Weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals (as well as wood and artificial materials) through contact with water, atmospheric gases, sunlight, and biological organisms.

It occurs in situ (on-site, with little or no movement), and so is distinct from erosion, which involves the transport of rocks and minerals by agents such as water, ice, snow, wind, waves and gravity.

Water is the principal agent behind both kinds,[1] though atmospheric oxygen and carbon dioxide and the activities of biological organisms are also important.

Physical weathering involves the breakdown of rocks into smaller fragments through processes such as expansion and contraction, mainly due to temperature changes.

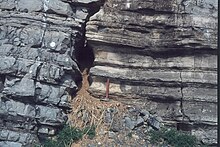

For example, cracks extended by physical weathering will increase the surface area exposed to chemical action, thus amplifying the rate of disintegration.

It was long believed that the most important of these is frost wedging, which is the widening of cracks or joints in rocks resulting from the expansion of porewater when it freezes.

[11] Frost wedging is most effective where there are daily cycles of melting and freezing of water-saturated rock, so it is unlikely to be significant in the tropics, in polar regions or in arid climates.

This premelted liquid layer has unusual properties, including a strong tendency to draw in water by capillary action from warmer parts of the rock.

This results in growth of the ice grain that puts considerable pressure on the surrounding rock,[12] up to ten times greater than is likely with frost wedging.

Thermal stress weathering is an important mechanism in deserts, where there is a large diurnal temperature range, hot in the day and cold at night.

[15] The importance of thermal stress weathering has long been discounted by geologists,[5][9] based on experiments in the early 20th century that seemed to show that its effects were unimportant.

These experiments have since been criticized as unrealistic, since the rock samples were small, were polished (which reduces nucleation of fractures), and were not buttressed.

These small samples were thus able to expand freely in all directions when heated in experimental ovens, which failed to produce the kinds of stress likely in natural settings.

Here the differential stress directed toward the unbuttressed surface can be as high as 35 megapascals (5,100 psi), easily enough to shatter rock.

Lichens and mosses grow on essentially bare rock surfaces and create a more humid chemical microenvironment.

[20] On a larger scale, seedlings sprouting in a crevice and plant roots exert physical pressure as well as providing a pathway for water and chemical infiltration.

Despite a slower reaction kinetics, this process is thermodynamically favored at low temperature, because colder water holds more dissolved carbon dioxide gas (due to the retrograde solubility of gases).

The result is that minerals in igneous rock weather in roughly the same order in which they were originally formed (Bowen's Reaction Series).

A fresh surface of a mineral crystal exposes ions whose electrical charge attracts water molecules.

As cations are removed, silicon-oxygen and silicon-aluminium bonds become more susceptible to hydrolysis, freeing silicic acid and aluminium hydroxides to be leached away or to form clay minerals.

[43] Decaying remains of dead plants in soil may form organic acids which, when dissolved in water, cause chemical weathering.

[44] Chelating compounds, mostly low molecular weight organic acids, are capable of removing metal ions from bare rock surfaces, with aluminium and silicon being particularly susceptible.

[49] It was also recently evidenced that bacterial communities can impact mineral stability leading to the release of inorganic nutrients.

[52] Buildings made of any stone, brick or concrete are susceptible to the same weathering agents as any exposed rock surface.

[32] The resulting soil is depleted in calcium, sodium, and ferrous iron compared with the bedrock, and magnesium is reduced by 40% and silicon by 15%.

In tropical settings, it rapidly weathers to clay minerals, aluminium hydroxides, and titanium-enriched iron oxides.

Where leaching is continuous and intense, as in rain forests, the final weathering product is bauxite, the principal ore of aluminium.

Where rainfall is intense but seasonal, as in monsoon climates, the final weathering product is iron- and titanium-rich laterite.

For example, the Willwood Formation of Wyoming contains over 1,000 paleosol layers in a 770 meters (2,530 ft) section representing 3.5 million years of geologic time.

[60] Wood can be physically and chemically weathered by hydrolysis and other processes relevant to minerals and is highly susceptible to ultraviolet radiation from sunlight.