Religious art

Buddhist art originated on the Indian subcontinent following the historical life of Siddhartha Gautama, 6th to 5th century BC, and thereafter evolved by contact with other cultures as it spread throughout Asia and the world.

The controversy over the use of graven images, the interpretation of the Second Commandment, and the crisis of Byzantine Iconoclasm led to a standardization of religious imagery within the Eastern Orthodoxy.

The Renaissance saw an increase in monumental secular works, but until the Protestant Reformation Christian art continued to be produced in great quantities, both for churches and clergy and for the laity.

However many modern artists such as Eric Gill, Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse, Jacob Epstein, Elisabeth Frink and Graham Sutherland have produced well-known works of art for churches.

[3] Through a social interpretation of Christianity, Fritz von Uhde also revived the interest in sacred art, through the depiction of Jesus in ordinary places in life.

The last part of the 20th and the first part of the 21st century have seen a focused effort by artists who claim faith in Christ to re-establish art with themes that revolve around faith, Christ, God, the Church, the Bible and other classic Christian themes as worthy of respect by the secular art world.

Other notable artists include Larry D. Alexander, Gary P. Bergel, Carlos Cazares, Bruce Herman, Deborah Sokolove, and John August Swanson.

While Confucian themes enjoyed representation in Chinese art centers, they are fewer in comparison to the number of artworks that are about or influenced by Daoism and Buddhism.

[7][8] Over time, the development of the Chinese writing system promoted the growth of calligraphy and visual arts in terms of social status.

[7] Hinduism, with its 1 billion followers, it makes up about 15% of the world's population and as such the culture that ensues it is full of different aspects of life that are effected by art.

Since religion and culture are inseparable with Hinduism recurring symbols such as the gods and their reincarnations, the lotus flower, extra limbs, and even the traditional arts make their appearances in many sculptures, paintings, music, and dance.

Persian miniatures, along with medieval depictions of Muhammad and angels in Islam, stand as prominent examples contrary to the modern Sunni tradition.

The strongest statements on the subject of figural depiction are made in the Hadith (Traditions of the Prophet), where painters are challenged to "breathe life" into their creations and threatened with punishment on the Day of Judgment.

The Qur'an is less specific but condemns idolatry and uses the Arabic term musawwir ("maker of forms", or artist) as an epithet for God.

Iconoclasm was previously known in the Byzantine period and aniconicism was a feature of the Judaic world, thus placing the Islamic objection to figurative representations within a larger context.

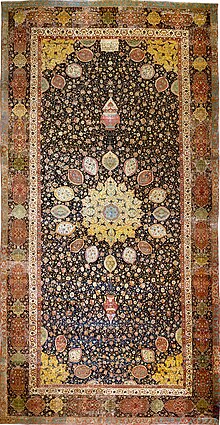

Arabesque is a decorative art style characterized by repetitive, intricate patterns of intertwined plants and abstract curvilinear motifs.

[15] Whether isolated or used in combination with non-figural ornamentation or figural representation, geometric patterns are popularly associated with Islamic art, largely due to their aniconic quality.

[15] These abstract designs not only adorn the surfaces of monumental Islamic architecture but also function as the major decorative element on a vast array of objects of all types.

[17] These abstract patterns are used as the primary ornamental feature on various items of all kinds, in addition to adorning the surfaces of massive Islamic buildings.

[18] Islamic artists incorporated significant components of the classical past to invent a new form of decoration that highlighted the vitality of order and unity.

The geometric shape of the circle is used in Islamic art to signify the fundamental symbol of oneness and the ultimate course of all diversity in creation.

[20] As the illustration below shows, many classic Islamic patterns have ritual beginnings in the circle's raw partition into regular sections.

The Alhambra palace in Spain and the Samarkand mosque in Uzbekistan are just two examples of the art of repeated geometric designs that can be seen worldwide.

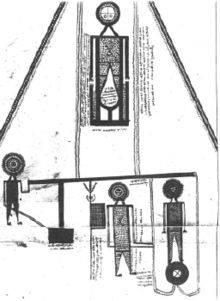

Mandaean scroll illustrations, usually labeled with lengthy written explanations, typically contain abstract geometric drawings of uthras that are reminiscent of cubism or prehistoric rock art.

[30] The early portraits of the Sikh Gurus and the elements in them, like their outfits, turbans, and poses, looked similar to Mughal nobles and princes.

[31] One of the first images of Guru Nanak depicts him as a pious, religious man with simple clothes and a rosary held in his hand, portraying his contemplative nature.

Further, with Guru Gobind Singh, elements of grandeur were added, such as royal attire, precious jewels, elegant shoes, a grand turban, and a warrior-like sword.

He was a great patron of art and architecture and sponsored the construction of many magnificent forts, palaces, temples, gurdwaras, precious jewels, clothes, colorful paintings, minting of coins and luxury tents and canopies.

[33] The most significant of these were the golden throne built by Hafez Muhammad Multani and the bejewelled canopy for the Guru Granth Sahib.

Under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, cities like Lahore, Amritsar, Multan, Sialkot, Srinagar and Patiala thrived as centres of the arts.