Sarasvati River

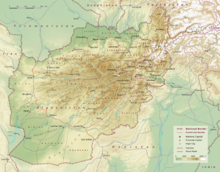

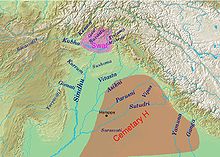

Since the late 19th century CE, numerous scholars have proposed to identify the Sarasvati with the Ghaggar-Hakra River system, which flows through modern-day northwestern-India and eastern-Pakistan, between the Yamuna and the Shutudri, and ends in the Thar desert.

10,000-8,000 years ago this channel was abandoned when the Sutlej diverted its course, leaving the Ghaggar-Hakra as a system of monsoon-fed rivers which did not reach the sea.

[16][17][f][13][12][14] In the words of Wilke and Moebus, the Sarasvati had been reduced to a "small, sorry trickle in the desert" by the time that the Vedic people migrated into north-west India.

[h][i] Sárasvatī is the feminine nominative singular form of the adjective sárasvat (which occurs in the Rigveda[29] as the name of the keeper of the celestial waters), derived from 'sáras' + 'vat', meaning 'having sáras-'.

Bridget and Raymond Allchin in The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan took the view that "The earliest Aryan homeland in India-Pakistan (Aryavarta or Brahmavarta) was in the Punjab and in the valleys of the Sarasvati and Drishadvati rivers in the time of the Rigveda.

"[48] According to the medieval commentator Uvata, the five tributaries of the Sarasvati were the Punjab rivers Drishadvati, Shutudri (Sutlej), Asikini (Chenab), Vipasha (Beas), Iravati (Ravi).

Wilke and Moebus note that the "historical river" Sarasvati was a "topographically tangible mythogeme", which was already reduced to a "small, sorry trickle in the desert", by the time of composition of the Hindu epics.

[18] According to the Mahabharata (3rd c. BCE - 3rd c. CE) the Sarasvati River dried up to a desert (at a place named Vinasana or Adarsana)[52][53] and joins the sea "impetuously".

[6][65][66] The belief of Sarasvati joining at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna originates from the Puranic scriptures and denotes the "powerful legacy" the Vedic river left after her disappearance.

[75][76][77] At least 10,000 years ago, well before the rise of the Harappan civilization, the sutlej diverted its course, leaving the Ghaggar-Hakra as a monsoon-fed river.

[11] Clift et al. (2012), using dating of zircon sand grains, have shown that subsurface river channels near the Indus Valley Civilisation sites in Cholistan immediately below the presumed Ghaggar-Hakra channel show sediment affinity not with the Ghagger-Hakra, but instead with the Beas River in the western sites and the Sutlej and the Yamuna in the eastern ones.

[88] Likewise, Dave et al. (2019) state that "[o]ur results disprove the proposed link between ancient settlements and large rivers from the Himalayas and indicate that the major palaeo-fluvial system traversing through this region ceased long before the establishment of the Harappan civilisation.

[109] According to Gregory Possehl, "Linguistic, archaeological, and historical data show that the Sarasvati of the Vedas is the modern Ghaggar or Hakra.

Prasad, "we [...] find a considerable body of opinions [sic] among the scholars, archaeologists and geologists, who hold that the Sarasvati originated in the Sivalik hills [...] and descended through Adi Badri, situated in the foothills of the Shivaliks, to the plains [...] and finally debouched herself into the Arabian sea at the Rann of Kutch.

Mukherjee notes that many historians and archaeologists, both Indian and foreign, concluded that the word "Sarasvati" (literally "being full of water") is not a noun, a specific "thing".

However, Mukherjee believes that "Sarasvati" is initially used by the Rigvedic people as an adjective to the Indus as a large river and later evolved into a "noun".

He also suggests that in the post-Vedic and Puranic tradition the "disappearance" of Sarasvati, which to refers to "[going] under [the] ground in the sands", was created as a complementary myth to explain the visible non-existence of the river.

[21] Wilke and Moebus suggest that the identification is problematic since the Ghaggar-Hakra river was already dried up at the time of the composition of the Vedas,[18] let alone the migration of the Vedic people into northern India.

The Avesta extols the Helmand in similar terms to those used in the Rigveda with respect to the Sarasvati: "The bountiful, glorious Haetumant swelling its white waves rolling down its copious flood".

This matches the Rigvedic description of the Sarasvati flowing to the samudra, which according to him at that time meant 'confluence', 'lake', 'heavenly lake', 'ocean'; the current meaning of 'terrestrial ocean' was not even felt in the Pali Canon.

[120] Danino notes that accepting the Rigveda accounts as a mighty river as factual descriptions, and dating the drying up late in the third millennium, are incompatible.

[120] According to Danino, this suggests that the Vedic people were present in northern India in the third millennium BCE,[121] a conclusion which is controversial amongst professional archaeologists.

Danino then states that if the "testimony of the Sarasvati is added to this, the simplest and most natural conclusion is that the Vedic culture was present in the region in the third millennium.

[28] Romila Thapar points out that an alleged equation of the Indus Valley civilization and the carriers of Vedic culture stays in stark contrast to not only linguistic, but also archeological evidence.

She notes that the essential characteristics of Indus valley urbanism, such as planned cities, complex fortifications, elaborate drainage systems, the use of mud and fire bricks, monumental buildings, extensive craft activity, are completely absent in the Rigveda.

Similarly the Rigveda lacks a conceptual familiarity with key aspects of organized urban life (e.g. non-kin labour, facets or items of an exchange system or complex weights and measures) and doesn't mention objects found in great numbers at Indus Valley civilization sites like terracotta figurines, sculptural representation of human bodies or seals.

[w][130][131] In 2015, Reuters reported that "members of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh know that proof of the physical existence of the Vedic river would bolster their concept of a golden age of Hindu Indian Subcontinent."

[133] Surveys and satellite photographs confirm that there was once a great river that rose in the Himalayas, entered the plains of Haryana, flowed through the Thar-Cholistan desert of Rajasthan and eastern Sindh (running roughly parallel to the Indus) and then reached the sea in the Rann of Kutchh in Gujarat.

[134] The government constituted Sarasvati Heritage Development Board (SHDB) had conducted a trial run on 30 July 2016 filling the river bed with 100 cusecs of water which was pumped into a dug-up channel from tubewells at Uncha Chandna village in Yamunanagar.

"[136] The Sarasvati revival project seeks to build channels and dams along the route of the lost river, and develop it as a tourist and pilgrimage circuit.

1 = ancient river

2 = today's river

3 = today's Thar desert

4 = ancient shore

5 = today's shore

6 = today's town

7 = dried-up Harappan Hakra course, and pre-Harappan Sutlej paleochannels ( Clift et al. (2012) ).

1 = ancient river

2 = today's river

3 = today's Thar desert

4 = ancient shore

5 = today's shore

6 = today's town

7 = dried-up Harappan Hakkra course, and pre-Harappan Sutlej paleochannels ( Clift et al. (2012) )