Terra sigillata

Terra sigillata as an archaeological term refers chiefly to a specific type of plain and decorated tableware made in Italy and in Gaul (France and the Rhineland) during the Roman Empire.

When applied to unfired clay surfaces, "terra sig" can be polished with a soft cloth or brush to achieve a shine ranging from a smooth silky lustre to a high gloss.

[4] Whereas Anthony King's definition, following the more usual practice among Roman pottery specialists, makes no mention of decoration, but states that terra sigillata is 'alternatively known as samian ware'.

[5][a] Nomenclature has to be established at an early stage of research into a subject, and antiquarians of the 18th and 19th centuries often used terms that we would not choose today, but as long as their meaning is clear and well-established, this does not matter, and detailed study of the history of the terminology is really a side-issue that is of academic interest only.

Careful observation of form and fabric is therefore usually enough for an archaeologist experienced in the study of sigillata to date and identify a broken sherd: a potter's stamp or moulded decoration provides even more precise evidence.

The classic guide by Oswald and Pryce, published in 1920[9] set out many of the principles, but the literature on the subject goes back into the 19th century, and is now extremely voluminous, including many monographs on specific regions, as well as excavation reports on important sites that have produced significant assemblages of sigillata wares, and articles in learned journals, some of which are dedicated to Roman pottery studies.

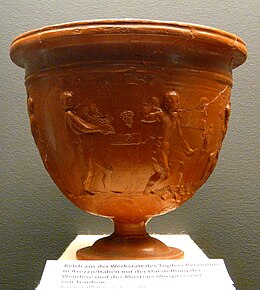

[10][11] The motifs and designs on the relief-decorated wares echo the general traditions of Graeco-Roman decorative arts, with depictions of deities, references to myths and legends, and popular themes such as hunting and erotic scenes.

At La Graufesenque in southern Gaul, documentary evidence in the form of lists or tallies apparently fired with single kiln-loads, giving potters' names and numbers of pots have long been known, and they suggest very large loads of 25,000–30,000 vessels.

It now appears as a result of this recent work that this is not the case and that the colour of the glossy slip is in fact due to no more than the crystal size of the minerals dispersed within the matrix glass.

[13] Arretine ware, in spite of its very distinctive appearance, was an integral part of the wider picture of fine ceramic tablewares in the Graeco-Roman world of the Hellenistic and early Roman period.

[15] The tradition of decorating entire vessels in low relief was also well established in Greece and Asia Minor by the time the Arretine industry began to expand in the middle of the 1st century BC, and examples were imported into Italy.

Relief-decorated cups, some in lead-glazed wares, were produced at several eastern centres, and undoubtedly played a part in the technical and stylistic evolution of decorated Arretine, but Megarian bowls, made chiefly in Greece and Asia Minor, are usually seen as the most direct inspiration.

27 BC – AD 14), this tableware, with its precise forms, shiny surface, and, on the decorated vessels, its visual introduction to Classical art and mythology, must have deeply impressed some inhabitants of the new northern provinces of the Empire.

The most recognisable decorated Arretine form is Dragendorff 11, a large, deep goblet on a high pedestal base, closely resembling some silver table vessels of the same period, such as the Warren Cup.

The deep form of the Dr.11 allowed the poinçons (stamps) used making the moulds of human and animal figures to be fairly large, often about 5–6 cm high, and the modelling is frequently very accomplished indeed, attracting the interest of modern art-historians as well as archaeologists.

Ateius, stamped their products, and the names of the factory-owners and of the workers within the factories, which often appear on completed bowls and on plain wares, have been extensively studied, as have the forms of the vessels, and the details of their dating and distribution.

[25] Research on Arretine ware has continued very actively throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, for example with the publication and revision of an inventory of the known potter's stamps ("Oxé-Comfort-Kenrick") and the development of a Conspectus of vessel forms, bringing earlier work on the respective topics up to date.

But many new shapes quickly evolved, and by the second half of the 1st century AD, when Italian sigillata was no longer influential, South Gaulish samian had created its own characteristic repertoire of forms.

The footring is low, and potters' stamps are usually bowl-maker's marks placed in the interior base, so that vessels made from the same, or parallel, moulds may bear different names.

The rim of the 29, small and upright in early examples of the form, but much deeper and more everted by the 70s of the 1st century, is finished with rouletted decoration,[b] and the relief-decorated surfaces necessarily fall into two narrow zones.

Small relief-decorated beakers such as forms Déchelette 67 and Knorr 78 were also made in South Gaul, as were occasional 'one-off' or very ambitious mould-made vessels, such as large thin-walled flagons and flasks.

Though it never achieved the extensive geographical distribution of the South Gaulish factories, in the provinces of Gaul and Britain, it was by far the most common type of fine tableware, plain and decorated, in use during the 2nd century AD.

Vessel-forms that had been made in South Gaul continued to be produced, though as the decades passed, they evolved and changed with the normal shifts of fashion, and some new shapes were created, such as the plain bowl with a horizontal flange below the rim, Dr.38.

Two standard 'plain' types made in considerable numbers in Central Gaul also included barbotine decoration, Dr.35 and 36, a matching cup and dish with a curved horizontal rim embellished with a stylised scroll of leaves in relief.

[36] The wares of Cinnamus, Paternus, Divixtus, Doeccus, Advocisus, Albucius and some others often included large, easily legible name-stamps incorporated into the decoration, clearly acting as brand-names or advertisements.

But the real strength of the Rheinzabern industry lay in its extensive production of good-quality samian cups, beakers, flagons and vases, many imaginatively decorated with barbotine designs or in the 'cut-glass' incised technique.

Small, localised attempts to make conventional relief-decorated samian ware included a brief and unsuccessful venture at Colchester in Britain, apparently initiated by potters from the East Gaulish factories at Sinzig, a centre that was itself an offshoot of the Trier workshops.

[42] In the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire, there had been several industries making fine red tablewares with smooth, glossy-slipped surfaces since about the middle of the 2nd century BC, well before the rise of the Italian sigillata workshops.

[48] In 1906 the German potter Karl Fischer re-invented the method of making terra sigillata of Roman quality and obtained patent protection for this procedure at the Kaiserliche Patentamt in Berlin.

[citation needed] In 1580, a miner named Adreas Berthold traveled around Germany selling Silesian terra sigillata made from a special clay dug from the hills outside the town of Striga, now Strzegom, Poland, and processed into small tablets.