Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Coleridge had a turbulent career and personal life with a variety of highs and lows, but his public esteem grew after his death, and he became considered one of the most influential figures in English literature.

[9] After John Coleridge died in 1781, 8-year-old Samuel was sent to Christ's Hospital, a charity school which was founded in the 16th century in Greyfriars, London, where he remained throughout his childhood, studying and writing poetry.

I learnt from him, that Poetry, even that of the loftiest, and, seemingly, that of the wildest odes, had a logic of its own, as severe as that of science; and more difficult, because more subtle, more complex, and dependent on more, and more fugitive causes...In our own English compositions (at least for the last three years of our school education) he showed no mercy to phrase, metaphor, or image, unsupported by a sound sense, or where the same sense might have been conveyed with equal force and dignity in plainer words...In fancy I can almost hear him now, exclaiming Harp?

[15] In December 1793, he left the college and enlisted in the 15th (The King's) Light Dragoons using the false name "Silas Tomkyn Comberbache",[16] perhaps because of debt or because the girl that he loved, Mary Evans, had rejected him.

[citation needed] At Jesus College, Coleridge was introduced to political and theological ideas then considered radical, including those of the poet Robert Southey with whom he collaborated on the play The Fall of Robespierre.

In 1798, Coleridge and Wordsworth published a joint volume of poetry, Lyrical Ballads, which proved to be the starting point for the English romantic age.

I suppose you must have heard that his daughter, (Jane, on 15 April 1798) in a melancholy derangement, suffered herself to be swallowed up by the tide on the sea-coast between Sidmouth and Bere [sic] (Beer).

Coleridge later visited Hazlitt and his father at Wem but within a day or two of preaching he received a letter from Josiah Wedgwood II, who had offered to help him out of financial difficulties with an annuity of £150 (approximately £13,000 in today's money[24]) per year on condition he give up his ministerial career.

The figure has a wyvern at his feet, a reference to the Sockburn Worm slain by Sir John Conyers (and a possible source for Lewis Carroll's Jabberwocky).

[29] Coleridge's early intellectual debts, besides German idealists like Kant and critics like Lessing, were first to William Godwin's Political Justice, especially during his Pantisocratic period, and to David Hartley's Observations on Man, which is the source of the psychology which is found in Frost at Midnight.

In 1800, he returned to England and shortly thereafter settled with his family and friends in Greta Hall at Keswick in the Lake District of Cumberland to be near Grasmere, where Wordsworth had moved.

[30] His marital problems, nightmares, illnesses, increased opium dependency, tensions with Wordsworth, and a lack of confidence in his poetic powers fuelled the composition of Dejection: An Ode and an intensification of his philosophical studies.

From 1807 to 1808, Coleridge returned to Malta and then travelled in Sicily and Italy, in the hope that leaving Britain's damp climate would improve his health and thus enable him to reduce his consumption of opium.

[33] His opium addiction (he was using as much as two quarts of laudanum a week) now began to take over his life: he separated from his wife Sara in 1808, quarrelled with Wordsworth in 1810, lost part of his annuity in 1811, and put himself under the care of Dr. Daniel in 1814.

The Friend was an eclectic publication that drew upon every corner of Coleridge's remarkably diverse knowledge of law, philosophy, morals, politics, history, and literary criticism.

Much of Coleridge's reputation as a literary critic is founded on the lectures that he undertook in the winter of 1810–11, which were sponsored by the Philosophical Institution and given at Scot's Corporation Hall off Fetter Lane, Fleet Street.

As a result of these factors, Coleridge often failed to prepare anything but the loosest set of notes for his lectures and regularly entered into extremely long digressions which his audiences found difficult to follow.

In September 2007, Oxford University Press sparked a heated scholarly controversy by publishing an English translation of Goethe's work that purported to be Coleridge's long-lost masterpiece (the text in question first appeared anonymously in 1821).

He published other writings while he was living at the Gillman homes, notably the Lay Sermons of 1816 and 1817, Sibylline Leaves (1817), Hush (1820), Aids to Reflection (1825), and On the Constitution of the Church and State (1830).

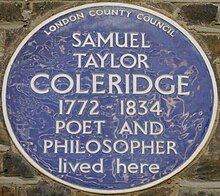

Coleridge died in Highgate, London on 25 July 1834 as a result of heart failure compounded by an unknown lung disorder, possibly linked to his use of opium.

Coleridge could see the red door of the then new St Michael's Church from his last residence across the green, where he lived with a doctor he had hoped might cure him (in a house owned by Kate Moss until 2022).

[48][4][49] A recent excavation revealed the coffins were not in the location most believed, the far corner of the crypt, but below a memorial slab in the nave inscribed with: "Beneath this stone lies the body of Samuel Taylor Coleridge".

"[57] The last ten lines of Frost at Midnight were chosen by Harper as the "best example of the peculiar kind of blank verse Coleridge had evolved, as natural-seeming as prose, but as exquisitely artistic as the most complicated sonnet.

"[58] The speaker of the poem is addressing his infant son, asleep by his side: Therefore all seasons shall be sweet to thee, Whether the summer clothe the general earth With greenness, or the redbreast sit and sing Betwixt the tufts of snow on the bare branch Of mossy apple-tree, while the nigh thatch Smokes in the sun-thaw; whether the eave-drops fall Heard only in the trances of the blast, Or if the secret ministry of frost Shall hang them up in silent icicles, Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.

"[54] In addition to his poetry, Coleridge also wrote influential pieces of literary criticism including Biographia Literaria, a collection of his thoughts and opinions on literature which he published in 1817.

[64] In Biographia Literaria and his poetry, symbols are not merely "objective correlatives" to Coleridge, but instruments for making the universe and personal experience intelligible and spiritually covalent.

To Coleridge, the "cinque spotted spider," making its way upstream "by fits and starts," [Biographia Literaria] is not merely a comment on the intermittent nature of creativity, imagination, or spiritual progress, but the journey and destination of his life.

Two legs of the spider represent the "me-not me" of thesis and antithesis, the idea that a thing cannot be itself and its opposite simultaneously, the basis of the clockwork Newtonian world view that Coleridge rejected.

He comments in his reviews: "Situations of torment, and images of naked horror, are easily conceived; and a writer in whose works they abound, deserves our gratitude almost equally with him who should drag us by way of sport through a military hospital, or force us to sit at the dissecting-table of a natural philosopher.

However, Coleridge used these elements in poems such as The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), Christabel and Kubla Khan (published in 1816, but known in manuscript form before then) and certainly influenced other poets and writers of the time.