Sea level rise

Managed retreat, accommodating coastal change, or protecting against sea level rise through hard-construction practices like seawalls[18] are hard approaches.

[35][39][40] This theory had been highly influential – in a 2020 survey of 106 experts, the 2016 paper which suggested 1 m (3+1⁄2 ft) or more of sea level rise by 2100 from Antarctica alone,[26] was considered even more important than the 2014 IPCC Fifth Assessment Report.

[42] Marine ice cliff instability had also been very controversial, since it was proposed as a modelling exercise,[37] and the observational evidence from both the past and the present is very limited and ambiguous.

[44] So far, only one episode of seabed gouging by ice from the Younger Dryas period appears truly consistent with this theory,[45] but it had lasted for an estimated 900 years,[45] so it is unclear if it supports rapid sea level rise in the present.

[47][48][49][43] Due to these uncertainties, some scientists – including the originators of the hypothesis, Robert DeConto and David Pollard – have suggested that the best way to resolve the question would be to precisely determine sea level rise during the Last Interglacial.

In the worst estimated scenario, SSP-8.5 with ice cliff instability, the projected range for total sea level rise was 9.5–16.2 metres (31–53 ft) by the year 2300.

(Negative values represent the extremely low probability of large climate change-induced increases in precipitation greatly elevating ice sheet surface mass balance.

Continued carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel sources could cause additional tens of metres of sea level rise, over the next millennia.

[59] Burning of all fossil fuels on Earth is sufficient to melt the entire Antarctic ice sheet, causing about 58 m (190 ft) of sea level rise.

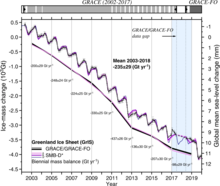

Over a consistent time period, assessments can attribute contributions to sea level rise and provide early indications of change in trajectory.

)[72] By 2018, data collected by Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) had shown that the global mean sea level was rising by 3.2 mm (1⁄8 in) per year.

In the recent geological past, thermal expansion from increased temperatures and changes in land ice are the dominant reasons of sea level rise.

Other factors affecting sea level rise include changes in snow mass, and flow from terrestrial water storage, though the contribution from these is thought to be small.

[35] Their disappearance would take at least several centuries, but is considered almost inevitable, as their bedrock topography deepens inland and becomes more vulnerable to meltwater, in what is known as marine ice sheet instability.

[84][85] Once ice loss from the West Antarctica is triggered, the only way to restore it to near-present values is by lowering the global temperature to 1 °C (1.8 °F) below the preindustrial level.

[108] Other researchers suggested that a climate engineering intervention to stabilize the ice sheet's glaciers may delay its loss by centuries and give more time to adapt.

One way to do this in theory would be large-scale carbon dioxide removal, but there would still be cause of greater ice losses and sea level rise from Greenland than if the threshold was not breached in the first place.

[141] Observational and modelling studies of mass loss from glaciers and ice caps show they contribute 0.2–0.4 mm per year to sea level rise, averaged over the 20th century.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres warned in 2023 that sea level rise risks causing human migrations on a "biblical scale".

[161][162] Starting around 2050, some nesting sites in Florida, Cuba, Ecuador and the island of Sint Eustatius for leatherback, loggerhead, hawksbill, green and olive ridley turtles are expected to be flooded.

[168][169][170][171] Both mangroves and tidal marshes protect against storm surges, waves and tsunamis, so their loss makes the effects of sea level rise worse.

[178] Scientists have linked extreme regional sea level rise on the US Northeast Coast to the downturn of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC).

[188][189] Some experts argue that retreat from the coast would have a lower impact on the GDP of India and Southeast Asia then attempting to protect every coastline, in the case of very high sea level rise.

[158] Across sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, damage from sea level rise could reach 2–4% of GDP by 2050, although this depends on the extent of future economic growth and climate change adaptation.

Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam alone account for 70% of people exposed to sea level rise during the 21st century.

Nine of these are the so-called sinking cities, where subsidence (typically caused by unsustainable groundwater extraction in the past) would compound sea level rise.

Because of its complex geography, the authorities chose a flexible mix of hard and soft measures to cope with sea level rise of over 1 meter per century.

In Mexico, damage from SLR to tourism hotspots like Cancun, Isla Mujeres, Playa del Carmen, Puerto Morelos and Cozumel could amount to US$1.4–2.3 billion.

[228][229] Five of the Solomon Islands have already disappeared due to the effects of sea level rise and stronger trade winds pushing water into the Western Pacific.

[230] Adaptation to sea level rise is costly for small island nations as a large portion of their population lives in areas that are at risk.