Salem witch trials

[2] The Salem witch trials only came to an end when serious doubts began to arise among leading clergymen about the validity of the spectral evidence that had been used to justify so many of the convictions, and due to the sheer number of those accused, "including several prominent citizens of the colony".

In America, Salem's events have been used in political rhetoric and popular literature as a vivid cautionary tale about the dangers of isolation, religious extremism, false accusations, and lapses in due process.

[15] The trials began after a few local women in Salem Village were accused of witchcraft by four young girls, Betty Parris (9), Abigail Williams (11), Ann Putnam Jr. (12), and Elizabeth Hubbard (17).

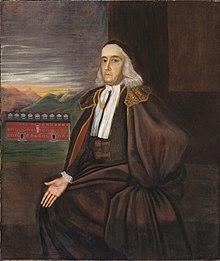

[19] The original 1629 Royal Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was vacated in 1684,[20] after which King James II installed Sir Edmund Andros as the governor of the Dominion of New England.

At the same time, tensions erupted between English colonists settling in "the Eastward" (the present-day coast of Maine) and French-supported Wabanaki people of that territory in what came to be known as King William's War.

[26] One of the first orders of business for the new governor and council on May 27, 1692, was the formal nomination of county justices of the peace, sheriffs, and the commission of a Special Court of Oyer and Terminer to handle the large numbers of people who were "thronging" the jails.

He did not seem able to settle his new parishioners' disputes: by deliberately seeking out "iniquitous behavior" in his congregation and making church members in good standing suffer public penance for small infractions, he contributed significantly to the tension within the village.

[41] The girls screamed, threw things about the room, uttered strange sounds, crawled under furniture, and contorted themselves into peculiar positions, according to the eyewitness account of Reverend Deodat Lawson, a former minister in Salem Village.

[52] When Sarah Cloyce (Nurse's sister) and Elizabeth (Bassett) Proctor were arrested in April, they were brought before John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin at a meeting in Salem Town.

On April 30, Reverend George Burroughs, Lydia Dustin, Susannah Martin, Dorcas Hoar, Sarah Morey, and Philip English (Mary's husband) were arrested.

Until this point, all the proceedings were investigative, but on May 27, 1692, William Phips ordered the establishment of a Special Court of Oyer and Terminer for Suffolk, Essex and Middlesex counties to prosecute the cases of those in jail.

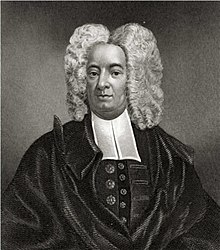

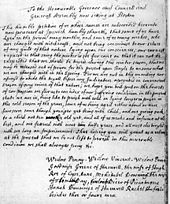

[54] Cotton Mather wrote to one of the judges, John Richards, a member of his congregation, on May 31, 1692,[55] expressing his support of the prosecutions, but cautioning him: [D]o not lay more stress on pure spectral evidence than it will bear [...] It is very certain that the Devils have sometimes represented the Shapes of persons not only innocent, but also very virtuous.

[56]The Court of Oyer and Terminer convened in Salem Town on June 2, 1692, with William Stoughton, the new Lieutenant Governor, as Chief Magistrate, Thomas Newton as the Crown's Attorney prosecuting the cases, and Stephen Sewall as clerk.

"[58][59] Their collective response came back dated June 15 and composed by Cotton Mather: Thomas Hutchinson sums the letter, "The two first and the last sections of this advice took away the force of all the others, and the prosecutions went on with more vigor than before."

VII) More people were accused, arrested and examined, but now in Salem Town, by former local magistrates John Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin, and Bartholomew Gedney, who had become judges of the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

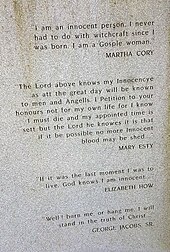

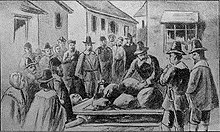

On September 19, 1692, Giles Corey refused to plead at trial, and was killed by peine forte et dure, a form of torture in which the subject is pressed beneath an increasingly heavy load of stones, in an attempt to make him enter a plea.

[77] His refusal to plead is usually explained as a way of preventing his estate from being confiscated by the Crown, but, according to historian Chadwick Hansen, much of Corey's property had already been seized, and he had made a will in prison: "His death was a protest [...] against the methods of the court".

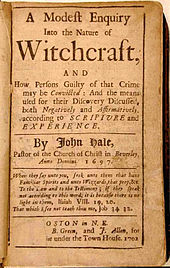

[84] Robert Calef, a strong critic of Cotton Mather, stated in his own book titled More Wonders of the Invisible World that by confessing, an accused would not be brought to trial, such as in the cases of Tituba and Dorcas Good.

Lawson's account describes this cake "a means to discover witchcraft" and provides other details such as that it was made from rye meal and urine from the afflicted girls and was fed to a dog.

He stated that while "calamities" that had begun in his own household "it never brake forth to any considerable light, until diabolical means were used, by the making of a cake by my Indian man, who had his direction from this our sister, Mary Sibley."

[92] A variety of secondary sources, starting with Charles W. Upham in the 19th century, typically relate that a circle of the girls, with Tituba's help, tried their hands at fortune telling.

But the record of Tituba's pre-trial examination holds her giving an energetic confession, speaking before the court of "creatures who inhabit the invisible world", and "the dark rituals which bind them together in service of Satan", implicating both Good and Osborne while asserting that "many other people in the colony were engaged in the devil's conspiracy against the Bay.

[42] Simultaneous with Lawson, William Milbourne, a Baptist minister in Boston, publicly petitioned the General Assembly in early June 1692, challenging the use of spectral evidence by the Court.

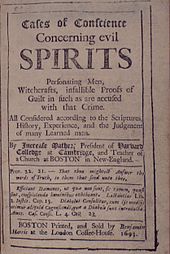

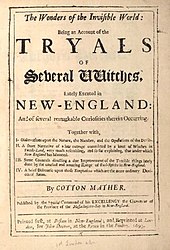

[100] The most famous primary source about the trials is Cotton Mather's Wonders of the Invisible World: Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches, Lately Executed in New-England, printed in October 1692.

In it, two characters, S (Salem) and B (Boston), discuss the way the proceedings were being conducted, with "B" urging caution about the use of testimony from the afflicted and the confessors, stating, "whatever comes from them is to be suspected; and it is dangerous using or crediting them too far".

The General Court initially reversed the attainder only for those who had filed petitions,[117] only three people who had been convicted but not executed: Abigail Faulkner Sr., Elizabeth Proctor and Sarah Wardwell.

In 1957, descendants of the six people who had been wrongly convicted and executed but who had not been included in the bill for a reversal of attainder in 1711, or added to it in 1712, demanded that the General Court formally clear the names of their ancestral family members.

After extensive efforts by Paula Keene, a Salem schoolteacher, state representatives J. Michael Ruane and Paul Tirone, along with others, issued a bill whereby the names of all those not previously listed were to be added to this resolution.

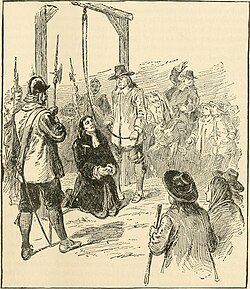

[132] In January 2016, the University of Virginia announced its project team had determined the execution site on Gallows Hill in Salem, where nineteen "witches" had been hanged in public.

Various medical and psychological explanations for the observed symptoms have been explored by researchers, including psychological hysteria in response to Indian attacks, convulsive ergotism caused by eating rye bread made from grain infected by the fungus Claviceps purpurea (a natural substance from which LSD is derived),[136] an epidemic of bird-borne encephalitis lethargica, and sleep paralysis to explain the nocturnal attacks alleged by some of the accusers.