St Augustine Gospels

"When this manuscript was made, Latin was still generally spoken, and Jerome [author of the Vulgate translation, of which this text is a copy], who died in 420, was then no more distant in time than (say) Walter Scott or Emily Brontë are to us.

[4] The main text is written in an Italian uncial hand which is widely accepted as dating to the 6th century – Rome or Monte Cassino have been suggested as the place of creation.

[7] In the late Middle Ages it was "kept not in the Library at Canterbury but actually lay on the altar; it belonged in other words, like a reliquary or the Cross, to Church ceremonial".

[9] The Augustine Gospels have also been taken to Canterbury for other major occasions: the visit of Pope John Paul II in 1982,[10] and the celebrations in 1997 for the 1,400th anniversary of the Gregorian mission.

A 1933 analysis of the St Augustine Gospels by Hermann Glunz documented around 700 variants from the standard Vulgate: most are minor differences of spelling or word order, but in some cases the scribe chooses readings from the Vetus Latina.

The same tendency is exhibited in the treatment of the architecture and ornament; the naturalistic polychrome accessories of a manuscript like the Vienna Dioscurides are flattened and attenuated into a calligraphic pattern.

It is clear from the variety of styles of evangelist portraits found in early Insular manuscripts, echoing examples known from the Continent, that other models were available, and there is a record of an illuminated and imported Bible of St Gregory at Canterbury in the 7th century.

He is shown sitting on a marble throne, with a cushion, in an elaborate architectural setting, probably based on the scaenae frons of a Roman theatre – a common convention for Late Antique miniatures, coins and Imperial portraiture.

The pose with the chin resting on a hand suggests an origin in classical author portraits of philosophers – more often evangelists are shown writing.

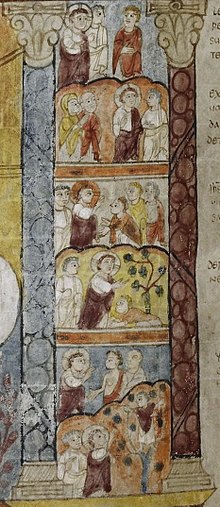

[23] More unusually, twelve small scenes drawn from Luke, mostly of the Works of Christ (who can be identified as the only figure with a halo), are set between columns in the architectural frame to the portrait.

The caption reads:"Ih[esu]s dixit vulpes fossa habent", a paraphrase of the start of Luke 9, 58 (and Matthew 8, 20): "et ait illi Iesus vulpes foveas habent et volucres caeli nidos Filius autem hominis non habet ubi caput reclinet" – "Jesus said to him: The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air nests: but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head."

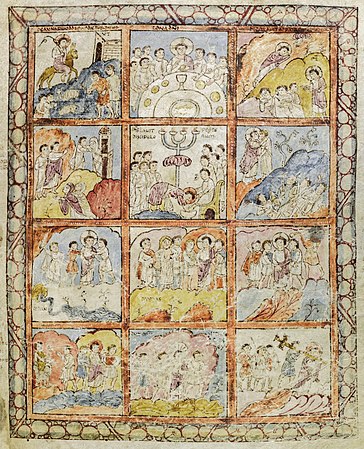

[33] A full-page miniature on folio 125r prior to Luke contains twelve narrative scenes from the Life of Christ, all from the Passion except the Raising of Lazarus.

[39] The difficulty of identifying many of the episodes of the Works from Luke demonstrates one of the reasons why scenes from the period of Christ's ministry became increasingly less common in medieval art.