SS California (1848)

One way around this prohibition was to heavily subsidize mail contracts since this duty traditionally belonged to the federal government.

Prior to 1848, Congress had already appropriated money to help subsidize mail steamers between Europe and the United States.

After disembarking from their paddle steamer on the Atlantic side, travelers ascended the Chagres River about 30 miles (48 km) by native canoes or dugouts before switching to mules to complete the roughly 60-mile (97-km) journey.

The U.S. Mail Steamship Company, headed by George Law, dispatched their first paddle steamer, the SS Falcon, from New York City on December 1, 1848, just before the discovery of gold in California was confirmed by President James K. Polk in his State of the Union speech on December 5 and the display of about $3,000 (~$85,503 in 2023) in gold at the War Department.

[2] The designs for oceangoing steamboats had already been worked out for regularly scheduled packet ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean between Le Havre, France, Liverpool, England and New York, Boston, and other U.S. cities.

Steamship designs were advanced in the United States but temporarily ignored in some shipyards in favor of the new very fast Clipper ships.

[3][4] California was built of choice oak and cedar, with her hull reinforced with diagonal iron straps to better withstand the pounding of her paddle wheels.

The wind was meant to be only an auxiliary or emergency source of power and she was expected to carry a head of steam at nearly all times while underway.

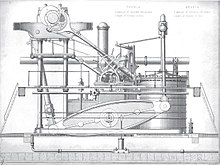

[5] California was powered by two 26-foot (7.9-m) diameter side paddle wheels driven by a large one-cylinder side-lever engine built by Novelty Iron Works of New York City.

Where fuel was cheap and easily obtainable, as on American rivers, the similar walking beam engine was used well into the 1890s.

Piston-cylinder lubrication was provided by allowing the steam to pick up a small amount of oil before being injected into the cylinder.

Since steamships required from 2 to 10 tons of coal per day, they were more expensive to run and had a maximum range of about 3,000 miles (4,800 km) before needing re-fueling.

A Clipper ship named Champion of the Seas traveled a record 465 nautical miles in 24 hours and the Flying Cloud set the world's sailing record for the fastest passage between New York City and San Francisco around Cape Horn - 89 days, 8 hours.

She left New York well before definite word of the California Gold Rush had reached the East Coast.

The combination of a larger load and the southbound California Current required more coal than she had picked up in Panama.

The new crew was much more expensive but the Panama City–San Francisco route was so potentially lucrative that the costs were simply deferred to the passengers in the price of a ticket.

Well-guarded gold shipments regularly went to Panama, took a well-escorted mule and canoe trip to the mouth of the Chagres River, and then caught another steamship to the East Coast, usually New York City.

These shipments and passengers helped pay for its construction and after it was built made its 47 miles (76 km) of track some of the most lucrative in the world.

As more steamers became available, a regular schedule for mail, passengers and cargo was a trip about every ten days to and from Panama City.

As the gold rush continued, the very lucrative San Francisco to Panama City route soon needed more and larger paddle steamers; ten more were eventually put into service.

This railroad made the sea routes via Panama very attractive, faster and reliable to travelers going to or from California even before it was completed in 1855.

The log of the SS California was originally published in the New Orleans Daily Picayune (February 23, 1849 Evening Edition).