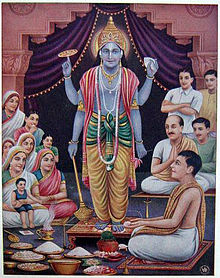

Satyanarayana Puja

Satya Chandra Mitra rejects these arguments, stating there is no historical evidence of anyone named Mansur Hāllāj and that Hindus have never appropriated foreign saints into their own worship.

Mitra, relying on the authenticity of the antiquity of the Purāṇas, states that its inclusion in the Revā Khaṇḍa is solid proof of the older origins of Satyanārāyaṇa worship.

The instructions for the Satya-nārāyaṇa-vrata-kathā are found the Revā Khaṇḍa of the Skanda Purāṇa which he states is a "modern work".

Once a Niṣādha or Bhilla wood carrier reached Kāśī where he saw the worship of Satyanārāyaṇa being performed.

The wood carrier learned the manner of Satyanārāyaṇa worship from Śatānanda, and returning to his home he performed the appropriate rites and the Bhillas achieved wealth and happiness.

Kalāvatī eventually properly performed the Satyanārāyaṇa rite, upon which Nārāyaṇa himself appeared to the king in a dream in the form of a Brahmin and orderd him to let Lakṣapati and Śaṅkhapati be free.

However, in her excitement to see her father, Lilāvatī rush out of the house leaving the Satyanārāyaṇa rite incomplete, leading to the ship her husband was on to sink.

[9][10] Roy states that the mention of Satya-nārāyan in the Skanda Purāṇa is an interpolation written in order to dislodge the worship of Satya-pir.

He quotes several Muslim writers that were compiled in the Bānglā Sāhityer Itihās that use phrases such as "Satya-pir-narayan" or "Pir-narayan" or call Satya Pir identical to the Hindu Trimurti.

The Bengali Skanda Purāṇa also adds a story at the end in which a king named Vaṁsadvaja arrogantly refuses to worship Satyanārāyaṇa and thus falls into misfortune until his repentance.

Sarma regards Satyanārāyaṇa as a Sanskritization of the Islamic saint Satya Pīr who was worshipped by Muslims and Hindus with śinni.

He notes the Bengali tales or vrata kathās which consider Satyanārāyaṇa and Satya Pīr to be identical, and states the worship of the deity originated in Bengal before spreading throughout northern India.

The Katha states how the deity Narayana vows to aid his devotees during Kali Yuga, the last of the four ages in Hindu cosmology, in particular the performers and attendees of the Satyanarayana Puja.