Samnites

The Samnites (Oscan: Safineis) were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they formed a confederation consisting of four tribes: the Hirpini, Caudini, Caraceni, and Pentri.

Aside from relying on agriculture, the Samnites exported goods such as ceramics, bronze, iron, olives, wool, pottery, and terracottas.

[8] From Safinim, Sabinus, Sabellus and Samnis, an Indo-European root can be extracted, *sabh-, which becomes Sab- in Latino-Faliscan and Saf- in Osco-Umbrian: Sabini and *Safineis.

This date does not necessarily correspond to any historical or archaeological evidence; developing a synthetic view of the ethnology of proto-historic Italy is an incomplete and ongoing task.

Conjecturing that the -a- was altered from an -o- during some prehistoric residence in Illyria, he derives the names from an o-grade extension *swo-bho- of an extended e-grade *swe-bho- of the possessive adjective, *s(e)we-, of the reflexive pronoun, *se-, "oneself" (the source of English self).

[55] Samnites, who were some of the most prominent supporters of the Marians, were punished so severely that it was recorded, "some of their cities have now dwindled into villages, some indeed being entirely deserted."

[57][35] During the fifth and fourth centuries BC, an increasing population combined with trade links to other Italians contributed to further agricultural and urban development.

The city began as a major grain producer with a mill and a threshing floor, and later developed into the hub for all economic activity in the Biferno Valley.

Samnite currency developed in the late fifth and early fourth centuries BC, likely as a consequence of interaction with the Greeks, and war, which created a need for mercenaries.

Most loom weights used incised lines, dots, oval stamps, gem impressions, or imprints from metal signet rings to create patterns.

These Greek words may have served a variety of possibilities, such as instructing the weaver how to order the threads in the textile patterns, or they could also have marked the piece's quality.

[11][77] One example of a pottery stamp is:[15] Detfri (slave) of Herennis Sattis signed in planta pedis.Throughout the Iron Age Samnium was ruled by chieftains and aristocrats who used funerary displays to flaunt their wealth.

During the early third and fourth centuries, the Samnite political system developed into an organization focused on rural settlements led by magistrates.

[80] Despite these democratic institutions, Samnite society was still dominated by a small group of aristocratic families such as the Papii, Statii, Egnatii, and Staii.

This new system used phalanxes, hoplites, maniples, and cohorts made of 400 men, creating an army flexible enough to fight in mountainous terrain.

Livy mentions a legio linteata ("linen legion");[91] this unit used flamboyant equipment to differentiate itself from other Samnite warriors.

The second type utilized an edge to outline the discs, while the third used plates to depict the heads of religious figures such as Athena or demons.

Young adult women were typically buried with coils, pendants, beads, clothing, spindles, and fibulae similar to those worn by boys,[134] possibly meaning that femininity was tied to youth in Samnite culture.

Differences in jewelry between the graves of adolescent and young adult women could be a form of preventative healthcare; it may have been done to protect them in childbirth.

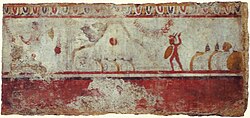

For example, hierarchy of scale, clothing demonstrating status, captions, episodic narratives, and depictions of history were all borrowed from other cultures.

Women wore long sleeveless peplum, caps, hats similar to a pileus, chitons, decorated belts, and chatelaine.

Another piece of art shows a Samnite woman wearing a hairnet beneath a cylindrical headdress with white and red stripes running across it.

Red, white, or black belts covered in motifs that were usually made by using hooks to fasten cloth or leather into holes were worn by both genders.

These were usually made from one piece of cloth and decorated with black or white motifs that were almost always placed on the sleeves, though rarely on the lower part of the tunic.

These clothes might have been designed to give a chameleon-like appearance Livy may have intended to invoke ideas of Aeneas, who once allied with a warrior named Astyr, who had multi-colored weapons and armor.

Roman and Greek authors such as Livy, Strabo, Horace, Athenaeus, and Silius Italicus mention that the Campanian aristocrats would host gladiator games during their banquets.

[5][29] Hillforts built with polygonal walling may have been either a common defensive fortification or a form of settlement that represented a transitional phase between a more rural society and a more urban one.

[60][165] Façades made of tuff, tabernae, peristyles, dentil cornices supported by cubic capitals, which are the upper part of a column, used figurines and were all located outside of the houses.

[169] One farmhouse found near Campobasso consists of a square module, which was likely a stable house, and a series of rooms with hearths centered around a courthouse.