Schenck v. United States

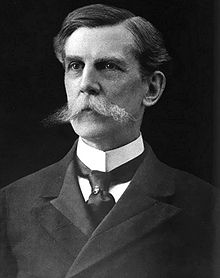

A unanimous Supreme Court, in an opinion by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., concluded that Charles Schenck and other defendants, who distributed flyers to draft-age men urging resistance to induction, could be convicted of an attempt to obstruct the draft, a criminal offense.

In this case, Holmes said, "the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent."

In 1969, Schenck was largely overturned by Brandenburg v. Ohio, which limited the scope of speech that the government may ban to that directed to and likely to incite imminent lawless action (e.g. a riot).

The United States' entry into the First World War had caused deep divisions in society and was vigorously opposed, especially by socialists, pacifists, isolationists, and those who had ties to Germany.

In the first case arising from this campaign to come before the Court—Baltzer v. United States, 248 U.S. 593 (1918)—South Dakota farmers had signed a petition criticizing their governor's administration of the draft, threatening him with defeat at the polls.

Schenck alone accordingly is often cited as the source of this legal standard, and some scholars have suggested that Holmes changed his mind and offered a different view in his equally famous dissent in Abrams v. United States.

They relied heavily on the text of the First Amendment, and their claim that the Espionage Act of 1917 had what today one would call a "chilling effect" on free discussion of the war effort.

The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.

A unanimous Court in a brief per curiam opinion in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), abandoned the disfavored language while seemingly applying the reasoning of Schenck to reverse the conviction of a Ku Klux Klan member prosecuted for giving an inflammatory speech.

The Court said that speech could be prosecuted only when it posed a danger of "imminent lawless action," a formulation that is sometimes said to reflect Holmes' reasoning as more fully explicated in his Abrams dissent, rather than the common law of attempts explained in Schenck.