Samuel Chidley

Daniel and Katherine Chidley were denounced as separatists by the Puritan public preacher of Shrewsbury, Julines Herring,[5] and this separatism may account for their reluctance to have their children baptised at their parish church.

[8] This was part of protracted hostilities between the High Church incumbent, Peter Studley, and his Puritan parishioners in which both the separatists and the moderate Presbyterians around Herring were accused of absenting themselves from the Eucharist and setting up conventicles.

David Brown, a veteran of the group led by Duppa and the Chidleys reminisced about tearing a surplice as a deliberate act of iconoclasm one St Luke's Day (18 October) at Greenwich, a place made notorious in their eyes for the Catholic chapel that Queen Henrietta Maria had installed in her house there.

The Scottish Covenanters had defeated the king in the Bishops' Wars and when Parliament entered into negotiations for an alliance, pressed for a Presbyterian reformation of the Church of England.

[2] The Biblical texts she placed on the title page both attested her preference for thinking through the experience of the Judges and the early Israelite monarchy, tending to confirm the significance of Samuel's name.

The first recorded instance seems to have been in June 1645, when he, together with two other members, John Duppa and David Brown, took part in a conference with Henry Burton of St Matthew Friday Street.

The key tenet they wished to defend in the debate was that the former parish churches were to be shunned and demolished as were the "high places" of the Ancient Canaanite religion by the kings of Judah.

The separatist position was in direct contradiction to the concluding statement of the Directory for Public Worship, adopted by an act of parliament in January 1645 to replace the Book of Common Prayer.

[26] In August 1648 Samuel Chidley debated with John Goodwin, the minister of St. Stephen Coleman Street, who had attempted a compromise between a gathered church and a parish church: he used St Stephen's as a teaching and preaching base in this most turbulent and lively part of the capital, while administering communion only to the select group, not necessarily from the area, approved by himself and his elders.

With the key leaders, John Lilburne and Richard Overton in prison, Chidley and Prince were especially important in the latter part of 1647, as capable and literate proponents of the cause.

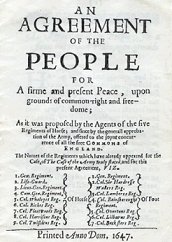

[32] During this period, the first Agreement of the People took shape among the Agitators, the representatives of the soldiers, setting out a series of demands that they considered would protect the gains made in the Civil War and constituting a rejection of the army commanders' Heads of Proposals.

With the inconclusive ending of the debates, Samuel Chidley was one of those who took forward the Agreement[9] as a propaganda document to a rendezvous of the army at Corkbush Field, near Ware, Hertfordshire, where the commanders hoped for a decision in favour of the Heads of Proposals and of Thomas Fairfax personally.

The resulting Corkbush Field mutiny of 15 November 1647 was suppressed mainly by the prompt action of Oliver Cromwell, who ordered the immediate execution by shooting of a single Leveller, Richard Arnold of Robert Lilburne's regiment.

[39] The petition also challenged Parliamentary sovereignty by asserting that "the power of this, and all future Representatives of this Nation, is inferior only to theirs who choose them,"[40] and proposing to exclude from political control "matters of religion and the ways of God's worship."

To rub salt in the wound, the House also deputed Sir John Evelyn to write a letter thanking Cromwell for the summary execution of Arnold and urging him to carry out further "condign and exemplary Punishment."

[9] The documents at the forefront of Leveller agitation at that time were John Lilburne's Earnest Petition,[42] which called for a greatly extended suffrage, election of magistrates and other constitutional innovations,[43] and The mournful cries of many thousand poor tradesmen, which drew attention to widespread economic distress.

Although committed to an austere and rigorous Puritan sect and a radical political movement, Samuel Chidley found opportunities to prosper as a businessman and administrator.

[2] Katherine Chidley continued her husband's business, probably with Samuel's help, and it was she who was named as payee for over £350 worth of stockings for the army involved the final phases of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland.

[50][51] In 1649, the year he became a freeman of the Haberdashers' Company, Samuel Chidley was appointed Register of Debentures,[9] a post he acquired allegedly with the assistance of David Brown.

The troops received, in lieu of pay, debentures that allowed them to purchase portions of the royal estates left owner-less by the execution of Charles I.

The necessary legislation for the sale of the royal family's property was passed on 11 July 1649,[53] acknowledging in its preface that Parliament was "engaged both in Honor and Justice to make due satisfaction unto all Officers and Soldiers for their Arrears,"[54] although Chidley's post had already been established on 22 June.

He was based in Worcester House,[9] then a prestigious address near St James Garlickhythe, used by the Worshipful Company of Fruiterers and with a notable view across the River Thames.

[61] Noting that the Biblical solution to the problem was enslavement for theft, Chidley suggested a period of forced labour to compensate the victim, as already practised in the Dutch Republic, mentioning plantation slavery or employment in the mines.

[57] However, Chidley launched a campaign in December 1652 for a more prompt settlement between the Rump Parliament and state creditors, who were offered repayment only if they "doubled", i.e. immediately advanced the identical sum again.

[65] In 1656 Chidley returned to an old theme, presenting to the Second Protectorate Parliament Thunder from the Throne of God Against the Temples of Idols, a denunciation of the "high places", packed with supporting Biblical texts and fiery rhetoric.

The book was then referred to a committee, which included Jephson and Colonel Shapcott, an MP who had complained to the previous parliament when he became the subject of a scurrilous publication.

[71] The following year Chidley issued a general diatribe addressed To his Highness the Lord Protector, and the Parliament of England, &c. Beginning with a ringing announcement of the brotherhood of all humans in the image of God,[72] he went on to bemoan the inactivity of Parliament: These lapses, he predictably announced, included a failure to abolish the death penalty for theft and leaving the public debt unpaid.

[74] This allowed him to unite both issues in a picture of a land where there was no support for the poor, who were excluded from the enclosed fields and orchards, justice was denied, lawyers prospered by lying, while beggars and thieves swarmed.

[75] He concluded by pointing out the responsibility for the state of the nation lay with Parliament, urging it to "unbinde, loosing the bnds of wickedness, undoing the heavy burdens, and letting the oppressed go free, and breaking every yoke."

A decade later, in 1662, he was in a house of two hearths in Chequer Alley in the Bishopsgate Ward,[79] part of the densely populated area[80] to the east of Coleman Street.