Rutherford scattering experiments

[10] In 1906, by studying how alpha particle beams are deflected by magnetic and electric fields, he deduced that they were essentially helium atoms stripped of two electrons.

Alpha particles are too tiny to see, but Rutherford knew about the Townsend discharge, a cascade effect from ionisation leading to a pulse of electric current.

On this principle, Rutherford and Geiger designed a simple counting device which consisted of two electrodes in a glass tube containing low pressure gas.

[9]: 261 The counter that Geiger and Rutherford built proved unreliable because the alpha particles were being too strongly deflected by their collisions with the molecules of air within the detection chamber.

The highly variable trajectories of the alpha particles meant that they did not all generate the same number of ions as they passed through the gas, thus producing erratic readings.

[2]: 247 The historian Silvan S. Schweber suggests that Rutherford's approach marked the shift to viewing all interactions and measurements in physics as scattering processes.

Eventually Bohr incorporated early ideas of quantum mechanics into the model of the atom, allowing prediction of electronic spectra and concepts of chemistry.

[9]: 304 Hantaro Nagaoka, who had proposed a Saturnian model of the atom, wrote to Rutherford from Tokyo in 1911: "I have been struck with the simpleness of the apparatus you employ and the brilliant results you obtain.

"[28] The astronomer Arthur Eddington called Rutherford's discovery the most important scientific achievement since Democritus proposed the atom ages earlier.

On consideration, I realised that this scattering backward must be the result of a single collision, and when I made calculations I saw that it was impossible to get anything of that order of magnitude unless you took a system in which the greater part of the mass of the atom was concentrated in a minute nucleus.

Geiger pumped all the air out of the tube so that the alpha particles would be unobstructed, and they left a neat and tight image on the screen that corresponded to the shape of the slit.

Rutherford suggested that Ernest Marsden, a physics undergraduate student studying under Geiger, should look for diffusely reflected or back-scattered alpha particles, even though these were not expected.

[9]: 264 These results where published in a 1909 paper, On a Diffuse Reflection of the α-Particles,[37] where Geiger and Marsden described the experiment by which they proved that alpha particles can indeed be scattered by more than 90°.

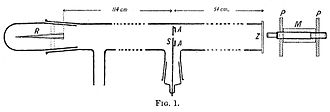

The alpha particles emitted from A was narrowed to a beam by a small circular hole at D. Geiger placed a metal foil in the path of the rays at D and E to observe how the zone of flashes changed.

[9]: 304 In a 1913 paper, The Laws of Deflexion of α Particles through Large Angles,[40] Geiger and Marsden describe a series of experiments by which they sought to experimentally verify Rutherford's equation.

Rutherford's equation predicted that the number of scintillations per minute s that will be observed at a given angle Φ should be proportional to:[18]: 11 Their 1913 paper describes four experiments by which they proved each of these four relationships.

A microscope (M) with its objective lens covered by a fluorescent zinc sulfide screen (S) penetrated the wall of the cylinder and pointed at the metal foil.

By turning the table, the microscope could be moved a full circle around the foil, allowing Geiger to observe and count alpha particles deflected by up to 150°.

[41] In a 1913 paper, Rutherford declared that the "nucleus" (as he now called it) was indeed positively charged, based on the result of experiments exploring the scattering of alpha particles in various gases.

He then proposes a model which will produce large deflections on a single encounter: place all of the positive charge at the centre of the sphere and ignore the electron scattering as insignificant.

The convention in Rutherford's time was to measure charge in electrostatic units, distance in centimeters, force in dynes, and energy in ergs.

To apply the hyperbolic trajectory solutions to the alpha particle problem, Rutherford expresses the parameters of the hyperbola in terms of the scattering geometry and energies.

[52]: 19 At the end of his development of the cross section formula, Rutherford emphasises that the results apply to single scattering and thus require measurements with thin foils.

The interaction only occurs in the relative coordinates, giving an equivalent one-body problem[46]: 58 just as Rutherford solved, but with different interpretations for the mass and scattering angle.

[56]: 191 Similar issues with smaller deviations for helium, magnesium, aluminium[57] led to the conclusion that the alpha particle was penetrating the nucleus in these cases.

[46]: 89 This section presents an alternative method to find the relation between the impact parameter and deflection angle in a single-atom encounter, using a force-centric approach as opposed to the energy-centric one that Rutherford used.

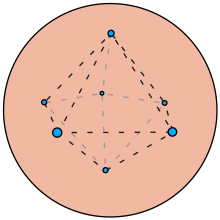

The scattering geometry is shown in this diagram[58][54]: 106 The impact parameter b is the distance between the alpha particle's initial trajectory and a parallel line that goes through the nucleus.

In his 1910 paper, Thomson presented the following equation (in this article's notation) that isolates the effect of the positive sphere in the plum pudding model on an incoming beta particle.

This shows that the largest possible deflection will be very small, to the point that the path of the alpha particle passing through the positive sphere of a gold atom is almost a straight line.

The convention in Rutherford's time was to measure charge in electrostatic units, distance in centimeters, force in dynes, and energy in ergs.

Right: What Geiger and Marsden observed was that a small fraction of the alpha particles experienced strong deflection.