposited in 1823 in the Cathedral" must remain sealed.

[78] He explained that a copy of Alexander's manifest, written by his own hand, was waiting for the occasion right there, in State Council files, and "bitterly deprecated the unnecessary precipitation in taking the oath".

Minister of Justice Lobanov-Rostovsky and admiral Shishkov opposed, insisting on the legality of oath to Constantine, but the majority temporarily leaned towards Golitsyn's stance.

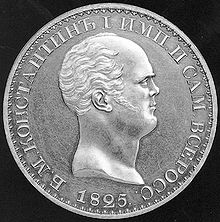

December 6], Minister of Finance Georg von Cancrin ordered minting of a new coin bearing the profile of Emperor and Autocrat Constantine.

Rumours and speculations made Michael's presence in the palace intolerable and the family council dominated by Empress Maria decided that he must return to Warsaw and personally persuade Constantine to come to Saint Petersburg.

Nicholas, still hoping to "conceal the whole affair in the closest secrecy" particularly from his mother, summoned Miloradovich and Alexander Golitsyn – the men who already earned his displeasure but whose offices were vital in maintaining order.

[101] He then summoned three key officials representing the Church, the Guards and the civil government, and ordered them to convene a State Council meeting at 8 p.m. of the next day.

[112] Decembrists were disorganized: their "dictator" Sergey Trubetskoy did not show up at all,[113] "the bravest men among the leaders developed an apathy and unwonted lack of nerve.

[115] Oath in the troops proceeded smoothly until the men of Horse Artillery Regiment demanded personal assurance from Grand Duke Michael.

[3] The Southern Society attempted their own revolt: one thousand men of the Chernigov Regiment led by Sergey Muravyov-Apostol and Mikhail Bestuzhev-Ryumin ravaged Ukrainian towns and evaded government troops until a defeat at Kovalivka on January 15 [O.S.

Hugh Seton-Watson wrote that it was "the first and the last political revolt by army officers"; Nicholas and his successors eradicated liberalism in the troops and secured their unconditional loyalty.

Five leaders were hanged, others exiled to Siberia;[128] Nicholas commuted most sentences in a demonstration of good will, sending the least offenders to fight as soldiers in the Caucasian War.

"[132] Contrary to Alexander's public image of a liberal conqueror, Nicholas chose to present himself as the defender of order, a distinctively Russian nationalist leader protecting the nation from foreign evils.

[100] Lack of public support encouraged Nicholas to stage grand ceremonial events; the whole reign was marked by sentimental "demonstrations of attachments and love" to the tsar "who had evoked only antipathy".

It was accepted in Imperial Russian (Schilder) and Soviet historiography (Militsa Nechkina) and in Western academia (Anatole Mazour, Vladimir Nabokov, Hugh Seton-Watson).

Historians, biographers and fiction authors sought alternative explanations of irrational events and named Alexander, Nicholas, Miloradovich and Empress Maria, alone or in various combinations, as the secret driving forces of the interregnum.