SOFAR channel

[5][6][7] The deep sound channel was discovered and described independently by Maurice Ewing and J. Lamar Worzel at Columbia University and Leonid Brekhovskikh at the Lebedev Physics Institute in the 1940s.

[8][9] In testing the concept in 1944 Ewing and Worzel hung a hydrophone from Saluda, a sailing vessel assigned to the Underwater Sound Laboratory, with a second ship setting off explosive charges up to 900 nmi (1,000 mi; 1,700 km) away.

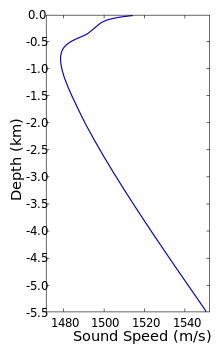

Other acoustic ducts exist, particularly in the upper mixed layer, but the ray paths lose energy with either surface or bottom reflections.

In the SOFAR channel, low frequencies, in particular, are refracted back into the duct so that energy loss is small and the sound travels thousands of miles.

[9][12][13] Analysis of Heard Island Feasibility Test data received by the Ascension Island Missile Impact Locating System hydrophones at an intermediate range of 9,200 km (5,700 mi; 5,000 nmi) from the source found "surprisingly high" signal-to-noise ratios, ranging from 19 to 30 dB, with unexpected phase stability and amplitude variability after a travel time of about 1 hour, 44 minutes and 17 seconds.

As the path turns northward, a station at 43º south, 16º east showed the profile reverting to the SOFAR type at 800 m (2,625 ft).

One such system deployed bottom moored sources off Cape Hatteras, off Bermuda and one on a seamount to send three precisely timed signals a day to provide approximately five-kilometre (3.1 mi; 2.7 nmi) accuracy.

The system detected seafloor spreading and magma events in the Juan de Fuca Ridge in time for research vessels to investigate.

As a result of that success, PMEL developed its own hydrophones for deployment worldwide to be suspended in the SOFAR channel by a float and anchor system.