Sator Square

[1][2][6] There are many other less-supported academic origin theories, such as a Pythagorean or Stoic puzzle, a Gnostic or Orphic or Italian pagan amulet, a cryptic Mithraic or Semitic numerology charm, or that it was simply a device for working out wind directions.

[1] The square has long associations with magical powers throughout its history (and even up to the 19th century in North and South America), including a perceived ability to extinguish fires, particularly in Germany.

[1][11] The existence of the square was long recognized from early medieval times, and various examples have been found in Europe, Asia Minor, North Africa (in mainly Coptic settlements), and the Americas.

[1][14] Haverfield was ultimately proved right by the 1931-32 excavations at Dura-Europos in Syria that uncovered three separate Sator square inscriptions, all in ROTAS-form, on the interior walls of a Roman military office (and a fourth a year later) that were dated from circa AD 200.

[1][15] Five years later in 1936, Italian archaeologist Matteo Della Corte [it] discovered a Sator square, also in ROTAS-form, inscribed on a column in the Palestra Grande [it] (the gymnasium) near the Amphitheatre of Pompeii (CIL IV 8623).

[16] This discovery led Della Corte to reexamine a fragment of a square, again also in ROTAS-form, that he had made in 1925 at the house of Publius Paquius Proculus, also at Pompeii (CIL IV 8123).

[19] Some academics, such as French historian Jules Quicherat,[10] believe the square should be read in a boustrophedon style (i.e. in alternating directions).

[1][5] British academic Duncan Fishwick observes that the translation from the boustrophedon approach fails when applied to a ROTAS-form square;[10] however, Belgian scholar Paul Grosjean reversed the boustrophedon rule on the ROTAS-form (i.e. starting on the right-hand side instead of the left) to get SAT ORARE POTEN, which loosely translates into the Jewish call to prayer, "are you able to pray enough?".

[1] J. Gwyn Griffiths contended that the term AREPO came, via Alexandria, from the attested Egyptian name "Hr-Hp" (ḥr ḥp), which he took to mean "the face of Apis".

[6][4][5] In 1938, British classical historian Donald Atkinson said the square occupied the "mysterious region where religion, superstition, and magic meet, where words, numbers, and letters are believed, if properly combined, to exert power over the processes of nature ...".

[1] These are likely derived from even earlier Coptic Christian works that also ascribe the wounds of Christ and the nails of the cross with names that resemble the five words from the square.

[1][14] During 1924 to 1926, three people separately discovered,[d] or rediscovered, that the square could be used to write the name of the Lord's Prayer, the "Paternoster", twice and intersecting in a cross-form (see image opposite).

[10] At the time of this discovery, the earliest known Sator square was from the fourth century,[b][1] further supporting the dating of the Christian symbolism inherent in the Paternoster theory.

The lack of any disturbance to the volcanic deposits at the palestra, however, meant that this was unlikely,[10][14][15] and the Paternoster theory as a proof of Christian origination lost much of its academic support.

[1][6][23] Italian historian Arsenio Frugoni found it written in the margin of the Carme delle scolte modenesi beside the Roma-Amor palindrome,[1] and Italian classicist Margherita Guarducci noted it was similar to the ROMA OLIM MILO AMOR two-dimensional acrostic word puzzle that was also found at Pompeii (see Wiktionary for details on the Pompeiian graffito), and at Ostia and Bolonia.

[1] Similarly, another ROTAS-form square scratched into a Roman-era wall in the basement of the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, was found alongside the Roma-Amor, and the Roma-Summus-Amor, palindromes.

[10] American classical epigraphist Rebecca Benefiel, noted that by 2012, Pompeii had yielded more than 13,000 separate inscriptions and that the house of Publius Paquius Proculus (where a square was found) had more than 70 pieces of graffiti alone.

[10] Fishwick, and others, consider the key failing of the Roman puzzle theory of origin is the lack of any explanation as to why the square would later become so strongly associated with Christianity, and with being a medieval charm.

[28][29] Fishwick concludes that the translations of the words ROTAS OPERA TENET AREPO SATOR are irrelevant, except to the extent that they make some sense and thereby hide a Jewish cryptic charm, and to require them to mean more is "to expect the impossible".

By the end of the Middle Ages, the "prophylactic magic" of the square was firmly established in the superstition of Italy, Serbia, Germany, and Iceland, and eventually even crossed to North America".

[1] An edict in 1743 by Duke Ernest Auguste of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach required all settlements to make Sator square disks to combat fires.

Jean du Choul describes a case where a person from Lyon recovered from insanity after eating three crusts of bread inscribed with the square.

[10] Scholars have found medieval Sator-based charms, remedies, and cures, for a diverse range of applications from childbirth, to toothaches, to love potions, to ways of warding off evil spells, and even to determine whether someone was a witch.

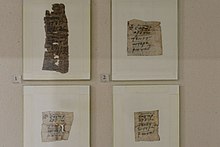

[1] The Sator square features in eighteenth-century books on Pow-wow folk medicine of the Pennsylvania Dutch, such as The Long Lost Friend (see image).