Schlieffen Plan

Moltke wrote later, The days are gone by when, for dynastical ends, small armies of professional soldiers went to war to conquer a city, or a province, and then sought winter quarters or made peace.

The quick victories of 1870 led Moltke to hope that he had been mistaken but by December, he planned an Exterminationskrieg against the French population by taking the war into the south, once the size of the Prussian Army had been increased by another 100 battalions of reservists.

Moltke intended to destroy or capture the remaining resources which the French possessed, against the protests of the German civilian authorities, who after the fall of Paris, negotiated a quick end to the war.

Goltz maintained the theme in other publications up to 1914, notably in Das Volk in Waffen (The People in Arms, 1883) and used his position as a corps commander from 1902 to 1907 to implement his ideas, particularly in improving the training of Reserve officers and creating a unified youth organisation, the Jungdeutschlandbund (Young Germany League) to prepare teenagers for military service.

According to Ritter (1969) the contingency plans from 1872 to 1890 were his attempts to resolve the problems caused by international developments, by adopting a strategy of the defensive, after an opening tactical offensive, to weaken the opponent, a change from Vernichtungsstrategie to Ermattungsstrategie.

[11] In February 1891, Schlieffen was appointed to the post of Chief of the Großer Generalstab (Great General Staff), the professional head of the Kaiserheer (Deutsches Heer [German Army]).

[15] Schlieffen continued the practice of staff rides (Stabs-Reise) tours of territory where military operations might take place and war games, to teach techniques to command a mass conscript army.

In the strategic circumstances of 1905, with the Russian army and the Tsarist state in turmoil after the defeat in Manchuria, the French would not risk open warfare; the Germans would have to force them out of the border fortress zone.

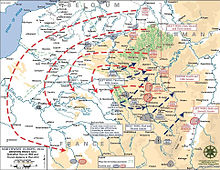

In Aufmarsch I, Germany would have to attack to win such a war, which entailed all of the German army being deployed on the German–Belgian border to invade France through the southern Dutch province of Limburg, Belgium and Luxembourg.

[21] The Russian reforms cut mobilisation time by half compared with 1906 and French loans were spent on railway building; German military intelligence thought that a programme due to begin in 1912 would lead to 6,200 mi (10,000 km) of new track by 1922.

Aufmarsch I Ost became a secondary deployment plan, as it was feared a French invasion force could be too well established to be driven from Germany or at least inflict greater losses on the Germans, if not defeated sooner.

The attacks of the French forces in southern Belgium and Luxembourg were conducted with negligible reconnaissance or artillery support and were bloodily repulsed, without preventing the westward manoeuvre of the northern German armies.

Theodor Jochim, the first head of the Reichsarchiv section for collecting documents, wrote that ... the events of the war, strategy and tactics can only be considered from a neutral, purely objective perspective which weighs things dispassionately and is independent of any ideology.

[37]The Reichsarchiv historians produced Der Weltkrieg, a narrative history (also known as the Weltkriegwerk) in fourteen volumes published from 1925 to 1944, which became the only source written with free access to the German documentary records of the war.

The consumption of food and ammunition at times and places are unknown, as are the quantity and loading of trains moving through Belgium, the state of repair of railway stations and data about the supplies which reached the front-line troops.

[49] Schlieffen was realistic and the plan reflected mathematical and geographical reality; expecting the French to refrain from advancing from the frontier and the German armies to fight great battles in the hinterland was found to be wishful thinking.

Schlieffen pored over maps of Flanders and northern France, to find a route by which the right wing of the German armies could move swiftly enough to arrive within six weeks, after which the Russians would have overrun the small force guarding the eastern approaches of Berlin.

[50] In the 1990s, after the dissolution of the German Democratic Republic, it was discovered that some Great General Staff records had survived the Potsdam bombing in 1945 and been confiscated by Soviet Military Administration in Germany authorities.

A lesser error was that the plan modelled the decisive defeat of France in one campaign of fewer than forty days and that Moltke the Younger foolishly weakened the attack, by being over-cautious and strengthening the defensive forces in Alsace-Lorraine.

Schlieffen wrote that the Germans must "wait for the enemy to emerge from behind his defensive ramparts" and intended to defeat the French army by a counter-offensive, tested in the general staff ride west of 1901.

[67][b] Holmes supported Zuber in his analysis that Schlieffen had demonstrated in his thought-experiment and in Aufmarsch I West, that 48+1⁄2 corps (1.36 million front-line troops) was the minimum force necessary to win a decisive battle against France or to take strategically important territory.

Humphries and Maker wrote that the interpretation of strategy put forward by Delbrück had implications about war planning and began a public debate, in which the German military establishment defended its commitment to Vernichtunsstrategie.

[71] Some of the writers of Die Grenzschlachten im Westen (The Frontier Battles in the West [1925]), the first volume of Der Weltkrieg, had already published memoirs and analyses of the war, in which they tried to explain why the plan failed in terms that confirmed its validity.

[39] Under these circumstances, the objectivity of the volume can be questioned as an instalment of the "battle of the memoirs", despite the claim in the foreword written by Foerster, that the Reichsarchiv would show the war as it actually happened (wie es eigentlich gewesen), in the tradition of Leopold von Ranke.

Universal military service enabled a state to exploit its human and productive resources to the full but also limited the causes for which a war could be fought; Social Darwinist rhetoric made the likelihood of surrender remote.

Major-General Ernst Köpke, the Generalquartiermeister (Quartermaster General) of the German army in 1895, wrote that an invasion of France past Nancy would turn into siege warfare with no quick and decisive victory.

[77] In 2006 the Center for Military History and Social Sciences of the Bundeswehr) published a collection of essays derived from a conference in 2004 held at Potsdam to discuss Terry Zuber's conclusion that there was no Schlieffen Plan.

In the Introduction to the volume, Hans Ehlert, Michael Epkenhans and Gerhard Gross wrote that Zuber's conclusion that the plan was a myth was a surprise, because many German generals had recorded at the time that the campaign in August and September had been based on Schlieffen.

Robert Foley described the substantial changes in Germany's strategic circumstances between 1905 and 1914 which compelled German planners to prepare for a quick one-front war which could only be fought against France, the evidence for which lay in Schlieffen's staff rides, of which Zuber had taken too little account.

[80] Dieter Storz wrote that plans and reality rarely match and that the extant Bavarian records bear out the basis of Schlieffen's thinking, that the French armies were to be outflanked by the right wing.