SQUID

[2] For comparison, a typical refrigerator magnet produces 0.01 tesla (10−2 T), and some processes in animals produce very small magnetic fields between 10−9 T and 10−6 T. SERF atomic magnetometers, invented in the early 2000s are potentially more sensitive and do not require cryogenic refrigeration but are orders of magnitude larger in size (~1 cm3) and must be operated in a near-zero magnetic field.

There are two main types of SQUID: direct current (DC) and radio frequency (RF).

If a small external magnetic field is applied to the superconducting loop, a screening current,

, begins to circulate the loop that generates the magnetic field canceling the applied external flux, and creates an additional Josephson phase which is proportional to this external magnetic flux.

The current now flows in the opposite direction, opposing the difference between the admitted flux

Thus, the current changes direction periodically, every time the flux increases by additional half-integer multiple of

The voltage, in this case, is thus a function of the applied magnetic field and the period equal to

[8] The RF SQUID was invented in 1967 by Robert Jaklevic, John J. Lambe, Arnold Silver, and James Edward Zimmerman at Ford.

It is less sensitive compared to DC SQUID but is cheaper and easier to manufacture in smaller quantities.

Most fundamental measurements in biomagnetism, even of extremely small signals, have been made using RF SQUIDS.

[11] Depending on the external magnetic field, as the SQUID operates in the resistive mode, the effective inductance of the tank circuit changes, thus changing the resonant frequency of the tank circuit.

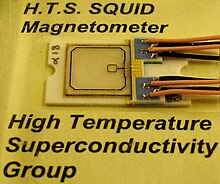

For a precise mathematical description refer to the original paper by Erné et al.[6][12] The traditional superconducting materials for SQUIDs are pure niobium or a lead alloy with 10% gold or indium, as pure lead is unstable when its temperature is repeatedly changed.

To maintain superconductivity, the entire device needs to operate within a few degrees of absolute zero, cooled with liquid helium.

[15] In 2006, A proof of concept was shown for CNT-SQUID sensors built with an aluminium loop and a single walled carbon nanotube Josephson junction.

Magnetoencephalography (MEG), for example, uses measurements from an array of SQUIDs to make inferences about neural activity inside brains.

Another area where SQUIDs are used is magnetogastrography, which is concerned with recording the weak magnetic fields of the stomach.

A novel application of SQUIDs is the magnetic marker monitoring method, which is used to trace the path of orally applied drugs.

Probably the most common commercial use of SQUIDs is in magnetic property measurement systems (MPMS).

These are turn-key systems, made by several manufacturers, that measure the magnetic properties of a material sample which typically has a temperature between 300 mK and 400 K.[20] With the decreasing size of SQUID sensors since the last decade, such sensor can equip the tip of an AFM probe.

Such device allows simultaneous measurement of roughness of the surface of a sample and the local magnetic flux.

The principle has been demonstrated by imaging human extremities, and its future application may include tumor screening.

The use of SQUIDs in oil prospecting, mineral exploration,[23] earthquake prediction and geothermal energy surveying is becoming more widespread as superconductor technology develops; they are also used as precision movement sensors in a variety of scientific applications, such as the detection of gravitational waves.

[24] A SQUID is the sensor in each of the four gyroscopes employed on Gravity Probe B in order to test the limits of the theory of general relativity.

[1] A modified RF SQUID was used to observe the dynamical Casimir effect for the first time.

[25][26] SQUIDs constructed from super-cooled niobium wire loops are used as the basis for D-Wave Systems 2000Q quantum computer.

Hundreds of thousands of multiplexed SQUIDs coupled to transition-edge sensors are presently being deployed to study the Cosmic microwave background, for X-ray astronomy, to search for dark matter made up of Weakly interacting massive particles, and for spectroscopy at Synchrotron light sources.

[28] A potential military application exists for use in anti-submarine warfare as a magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) fitted to maritime patrol aircraft.

[30][31] These nanoparticles are paramagnetic; they have no magnetic moment until exposed to an external field where they become ferromagnetic.

Measurement of the decaying magnetic field by SQUID sensors is used to detect and localize the nanoparticles.