Sanjna

Saranyu (or Saraṇyū) is the first name used for the goddess and is derived from the Sanskrit root sar, meaning "to flow" or "to run," which suggests associations with movement, speed, or impetuosity.

The imagery of flowing or running connects Saranyu to the idea of natural forces, perhaps even hinting at an ancient link with river goddesses.

Indologist Wendy Doniger explains that the change from Saranyu to Samjñā reflects the evolving philosophical concerns in Hindu mythology.

In Samjñā, the myth explores the nature of identity, as the character is literally and metaphorically a sign or image of herself, especially through her surrogate, Chhaya, who is her shadow or reflection.

Furthermore, both names carry linguistic significance: while "Samjñā" means "sign" or "image," "Sandhya" is linked to "twilight speech" in later Hindi poetry, which is marked by riddles, inversions, and paradoxes.

[5][7] In the Rig Veda (c. 1200-1000 BCE), Saranyu's story unfolds as a cryptic narrative, focusing on her marriage to Vivasvant, the Sun god, and the events that follow.

The story in the Rig Veda presents these events in a fragmented and riddle-like manner, with no explicit explanations for Saranyu's actions or the creation of her double.

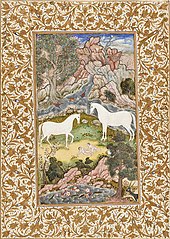

Their union as horses produces the Ashvins, who are conceived in an unconventional manner—Saranyu inhales the semen that had fallen on the ground, leading to the twins' birth.

[2] Wendy Doniger and other scholars have suggested that the cryptic nature of the Rig Veda's narrative about Saranyu is not accidental but a deliberate feature of Vedic literature.

These are enigmatic verses that present mythological events in riddle-like form, leaving the audience to decipher the underlying meanings and connections.

This approach reflects the Vedic method of storytelling, where stories were often concealed and revealed in parts, requiring interpretation by the reader or listener.

The deliberate withholding of explanations about key events—such as Saranyu's disappearance, the creation of her double, and the birth of the Ashvins—suggests that these verses are meant to provoke thought rather than provide straightforward answers.

According to Bloomfield, the text invites its audience to solve the riddle by connecting the clues offered, with Saranyu's name being the final piece of the puzzle.

Doniger highlights that Saranyu, whose name means "flowing" (possibly hinting at a river or a swift-moving force), leaves behind a mortal double, the savarna.

In early Vedic literature, divine figures like Saranyu often operate in ways that question agency—was her flight an act of autonomy, or was it imposed upon her by the gods or by circumstances?

This narrative suggests that she was an active agent in her own escape and in the creation of the savarna, which complicates the traditional portrayal of women in Vedic literature as passive or controlled by male figures.

By fleeing as a mare and being pursued as a stallion, Saranyu and Vivasvant transcend the normal boundaries of human and divine relationships, leading to the birth of the liminal Ashvins, who exist between mortal and immortal worlds.

Doniger points out that the concept of twinhood extends beyond simple sibling relationships in Vedic mythology; it symbolizes duality, opposites, and complementary forces, with Yama representing death and the Ashvins embodying healing and life.

This blending of divine and mortal realms in her offspring reflects a broader Vedic concern with the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth, as seen in the daily rise and fall of the sun—an event often associated with Vivasvant in later interpretations.

In this later narrative, Saranyu is renamed Samjna, while the surrogate she creates is no longer described as merely of-the-same-kind (savarna) but is instead depicted as her chhaya—her shadow or mirror image.

Vivasvant, sympathetic to his son's plight, cannot entirely revoke the curse but mitigates its effects by declaring that worms will consume part of Yama's foot, sparing him from complete loss.

This interpretation also ties into broader social meanings of varna in ancient texts, where it began to reflect both racial and class distinctions.

As her gaze flickers and darts about in fear, Samjna is further cursed to give birth to a daughter, Yamuna, who will become a river that flows in a similarly erratic manner.

Unable to further tolerate her husband's fiery energy, Samjna leaves behind her own personified shadow, named Chhaya, and goes to her father's house.

[2] In the Vishnu Purana, a similar legend is recited by sage Parashara, but here instead of Tvashtr, Samjna is identified as the daughter of Vishvakarman, the divine architect and craftsman.

Additionally, Samjna's departure is more explicitly linked to her desire to perform tapas (penance) in the forest to gain control over the Sun's heat.

[10][11] Vishvakarma reduces 1/8th of Surya's radiance and using it, he creates many celestial weapons including Vishnu's disc, Shiva's trident and Kartikeya's vel.

[13] The Skanda Purana identifies Samjna's mother as Rechana or Virochanā, the daughter of the pious daitya Prahlada and the wife of Tvashtr.

Additionally, it equates Samjna with Rajni and Prabha, who are mentioned as distinct wives of Surya in a few different texts, particularly those related to his iconography.