Serfdom in Russia

Contemporary legal documents, such as Russkaya Pravda (12th century onwards), distinguished several degrees of feudal dependency of peasants.

While another form of slavery in Russia, kholopstvo, was ended by Peter I in 1723,[1] serfdom (Russian: крепостное право, romanized: krepostnoye pravo) was abolished only by Alexander II's emancipation reform of 1861; nevertheless, in times past, the state allowed peasants to sue for release from serfdom under certain conditions, and also took measures against abuses of landlord power.

Serfdom was rare in Little Russia (parts of today's central Ukraine), other Cossack lands, the Urals and Siberia until the reign of Catherine the Great (r. 1762–1796), when it spread to Ukraine[citation needed]; noblemen began to send their serfs into Cossack lands in an attempt to harvest their extensive untapped natural resources.

The emperor and the highest state officials feared that the peasants' emancipation would be accompanied by popular unrest, given the reluctance of the landlords to lose their serf property, but took some actions to alleviate the situation of the peasantry.

[2] Emperor Alexander I (r. 1801–1825) wanted to reform the system but moved cautiously, liberating serfs in Estonia (1816), Livonia (1816), and Courland (1817) only.

In the mid-15th century the right of certain categories of peasants in some votchinas to leave their master was limited to a period of one week before and after Yuri's Day (November 26).

The Sudebnik of 1497 officially confirmed this time limit as universal for everybody and also established the amount of the "break-away" fee called pozhiloye (пожилое).

The legal code of Ivan III of Russia, Sudebnik (1497), strengthened the dependency of peasants, statewide, and restricted their mobility.

The Sudebnik of 1550 increased the amount of pozhiloye and introduced an additional tax called za povoz (за повоз, or transportation fee), in case a peasant refused to bring the harvest from the fields to his master.

These also defined the so-called fixed years (Урочные лета, urochniye leta), or the 5-year time frame for search of the runaway peasants.

In 1607, a new ukase defined sanctions for hiding and keeping runaways: the fine had to be paid to the state and pozhiloye – to the previous owner of the peasant.

The Sobornoye Ulozhenie (Соборное уложение, "Code of Law") of 1649 gave serfs to estates, and in 1658, flight was made a criminal offense.

The major landowners of the country, however, together with the dvoryane of the south, were interested in a short-term persecution due to the fact that many runaways would usually flee to the southern parts of Russia.

The Sobornoye Ulozhenie introduced an open-ended search for those on the run, meaning that all of the peasants who had fled from their masters after the census of 1626 or 1646–1647 had to be returned.

Between the end of Pugachev's Rebellion and the beginning of the 19th century, there were hundreds of outbreaks across Russia, and there was never a time when the peasantry was completely quiescent.

[13] Unlike serfs, state peasants and peasants under tsar's patronage were considered personally free, nobody had the right to sell them, to interfere in their family life, by law they were considered as 'free agricultural inhabitants' (Russ 'свободные сельские обыватели') One particular source of indignation in Europe was Kolokol published in London, England (1857–65) and Geneva (1865–67).

However, in 1822–23, due to changes in the domestic political course, Alexander I again forbade serfs to complain to the authorities about the cruelty of their masters, to bring lawsuits for emancipation, and also restored the right of landlords to exile peasants to Siberia at their discretion.

European philosophers during the Age of Enlightenment criticized serfdom and compared it to medieval labor practices which were almost non-existent in the rest of the continent.

[21] To discuss the peasant question, Nicholas I successively created 9 secret committees, issued about 100 decrees aimed at mitigating serfdom, but did not affect its foundations.

[25] According to certain Polish sources, increasingly in the 18th century Russian peasants were escaping from Russia to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (where once harsh serfdom conditions were improving) in significant enough numbers to become a major concern for the Russian Government and sufficient to play a role in its decision to partition the Commonwealth (one of the reasons Catherine II gave for the partition of Poland was the fact that thousands of peasants escaped from Russia to Poland to seek a better fate).

Jerzy Czajewski and Piotr Kimla wrote that until the partitions solved this problem, Russian armies raided territories of the Commonwealth, officially to recover the escapees, but in fact kidnapping many locals.

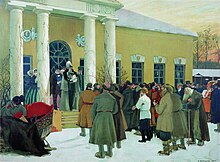

[32] In 1861, Alexander II freed all serfs (except in Georgia and Kalmykia[33]) in a major agrarian reform, stimulated in part by his view that "it is better to liberate the peasants from above" than to wait until they won their freedom by rising "from below".

[34] A 2018 study in the American Economic Review found "substantial increases in agricultural productivity, industrial output, and peasants' nutrition in Imperial Russia as a result of the abolition of serfdom in 1861".

After 1812 the rules relaxed slightly, but in order for a family to give their daughter to a husband in another estate they had to apply and present information to their landowner ahead of time.

If a serf wanted to marry a widow, then emancipation and death certificates were to be handed over and investigated for authenticity by their owner before a marriage could take place.

The groom's parents would be concerned about economical factors such as the size of the dowry as well as the bride's decency, modesty, obedience, ability to do work, and family background.

% peasants enserfed in each province, 1860 >55%: Kaluga Kyiv Kostroma Kutais Minsk Mogilev Nizhny Novgorod Podolia Ryazan Smolensk Tula Vitebsk Vladimir Volhynia Yaroslavl 36–55%: Chernigov Grodno Kovno Kursk Moscow Novgorod Oryol Penza Poltava Pskov Saratov Simbirsk Tambov Tver Vilna 16–35%: Don Ekaterinoslav Kharkov Kherson Kuban Perm Tiflis Vologda Voronezh In the Central Black Earth Region 70–77% of the serfs performed labour services (barshchina), the rest paid rent (obrok).

In literature, Russian serfdom provided both a backdrop and a source of dramatic tension for the works of prominent authors like Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Characters drawn from the serf population were portrayed with profound emotional depth, their stories shedding light on the harsh realities of serfdom.

These narratives served to amplify calls for social reform and underscored the deep inequalities of the Russian societal structure.