Alberto Santos-Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont was the sixth child of Henrique Dumont, an engineer who graduated from the Central School of Arts and Manufactures in Paris, and Francisca de Paula Santos.

"[29] Santos-Dumont would remember with nostalgia the times spent on his father's farm, where he enjoyed the greatest freedom: I lived a free life there, which was indispensable to form my temperament and taste for adventure.

He began building kites and small aeroplanes powered by a propeller driven by twisted rubber springs,[15]: 29 as he says in a commentary on the letter he received the day he won the Deutsch prize, recalling his childhood: "This letter brings back to me the happiest days of my life, when I exercised myself in making light aeroplanes with bits of straw, moved by screw propellers driven by springs of twisted rubber, or ephemeral silk-paper balloons."

[44]: 226 [O] At 24 years of age, Santos-Dumont left for France, where he hired professional aeronauts to teach him ballooning after reading the book Andrée – Au Pôle Nord en ballon.

[53]: 4 Santos-Dumont advocated for government investment in aviation development[U] and the importance of public opinion, something previously noted by Júlio César Ribeiro de Sousa [pt].

[13]: 308 Airships, powered aerostats, were first demonstrated and patented by the Brazilian priest Bartolomeu de Gusmão in 1709, and were flown by the Montgolfier Brothers in 1783,[53]: 3 but until the late 19th century had yet to be mastered, having been attempted by Henri Giffard,[45]: 360 [V] Charles Renard and Arthur Constantin Krebs in a flight with an electric motor in a closed circuit[W] in a project abandoned by the French Army, and by the Brazilian Júlio César Ribeiro de Sousa [pt], without success.

[42]: 21 A detail raised by Santos-Dumont refers to the definition of what would be heavier than air: in June 1902 he published an article in the North American Review arguing that his work on airships was about aviation, because hydrogen gas itself was not capable of taking off, and engine power was also needed.

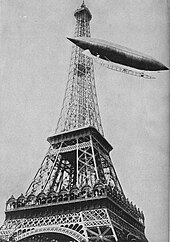

The regulations stipulated that an aircraft must be able to fly to the Eiffel Tower, round the monument, and return to the place of ascent in no more than thirty minutes, without stops, a total of 11 kilometres, under the eyes of a commission from the Aeroclub de France convened at least one day in advance.

On 19 September, before members of the International Congress of Aeronauts, he proved the effectiveness of an aerial propeller driven by an oil engine by flying repeatedly against the wind, even with a broken rudder, impressing the scientists present.

[15]: 131 On 8 May, trying for the prize again, he crashed his aircraft into the Hotel Trocadero;[20]: 11 the balloon exploded and was completely destroyed, but he escaped unscathed[15]: 134–138 and publicly tested the engine to show its reliability.

[53]: 5 After winning the Deutsch Prize, Santos-Dumont received letters from several countries, congratulating him;[15]: 177 [AP] magazines published lavish, richly illustrated editions to reproduce his image and perpetuate the achievement;[15]: 203 an Alexander Graham Bell interview in the New York Herald explored the reasons for Santos-Dumont's success, envy of other inventors, and the experiments that preceded him;[21]: 14 tributes were paid in France, Brazil, England, where the English Aero Club offered a banquet,[34]: 42 and several other countries.

The president of Brazil, Campos Sales sent him prize money of 100 million réis[AQ] following the proposal of Augusto Severo,[52]: 245 as well as a gold medal with his effigy and an allusion to Camões: "Through skies never sailed before";[36]: 202 [29] The Brazilian people were apathetic,[21]: 12 and in January 1902, Albert I, Prince of Monaco invited him to continue his experiments in the Principality.

He offered him a new hangar on the beach at La Condamine, and everything else Albert thought necessary for his comfort and safety,[15]: 180 which was accepted;[26]: 17 his success also inspired the creation of several biographies and influenced fictional characters, such as Tom Swift;[45]: 363 That April, Santos-Dumont travelled to the United States, where he visited Thomas Edison's laboratories in New York.

[34]: 43 He was received at the White House in Washington, DC, by President Theodore Roosevelt[78][71]: 260 and talked to U.S. Navy and Army officials about the possibility of using airships as a defence tool against submarines.

[13]: 317 Its success made clear the potential military use of the aircraft, especially for anti-submarine warfare, but its flights in the principality were interrupted by a crash in the Bay of Monaco on 14 February 1902.

[94] The second experiment was made on 8 June on the Seine: Gabriel Voisin went up in the hydroplane Archdeacon, towed by a speedboat piloted by Alphonse Tellier [fr], La Rapière.

[5][BJ] Excited, he decided to apply for the Archdeacon and Aeroclub of France awards the following day, his 33rd birthday, but was discouraged by Captain Ferdinand Ferber, another aviation enthusiast.

Like the water glider, the invention also consisted of a cellular biplane based on the structure created in 1893 by Australian researcher Lawrence Hargrave, which offered good support and rigidity.

On 13 September, the 14-bis made a 7 to 13-metre test flight with a 50 hp Antoinette engine,[26]: 18 [69]: 29 at 8:40 a.m,[33]: 41 which ended in an accident that damaged the propeller and landing gear,[43]: 74 but that was praised by La Nature magazine.

To compete for the French Aeroclub's prize, Santos-Dumont inserted two octagonal surfaces (rudimentary ailerons) between the wings for better steering control and created the Oiseau de Proie III.

"[104]: 52–53 [BN] Santos-Dumont even adopted the configuration proposed by the Wright brothers and placed the rudder at the front of the 14-bis, which he described as "the same as trying to shoot an arrow forward with the tail...".

[122][26]: 20 [BX] In his speech he showed concern about the efficiency of the aeroplane as a weapon of war, but advocated the creation of a squadron for coastal defence with the words, "Who knows when a European power will threaten an American state?

[126]} In the book O Que Eu Vi, O Que Nós Veremos, Santos-Dumont transcribed his letters of 1917 to the President of the Republic of Brazil, stressing the need to build military airfields for the Army and the Navy.

[110]: 55 Back in Brazil, they passed through Araxá, in Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and finally settled in Grand Hôtel La Plage, in Guarujá, in May 1932.

The heart is on display at the Air Force Museum in Campo dos Afonsos, Rio de Janeiro,[131][144]: 46 inside a sphere carried by Icarus, designed by Paulo da Rocha Gomide.

[69]: 32 During his career, Santos-Dumont's image was printed on products, his Panama hat and collar were copied, his balloons were modelled as toys, and confectioners made cakes shaped like airships.

[148] On the unveiling of the Saint-Cloud monument – a statue of Icarus[15]: 301–302 – one of his long-time friends, the cartoonist Georges Goursat (aka "Sem"), wrote the following for the magazine L'Illustration: This superb genius of athletic forms, with a grave profile, holding open in the tethers of his arms his wings, rudely wielded like two shields, nobly symbolizes the great work of Santos-Dumont: he would evoke in a very inaccurate way the simple, agile, laughing little big man that he is in reality.

[157][123]: 123 On 13 October 1997, the then President of the United States, Bill Clinton, visiting Brazil, gave a speech at the Itamaraty Palace, referring to Santos-Dumont as the "father of aviation".

[189]: 67 Cheniaux hypothesizes that Santos Dumont suffered from bipolar disorder or manic syndrome, with his latest bizarre inventions being able to demonstrate the "loss of critical ability".

[189]: 67 A letter written in 1931 by a doctor at the Orthez sanatorium to a friend of Santos Dumont describes him as 'suffering from anxious melancholy with delusions of self-blame, from imaginary guilt, and awaiting punishment', also identified as neurasthenia, an exhaustion of the central nervous system.