Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow has been designated an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports populations of wintering velvet scoters, horned grebes, common loons, European shags and Eurasian curlews, as well as breeding black guillemots.

According to the latter, King Haakon IV of Norway anchored his fleet, including the flagship Kroussden that could carry nearly 300 men, on 5 August 1263 at St Margaret's Hope, where he saw an eclipse of the sun before he sailed south to the Battle of Largs.

En route back to Norway Haakon anchored some of his fleet in Scapa Flow for the winter, but he died that December while staying at the Bishop's Palace in Kirkwall.

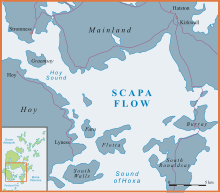

[4] In the 15th century towards the end of Norse rule in Orkney, the islands were run by the jarls from large manor farms, some of which were at Burray, Burwick, Paplay, Hoy, and Cairston (near Stromness) to guard the entrances to the Flow.

[5] In 1650 during the wars of the Three Kingdoms, the Royalist general James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, moored his ship, the Herderinnan, in Scapa Flow, in preparation for his attempt to raise a rebellion in Scotland.

[6] John Rushworth Jellicoe, admiral of the Grand Fleet, was perpetually nervous about the possibility of submarine or destroyer attacks on Scapa Flow.

Whilst the fleet spent almost the first year of the war patrolling the west coast of the British Isles, their base at Scapa was defensively reinforced, beginning with over sixty blockships sunk in the many entrance channels between the southern islands to enable the use of submarine nets and booms.

[6] Two attempts to enter the harbour were made by German U-boats during the war and neither was successful: After the Battle of Jutland, the German High Seas Fleet rarely ventured out of its bases at Wilhelmshaven and Kiel and in the last two years of the war the British fleet was considered to have such a commanding superiority of the seas that some components moved south to the first-class dockyard at Rosyth.

On 21 June 1919, after seven months of waiting, German Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter made the decision to scuttle the fleet because the negotiation period for the treaty had lapsed with no word of a settlement.

The Royal Navy managed to beach the battleship Baden, the light cruisers Emden, Nürnberg, and Frankfurt and 18 destroyers whereas 53 ships, the vast bulk of the High Seas Fleet, were sunk.

These ships posed a severe hazard to navigation; small boats, trawlers, and drifters regularly became snagged on them with the rise and fall of the tides.

In 1922, the Admiralty invited tenders from interested parties for the salvage of the sunken ships, although at the time few believed that it would be possible to raise the deeper wrecks.

First the relatively small destroyers were winched to the surface using pontoons and floating docks to be sold for scrap to help finance the operation, then the bigger battleships and battlecruisers were lifted, by sealing the multiple holes in the wrecks, and welding to the hulls long steel tubes which protruded above the water, for use as airlocks.

At one stage, during the General Strike of 1926, the salvage operation was about to grind to a halt due to a lack of coal to feed the many boilers for the water pumps and generators.

Cox ordered that the abundant fuel bunkers of the sunken (but only partly submerged) battlecruiser Seydlitz be broken into to extract the coal with mechanical grabs, allowing work to continue.

The last, the massive Derfflinger, was raised from a record depth of 45 metres just before work was suspended with the start of the Second World War, before being towed to Rosyth where it was broken up in 1946.

[8] Primarily because of its great distance from German airfields, Scapa Flow was again selected as the main British naval base during the Second World War.

The attack badly damaged an old base ship, the decommissioned battleship HMS Iron Duke, which was then beached at Ore Bay by a tug.

[15] New blockships were sunk, booms and mines were placed over the main entrances, coast defence and anti-aircraft batteries were installed at crucial points, and Winston Churchill ordered the construction of a series of causeways to block the eastern approaches to Scapa Flow; they were built by Italian prisoners of war held in Orkney, who also built the Italian Chapel.

The Visitor Centre occupies a converted naval fuel pumping station and storage tank and next to it is a round stone-built battery emplacement and artillery gun as well as other decommissioned arsenal.