Sayf al-Dawla

Sayf al-Dawla's final years were marked by military defeats, his own growing disability as a result of disease, and a decline in his authority that led to revolts by some of his closest lieutenants.

Sayf al-Dawla's court at Aleppo was the centre of a vibrant cultural life, and the literary cycle he gathered around him, including the great al-Mutanabbi, helped ensure his fame for posterity.

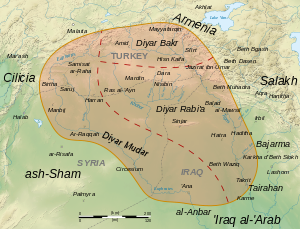

He raised troops for the caliph among the Taghlib in exchange for tax remissions, and established a commanding influence in the Jazira by acting as a mediator between the Abbasid authorities and the Arab and Kurdish population.

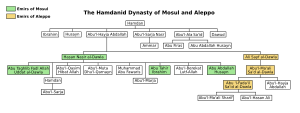

[2][10] Husayn was a successful general, distinguishing himself against Kharijite rebels in the Jazira and the Tulunids of Egypt, but was disgraced after supporting the failed usurpation of the throne by the Abbasid prince Ibn al-Mu'tazz in 908.

Enjoying firm relations with the powerful Abbasid commander-in-chief Mu'nis al-Muzaffar, he later played a leading role in the short-lived usurpation of al-Qahir against Caliph al-Muqtadir in 929, and was killed during its suppression.

Ali was successful in preventing Ibn Ja'far from receiving the assistance of his Armenian allies, and also secured control over the northern parts of the neighbouring province of Diyar Mudar after subduing the Bedouin (nomadic) Qaysi tribes of the region around Saruj.

[16] Ibn Ra'iq's position was anything but secure, however, and soon a convoluted struggle for control of the office of amir al-umara, and the Caliphate with it, broke out among the local rulers and the Turkic military chiefs, which ended in 946 with the victory of the Buyids.

[17] Al-Hasan initially supported Ibn Ra'iq, but in 942 he had him assassinated and secured for himself the post of amir al-umara, receiving the honorific (laqab) of Nasir al-Dawla ('Defender of the Dynasty'), by which he is best known to posterity.

As Thierry Bianquis writes, following the failure of his brother's designs in Iraq, Sayf al-Dawla's turn to Syria was "born of resentment when, having returned to Nasibin, he found himself under-employed and badly paid".

[24] He gained the support of the local Bedouin tribe of Banu Kilab, and even the Kilabi governor installed by al-Ikhshid in Aleppo, Abu'l-Fath Uthman ibn Sa'id al-Kilabi, who accompanied the Hamdanid in his unopposed entrance into the city on 29 October 944.

Nevertheless, in October the two sides came to an agreement, broadly on the lines of al-Ikhshid's earlier proposal: the Egyptian ruler acknowledged Hamdanid control over northern Syria, and even consented to sending an annual tribute in exchange for Sayf al-Dawla's renunciation of all claims on Damascus.

Not only would Egypt, threatened by this time by the Fatimid Caliphate in the west, be spared the cost of maintaining a large army in these distant lands, but the Hamdanid emirate would also fulfill the useful role of a buffer state against incursions both from Iraq and from Byzantium.

[36] Sayf al-Dawla benefitted from the fact that he was an ethnic Arab, unlike most of the contemporary rulers in the Islamic Middle East, who were Turkic or Iranian warlords who had risen from the ranks of the military slaves (ghilman).

[36] Finally, in spring 955 a major rebellion broke out in the region of Qinnasrin and Sabkhat al-Jabbul, which involved all tribes, both Bedouin and sedentary, including the Hamdanids' close allies, the Kilab.

Sayf al-Dawla was able to resolve the situation quickly, initiating a ruthless campaign of swift repression that included driving the tribes into the desert to die or capitulate, coupled with diplomacy that played on the divisions among the tribesmen.

Thus the Kilab were offered peace and a return to their favoured status, and were given more lands at the expense of the Kalb, who were driven from their abodes along with the Tayy, and fled south to settle in the plains north of Damascus and the Golan Heights, respectively.

The onset of decline in the Abbasid Caliphate after the Anarchy at Samarra was followed by the Battle of Lalakaon in 863, which had broken the power of the border emirate of Malatya and marked the beginning of the gradual Byzantine encroachment on the Arab borderlands.

[42][43] Finally, after 927, peace on their Balkan frontier enabled the Byzantines, under John Kourkouas, to turn their forces east and begin a series of campaigns that culminated in the fall and annexation of Malatya in 934, an event which sent shock-waves among the Muslim world.

[48][49] In Kennedy's assessment, "compared with the inaction or indifference of other Muslim rulers, it is not surprising that Sayf al-Dawla's popular reputation remained high; he was the one man who attempted to defend the Faith, the essential hero of the time".

[51][52][53] His most important campaign in these early years was in 939–940, when he invaded southwestern Armenia and secured a pledge of allegiance and the surrender of a few fortresses from the local princes—the Muslim Kaysites of Manzikert and the Christian Bagratids of Taron and Gagik Artsruni of Vaspurakan—who had begun defecting to Byzantium, before turning west and raiding Byzantine territory up to Koloneia.

[61] Finally, Sayf al-Dawla's origin in the Jazira also affected his strategic outlook, and was probably responsible for his failure to construct a fleet, or to pay any attention at all to the Mediterranean, in stark contrast to most Syria-based polities in history.

In the next year, Sayf al-Dawla led a large force into Byzantine territory, ravaging the themes of Lykandos and Charsianon, but on his return he was ambushed by Leo Phokas in a mountain pass.

[72] In 963, the Byzantines remained quiet as Nikephoros was scheming to ascend the imperial throne,[77] but Sayf al-Dawla suffered the loss of his sister, Khawla Sitt al-Nas, and was troubled by the onset of hemiplegia as well as worsening intestinal and urinary disorders, which henceforth confined him to a litter.

[72] The disease limited Sayf al-Dawla's ability to intervene personally in the affairs of his state; he soon abandoned Aleppo to the charge of his chamberlain, Qarquya, and spent most of his final years in Mayyafariqin, leaving his senior ghilman to carry the burden of warfare against the Byzantines and the rebellions that sprang up in his domains.

The Hamdanid ruler fled to the safety of the fortress of Shayzar while the Byzantines raided the Jazira, before turning on northern Syria, where they launched attacks on Manbij, Aleppo and even Antioch, whose newly appointed governor, Taki al-Din Muhammad ibn Musa, went over to them with the city's treasury.

Transformed into a vassal state tributary to Byzantium by the 969 Treaty of Safar, it became a bone of contention between the Byzantines and the new power of the Middle East, the Fatimid Caliphate, that had recently conquered Egypt.

[93] During his nine years at Aleppo, al-Mutanabbi wrote 22 major panegyrics to Sayf al-Dawla,[94] which, according to the Arabist Margaret Larkin, "demonstrated a measure of real affection mixed with the conventional praise of premodern Arabic poetry.

"[93] The celebrated historian and poet, Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, was also part of the Hamdanid court, and dedicated his major encyclopedia of poetry and songs, Kitab al-Aghani, to Sayf al-Dawla.

[87] Though fiscal and military affairs were centralized in the two capitals of Aleppo and Mayyafariqin, local government was based on fortified settlements, which were entrusted by Sayf al-Dawla to relatives or close associates.

[87] According to Kennedy "even the capital of Aleppo seems to have been more prosperous under the following Mirdasid dynasty than under the Hamdanids",[102] and Bianquis suggests that Sayf al-Dawla's wars and economic policies both contributed to a permanent alteration in the landscape of the regions they ruled: "by destroying orchards and peri-urban market gardens, by enfeebling the once vibrant polyculture and by depopulating the sedentarised steppe terrain of the frontiers, the Hamdanids contributed to the erosion of the deforested land and to the seizure by semi-nomadic tribes of the agricultural lands of these regions in the 11th century".