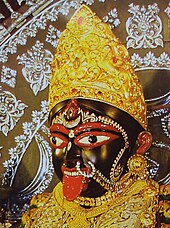

Kali

Traditional Kali (/ˈkɑːliː/; Sanskrit: काली, IAST: Kālī), also called Kalika, is a major goddess in Hinduism, primarily associated with time, death and destruction.

[5] Kali appears in many stories, with the most popular one being when she manifests as personification of goddess Durga's rage to defeat the demon Raktabija.

The terrifying iconography of Kali makes her a unique figure among the goddesses and symbolises her embracement and embodiment of the grim worldly realities of blood, death and destruction.

[14] According to Indologist Wendy Doniger, Kali's origins can be traced to the deities of the Pre-Vedic village, tribal, and mountain cultures of South Asia who were gradually appropriated and transformed by the Sanskritic traditions.

The deity of the first chapter of Devi Mahatmyam is Mahakali, who appears from the body of sleeping Vishnu as goddess Yoga Nidra to wake him up in order to protect Brahma and the world from two asuras (demons), Madhu-Kaitabha.

Kali's appearance is dark blue, gaunt with sunken eyes, wearing a tiger skin sari and a garland of human heads.

[10]: 221 In Kāli's most famous legend, Durga and her assistants, the Matrikas, wound the demon Raktabīja, in various ways and with a variety of weapons in an attempt to destroy him.

This episode is described in the Devi Mahatmyam, Kali is depicted as being fierce, clad in a tiger's skin and armed with a sword and noose.

She has deep, red eyes with tongue lolling out as she catches drops of Raktabīja's blood before they fall to the ground and create duplicates.

She is naked barring a grim set of ornamentation: "a necklace of skulls or freshly decapitated heads, a skirt of severed arms and jewellery made from the corpses of infants."

[2]: 399 The terrifying iconography of Kali is considered symbolic of her role as a protector and a bestower of freedom to devotees, of whom she shall take care of if they come to her in the "attitude of a child.

[2]: 399 In original depictions, Kali was often pictured in a cremation ground or battlefield standing on the corpse of Shiva, which symbolized her manifestation as Shakti.

[2] The Kalika Purana describes Kali as "possessing a soothing dark complexion, as perfectly beautiful, riding a lion, four-armed, holding a sword and blue lotus, her hair unrestrained, body firm and youthful".

The right hands are usually depicted in the abhaya (fearlessness) and varada (blessing) mudras, which means her initiated devotees (or anyone worshipping her with a true heart) will be saved as she will guide them here and in the hereafter.

[9]: 257 The Skanda Purana mentions that Kali took the form of Mahakali at the instruction of Shiva who wanted her to destroy the world during the time of universal destruction.

[26] According to Rachel Fell McDermott, the poets portrayed Shiva as "the devotee who falls at [Kali's] feet in devotion, in the surrender of his ego, or in hopes of gaining moksha by her touch."

In fact, Shiva is said to have become so enchanted by Kali that he performed austerities to win her, and having received the treasure of her feet, held them against his heart in reverence.

As a result, goddesses play an important role in the study and practice of Tantra Yoga and are essential in understanding the nature of reality.

[15]: 122–124 The Karpuradi-stotra also describes Kali's gentler form that is young, with a smiling face and with two right hands to dispel fear and offer boons.

[15]: 124–125 Kali is a central figure in late medieval Bengal devotional literature, with such notable devotee poets as Kamalakanta Bhattacharya (1769–1821) and Ramprasad Sen (1718–1775).

With the exception of being associated with Parvati as Shiva's consort, Kāli is rarely pictured in Hindu legends and iconography as a motherly figure until Bengali devotions beginning in the early eighteenth century.

Krodhakali, Kālikā, Krodheśvarī, Krishna Krodhini) is known as Tröma Nagmo (Classical Tibetan: ཁྲོ་མ་ནག་མོ་, Wylie: khro ma nag mo, English: "The Black Wrathful Lady").

[42] She is regarded as having seven forms; Bhadrakāli (who is associated with business and gold trade, and prominently worshipped at the Tamil Hindu Munneśvaram temple, though over 80% of its patrons are Sinhala Buddhists.

Bhadrakāli priests here interpret her tongue as symbolizing revenge, rather than embarrassment, and she tramples the demon of ignorance[42]), Mahābhadrakāli, Pēnakāli, Vandurukāli (Hanumāpatrakāli), Rīrikāli, Sohonkāli, and Ginikāli.

In 1998 McDermott wrote that feminists and New Age spiritualists are drawn to Kali because they perceive her to be a symbol of repressed female power, sexuality, and healing but that this is a misinterpretation which stems from a lack of knowledge about Hindu religious tradition.

She further stated that Kali enthusiasts since the early 1990s had sought to take on a more informed approach by incorporating more Indian perspective of her character than feminist and New Age interpretations.

[5] New age religious and spiritual movements have found in the iconographic representations and mythological stories of Kali an inspiration for theological and sexual liberation.

Therefore, Ra concocted a ruse whereby a plain was flooded with beer which had been dyed red, which Sekhmet mistook for blood and drank until she became too inebriated to continue killing, thus saving humanity from destruction.

[53] A 1939 American adventure film, Gunga Din, features a resurgent sect of Thuggees as worshippers of Kali who are at war with the British Raj.

[56][57] In Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), an action-adventure film which takes place in 1935, a Thuggee cult of Kali worshippers are villains.