Sampling bias

It results in a biased sample[1] of a population (or non-human factors) in which all individuals, or instances, were not equally likely to have been selected.

[11] A distinction, albeit not universally accepted, of sampling bias is that it undermines the external validity of a test (the ability of its results to be generalized to the entire population), while selection bias mainly addresses internal validity for differences or similarities found in the sample at hand.

Studies carefully selected from whole populations are showing that many conditions are much more common and usually much milder than formerly believed.

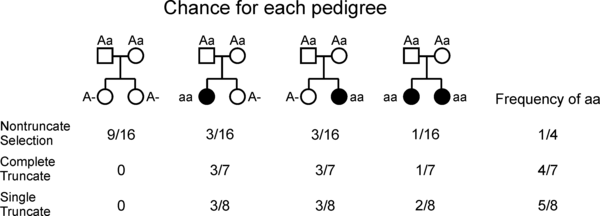

Following the laws of Mendelian inheritance, if the parents in a family do not have the characteristic, but carry the allele for it, they are carriers (e.g. a non-expressive heterozygote).

The problem arises because we can't tell which families have both parents as carriers (heterozygous) unless they have a child who exhibits the characteristic.

In statistical usage, bias merely represents a mathematical property, no matter if it is deliberate or unconscious or due to imperfections in the instruments used for observation.

Some have called this a 'demarcation bias' because the use of a ratio (division) instead of a difference (subtraction) removes the results of the analysis from science into pseudoscience (See Demarcation Problem).

The U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, for example, deliberately oversamples from minority populations in many of its nationwide surveys in order to gain sufficient precision for estimates within these groups.

Provided that certain conditions are met (chiefly that the weights are calculated and used correctly) these samples permit accurate estimation of population parameters.

In the early days of opinion polling, the American Literary Digest magazine collected over two million postal surveys and predicted that the Republican candidate in the U.S. presidential election, Alf Landon, would beat the incumbent president, Franklin Roosevelt, by a large margin.

The Literary Digest survey represented a sample collected from readers of the magazine, supplemented by records of registered automobile owners and telephone users.

On election night, the Chicago Tribune printed the headline DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN, which turned out to be mistaken.

In the morning the grinning president-elect, Harry S. Truman, was photographed holding a newspaper bearing this headline.

Survey research was then in its infancy, and few academics realized that a sample of telephone users was not representative of the general population.

(In many cities, the Bell System telephone directory contained the same names as the Social Register).