Ephrem the Syrian

[4][5][6][7] Internal evidence from Ephrem's hymnody suggests that both his parents were part of the growing Christian community in the city, although later hagiographers wrote that his father was a pagan priest.

[8] In those days, religious culture in the region of Nisibis included local polytheism, Judaism and several varieties of the Early Christianity.

The city had a complex ethnic composition, consisting of "Assyrians, Arabs, Greeks, Jews, Parthians, Romans, and Iranians".

Ephrem is popularly credited as the founder of the School of Nisibis, which, in later centuries, was the centre of learning of the Church of the East.

Ephrem celebrated what he saw as the miraculous salvation of the city in a hymn that portrayed Nisibis as being like Noah's Ark, floating to safety on the flood.

[16] Ephrem, in his late fifties, applied himself to ministry in his new church and seems to have continued his work as a teacher, perhaps in the School of Edessa.

Edessa had been an important center of the Aramaic-speaking world, and the birthplace of a specific Middle Aramaic dialect that came to be known as the Syriac language.

[clarification needed] After a ten-year residency in Edessa, in his sixties, Ephrem succumbed to the plague as he ministered to its victims.

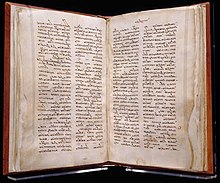

[18][19] Ephrem wrote exclusively in his native Aramaic language, using the local Edessan (Urhaya) dialect, that later came to be known as the Classical Syriac.

[8][20] Ephrem's works contain several endonymic (native) references to his language (Aramaic), homeland (Aram) and people (Arameans).

[26] In the early stages of modern scholarly studies, it was believed that some examples of the long-standing Greek practice of labeling Aramaic as "Syriac", that are found in the Cave of Treasures,[27][28] can be attributed to Ephrem, but later scholarly analyses have shown that the work in question was written much later (c. 600) by an unknown author, thus also showing that Ephrem's original works still belonged to the tradition unaffected by exonymic (foreign) labeling.

[29][30][31][32] One of the early admirers of Ephrem's works, theologian Jacob of Serugh (d. 521), who already belonged to the generation that accepted the custom of a double naming of their language not only as Aramaic (Ārāmāyā) but also as "Syriac" (Suryāyā),[33][34][35][36] wrote a homily (memrā) dedicated to Ephrem, praising him as the crown or wreath of the Arameans (Classical Syriac: ܐܳܪܳܡܳܝܘܬܐ), and the same praise was repeated in early liturgical texts.

[37][38] Only later, under the Greek influence already prevalent in the works of the middle fifth century author Theodoret of Cyrus,[39] did it became customary to associate Ephrem with Syriac identity, and label him only as "the Syrian" (Koinē Greek: Ἐφραίμ ὁ Σῦρος), thus blurring his Aramaic self-identification, attested by his own writings and works of other Aramaic-speaking writers, and also by examples from the earliest liturgical tradition.

During the process of critical editing and translation of sources within Syriac studies, some scholars have practiced various forms of arbitrary (and often unexplained) interventions, including the occasional disregard for the importance of original terms, used as endonymic (native) designations for Arameans and their language (ārāmāyā).

In previously mentioned memrā, dedicated to Ephrem, one of the terms for Aramean people (Classical Syriac: ܐܳܪܳܡܳܝܘܬܐ / Arameandom) was published correctly in original script of the source,[40] but in the same time it was translated in English as "Syriac nation",[41] and then enlisted among quotations related to "Syrian/Syriac" identity,[42] without any mention of Aramean-related terms in the source.

[49] Ephrem combines in his writing a threefold heritage: he draws on the models and methods of early Rabbinic Judaism, he engages skillfully with Greek science and philosophy, and he delights in the Mesopotamian/Persian tradition of mystery symbolism.

These hymns are full of rich, poetic imagery drawn from biblical sources, folk tradition, and other religions and philosophies.

[52] By the year 2000, English translations had been published for the following:[53] Some of these titles do not do justice to the entirety of the collection (for instance, only the first half of the Carmina Nisibena is about Nisibis).

He lamented that the faithful were "tossed to and fro and carried around with every wind of doctrine, by the cunning of men, by their craftiness and deceitful wiles" (Eph 4:14).

The Hymns Against Heresies employ colourful metaphors to describe the Incarnation of Christ as fully human and divine.

[citation needed] The most complete, critical text of writings attributed to Ephrem was compiled between 1955 and 1979 by Dom Edmund Beck, OSB, as part of the Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium (CSCO).

[56] Unlike in Europe, where the Nativity of Jesus was celebrated on 25 December, but the baptism of Jesus would evolve into a separate feast called "Epiphany" on 6 January, there was only one Christian feast celebrated in winter in the time and place where Ephrem lived, namely the Nativity on 6 January, when baptism was also performed.

[59] The relationship between Ephrem's compositions and femininity is shown again in documentation suggesting that the madrāšê were sung by all-women choirs with an accompanying lyre.

These women's choirs were composed of members of the Daughters of the Covenant, an important institution in historical Syriac Christianity, but they weren't always labeled as such.

[64] Ephrem's meditations on the symbols of Christian faith and his stand against heresy made him a popular source of inspiration throughout the church.

[citation needed] Syriac churches still use many of Ephrem's hymns as part of the annual cycle of worship.

[citation needed] Another one of the works attributed to Ephrem was the Cave of Treasures, written in Syriac, but by a much later, unknown author, who lived at the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century.

[66] Ephrem is attributed with writing hagiographies such as The Life of Saint Mary the Harlot (extant in Greek and Latin), though this credit is called into question.

[67] The best known of these writings is the Prayer of Saint Ephrem, which is recited at every service during Great Lent and other fasting periods in Eastern Christianity.

[citation needed] Also attributed to Ephrem are the Parenesis or "precepts", found in the 10th-century Rila fragments and the early 13th-century Kyiv Caves Patericon, translated into Old Church Slavonic.